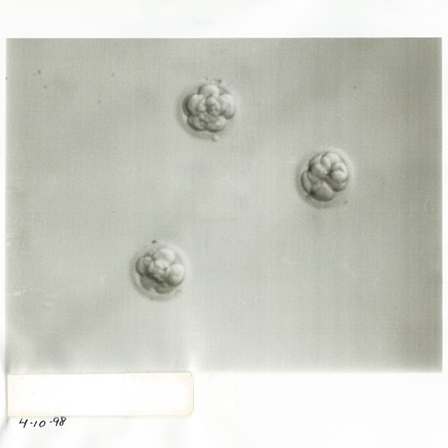

A photo of the embryos adopted by Marlene and John Strege on April 10, 1998,

the day they were thawed, one of which would eventually become Hannah Strege,

now 17 years old< and the first Snowflake Baby. (Photo provided by Strege)

Infertility treatment options have expanded rapidly since the landmark event of the first baby created by in-vitro fertilization (IVF) nearly 40 years ago. In the last two decades, science has evolved to where such embryos are not only being born, but they're being frozen for future use, possibly to end up donated or adopted.

The terminology is confusing, and if you spend any time talking to the parent of a child who came to life from donated or adopted embryos, you're bound to offend someone. When you get down to it, the real difference is whether the genetic material that makes up the child came from anonymous donors, or an open adoption where the new parents receive information about the biological parents.

Marlene and John Strege, San Diego parents of 17-year-old Hannah Strege, had a hand in the development of what is now known as the Snowflakes Embryo Adoption Program when they had trouble conceiving with their own eggs and sperm, and approached Ron Stoddart, former executive director of Nightlight Christian Adoptions in Anaheim, California, about adopting embryos.

"We wanted to do everything like a regular adoption," Marlene Strege says. The couple was willing to complete adoption education classes, undergo background checks and an in-home study and face the scrutiny of social workers before she and her husband could be approved to adopt embryos.

Stoddart signed on and went to work creating the Snowflakes Embryo Adoption Program as a companion to Nightlight's existing domestic and international adoption organization. To date, well over 1,000 babies have been born into families specifically using the Snowflakes Program's model, says Kimberly Tyson, Snowflakes' marketing and program director. Hannah Strege was the first one.

Formal embryo adoption isn't the only way to go, though.

You can now also have embryos donated to you, as was the case for Ariane Fleiderman, a Los Angeles accountant and mother who gave birth to twins at the age of 50 through another couple's anonymous generosity.

A very pregnant Ariane Fleiderman, then age 50, at work

in late summer 2013. (Photo provided by Fleiderman)

When Fleiderman and her husband, Mauricio Borges, an auto mechanic, were told by Dr. Sam Najmabadi, reproductive endocrinology infertility specialist at the Center for Reproductive Health & Gynecology in Beverly Hills, that it was unlikely she could get pregnant with her own eggs, she thought she was out of options because she could not afford to pay for an egg donor.

But the doctor had good news.

A couple had donated extra embryos to his clinic and he offered them to Fleiderman and Borges. They accepted the donation and their resulting children, a boy and a girl, will be 3 years old in September.

The main difference, besides the cost, between these two scenarios is the donors who donate directly at the fertility clinic most often choose to remain anonymous.

Tyson says the opposite is true of embryo adoptions through agencies like Snowflakes. "The essence of our embryo adoption model is to encourage open relationships between the donor and the adopter," she says. The communication methods and frequency are mutually agreed upon between the two parties.

In a formal embryo adoption carried out through an agency like Snowflakes, the process is akin to traditional adoption, including background checks and the biological family playing an active role in the choice of prospective parents for their embryos. All of these steps are completely voluntary, as there are no legal requirements for embryo adoption.

The cost for this service is about $8,000 and does not include the cost of background checks or medical fees associated with the actual embryo transfer.

Najmabadi says his clinic only charges for the medical services involved in the transfer process, making it a less costly alternative to becoming a parent than other options. Each transfer attempt costs around $3,000.

"[For patients trying to get pregnant who will] have to use an egg donor and a sperm donor, parenthood becomes expensive and out of reach for a lot of people," Najmabadi says. "Here, we take embryos that have already been donated to the clinic and we then donate them to [appropriate] patients for free."

Securing an egg donor and going through the IVF process, for example, can cost close to $30,000 — 10 times as much as the medicals costs associated with an embryo transfer.

"It was beyond a generous offer," Fleiderman says.

Once Fleiderman decided to go forward with the donation, she let Najmabadi choose the donor. "I didn't want to pick, because it didn't sit right at the time," she says. "It felt like shopping. Letting the doctor choose made it feel more natural."

Najmabadi says when it's left up to him, he tries to select embryos that come from biological parents with similar physical characteristics to those of the parents-to-be.

"We try to match the prospective parent with a close match in race, eye color and hair color of the donor," Najmabadi says. "For example, if someone comes in with blonde hair and green eyes, we would go through our data bank and say, 'OK, we have maybe one donor that matches them, or three donors that match them,' and then we present those options to the patient."

He says he can describe the donors' characteristics to the would-be parents but can't show any pictures due to doctor-patient confidentiality.

Is Anonymous Donation in the Best Interests of the Child?

Wendy Kramer, co-founder of the Donor Sibling Registry,

in her home office in Colorado. (Photo provided by Kramer)

Some question whether confidentiality is in the best interests of children.

Wendy Kramer, co-founder of the Donor Sibling Registry, a website that exists to "assist individuals conceived as a result of sperm, egg or embryo donation that are seeking to make mutually desired contact with others with whom they share genetic ties," is an outspoken opponent of anonymous donation.

