Kimmi Carlos, a middle school language arts teacher, and her husband Ryan, a Los Angeles firefighter, are the exception to the rule when it comes to infertility. After successfully giving birth to twins through in vitro fertilization (IVF) in their late 20s, the couple got pregnant naturally with their third child slightly over a year later.

After that unexpected pregnancy, a surplus of embryos remaining from the IVF cycle left the Carlos family with a new challenge. They had to weigh the emotional impact of donating embryos to a woman who would give birth to and raise a child who's genetically theirs.

And they were not necessarily prepared to make that kind of choice.

"When you're going through IVF, one thing that you're not really prepared for is the amount of extra embryos that you might have," Kimmi says. "The majority of people don't have a ton. They have what they need. So it's more common to have few than it is to have an abundance."

"The concern when you are choosing how many embryos to put inside of you is more the multiple pregnancies. Doctors really discourage more than twins, and so the doctor will have those conversations with you," Kimmi says. "It's not about, 'What if you have this abundance of embryos, then what's your plan?' That's not really a conversation that you have or you think about because of the mindset that you're in."

But Kimmi and Ryan Carlos did have an abundance of embryos. They were left with 12 strong embryos after successfully getting pregnant with their now-5-year-old twins, one boy and one girl.

Because all of the embryos Kimmi and Ryan produced were strong, their doctor selected two at random for transferring back into Kimmi's uterus. That was hard for the Carlos family to wrap their minds around.

"I personally struggled, as I'd be pushing my twins on swings at the park, with why they got to be the lucky two, as much as I loved them, that had a chance at life," Kimmi says. I felt in my heart the rest of them deserved the same chance at life."

But Kimmi had a tough time with her initial pregnancy with the twins. She spent nearly 12 weeks on bed rest, and she knew that she didn't want to go through that again.

Then 14 months after their twins were born, Kimmi miraculously got pregnant naturally with their third and final child, a son who's now 3.

Kimmi says that getting pregnant naturally, against the odds with only one fallopian tube and having been diagnosed with Endometriosis helped show them that donating their embryos was meant to be.

Most people don't understand how that's possible, how can you do that, how can you have another child that you're not raising and you're not loving and all of that, and I don't know the why or how behind that," Kimmi says. "The only thing I can say is that the feeling inside of us that they deserved a chance at life that we weren't willing to give was stronger than our own selfish feelings of, 'Oh, we can't live knowing that we have a child out there,' so we knew we had to do something different."

Kimmi and Ryan Carlos found out about the Snowflakes Embryo Adoption Program early in their infertility journey when they were exploring all of their options by attending an adoption seminar at Nightlight Christian Adoptions.

Since the Snowflakes program was created in 1997, children born to families receiving embryos donated through the agency have been called "snowflake babies." The name of the program and the resulting term is derived from the fact that "like natural snowflakes, human embryos are frozen, unique and a gift from heaven," according to Kimberly Tyson, the Marketing and Program Director of the program.

The term "snowflake babies" caught on and people now often use the term for any baby born as a result of an embryo adoption or donation.

The last office census of embryos in frozen storage was conducted in 2011 and calculated over 612,000 embryos in frozen storage in the United States. Some estimates of embryos in frozen storage are now pushing 1,000,000.

Tyson estimates that about 70 percent of frozen embryos currently in existence are being held for use by the people who had them created, 14 percent will be abandoned, donated to science, 8 percent will be donated to science, and the remaining 8 percent will be adopted or donated for reproduction.

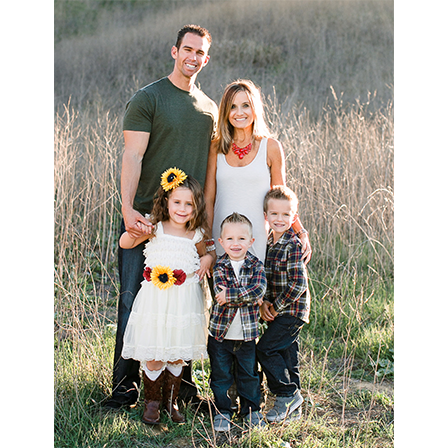

From L to R: Chloe, Easton and Clayton Carlos, ages 5, 3 and 5, respectively. (Photo provided by Carlos family)

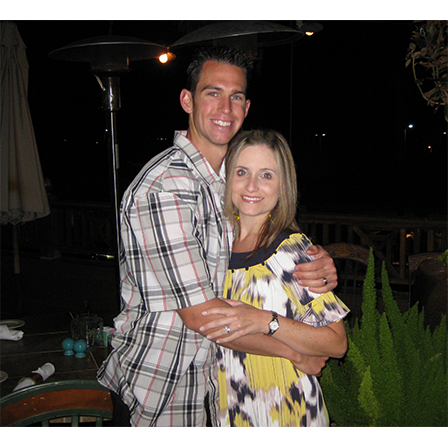

Ryan and Kimmi Carlos during their "trying time" in 2008. (Photo provided by Carlos family)

"Our two little perfectly healthy miracles on May 5, 2010."

— Kimmi Carlos (Photo provided by Carlos family)

Clayton Joseph Carlos on May 5, 2010. (Photo provided by Carlos family)

Chloe Grace Carlos on May 5, 2010. (Photo provided by Carlos family)

Easton James Carlos on April 3, 2012. (Photo provided by Carlos family)

Carlos family picture day in 2015. (Photo provided by Carlos family)