"I thought for many years, if I came out against anonymous donation, because my son was created with anonymous donation, somehow that would negate my child," Kramer says. "It would negate his right to exist."

Her son, Ryan, was born 26 years ago with the help of an anonymous sperm donor. He co-founded the registry in 2000 with his mother and advocates ending anonymous donation.

Once Ryan told his mother that he didn't agree with anonymous donation, Wendy felt she had been given the greenlight to share her true feelings on the matter.

"Ryan was saying, 'Yes, I'm happy to be alive, but should there be anonymous donation? Of course not.'" Kramer says. "That gave me the freedom to say it also."

The Kramers oppose anonymous donation because it limits access to important information, like medical and family histories.

Their registry enables people on all sides of anonymous donation to post things, with varying degrees of identifying information. At the very least, it allows anonymous donors to update medical information tied to their donor identification numbers, to alert those who share their biological makeup of anything that might be important to know.

There's also the issue of random meetings between people who share the same biological donor genetic material.

"One family met their donor and realized he was part of their family," Kramer says. "Not by blood, but [they] had been going to weddings and family functions with this guy for their entire lives and they didn't know that this was their donor. He was just a part of their family by marriage."

"We have to think that older kids, young adults, adults are also having random meetings," Kramer says. "Have two of them met already and had a relationship? Who knows? It's not something they're going to go running to the press about."

That possibility is now amplified by our ability to freeze embryos created with anonymous donor material, giving rise to the potential for full biological siblings to be separated in age by years, even decades.

Ad for egg donation that appeared in Stephanie Haney's Facebook feed on March 20, 2016.

(Photo: Stephanie Haney/Annenberg Media)

Imagine a situation where you come across a person who came to life through an embryo from an anonymous donor. You feel a connection to them because that's how your parent was born, and you begin a romantic relationship. Then you find out, or worse, you don't, that the person is your biological aunt or uncle.

Welcome to the future.

You might think that's not likely because people who donate embryos aren't often donating a massive amount of them. But it's more complicated than that. Some donated embryos were created with the help of egg donors or sperm donors themselves. In those cases, what we're getting into is third-party anonymous donation.

"It's a lot of kids in college who are trying to pay tuition, right?" Marlene Strege says. "These clinics, they have these ads. Very altruistic, 'Oh, help a family fulfill their dream of having a child. Donate your sperm.'"

Strege says that worries her, and other mothers she's talked with, particularly given the frequency someone can donate sperm.

"I saw one documentary where a sperm donor had fathered over 300 children," Strege says. "And those are just the ones he knew about. That's crazy."

The Kramers are doing their part to put an end to anonymous donation by partnering with egg donation clinics. "We've got [about] 25 of them now who are writing the Donor Sibling Registry into their intended parent and donor contract," Kramer says. "So right from the beginning, these people are connecting with their donors anonymously on our website."

Kramer is not optimistic, however, about sperm banks agreeing to do the same. Until that happens, she contends the donor system is not serving the best interests of the children.

"If you really want to p**s off adopted people and donor conceived people, give the argument, 'Well you should be happy just to be alive,'" Kramer says. "What about children born from rape. Does that make rape okay? Yes, they're happy to be alive. Do the ends always justify the means? No. You can have a child that's happy to be alive. Does that make anonymous donation right? No. It's not a valid argument. Yes, people are happy to be alive but that doesn't make the methodology okay."

Strege differs from Kramer's point of view here. She acknowledges for the frozen embryos already in existence, it's not ideal to discard them if they can only be brought to life through anonymous donation.

"Those children still need homes, no matter how they were created," she says. "I'm just trying to say, moving forward, that I think it's in the best interest of the child to not be created using donor parts."

For Fleiderman, she sees herself as an adoptive mother, just like Strege. She even went to an adoption counselor to get advice on how to broach the subject of how her twins were brought into this world with her children.

The counselor suggested bringing up the topic early, before the twins might feel like something was being kept from them.

"I'll start with age-appropriate dialogue, as soon as they're old enough to understand babies, like puppies and kitties in their mommies' bellies," Fleiderman says. "I'll tell them, 'Mommy needed help to make babies and the doctor gave mommy help to make babies,' or something like that."

The Fleiderman-Borges twins playing on May 22, 2014. (Photo provided by Fleiderman)

When asked about how she will handle it if the twins want to some day meet their biological family, Fleiderman says she is open to it.

From the group of embryos created by the donating couple, her twins have at least one sibling that she knows about. "They were conceived at the same time, but if they were ever to meet their sibling, their sibling would be eight years older than them."

If the couple is open to it, Fleiderman and Borges have no problem with helping that meeting along. Dr. Najmabadi says it hasn't happened yet, but if a recipient of gifted embryos or the resulting children wanted to meet their biological donors, he would also be open to bringing up that issue for discussion with his patients.

Fleiderman says she does not feel threatened by the possibility of bringing biological family members into her family dynamic — and she hopes other women having difficulty conceiving might come to the same realization. "I would tell women not to sweat making it their egg, and men not to sweat making it their sperm," she says.

Borges says of embryo adoption that he's just happy that Fleiderman can experience motherhood.

Fleiderman is emphatic that the process she went through, which she also calls embryo adoption, is fantastic for couples who feel like they're out of options. "If there's one thing I could do for women and couples, I would scream about it from the rooftop," she says.

Fleiderman says that even though it's not her and her husband's DNA they're passing on, they connected with their children in a profound way by experiencing pregnancy and childbirth.

"I always tease people and say, 'I beat the fertility clock. I told you I would,'" she says. "And I was my own petri dish! How about that?"