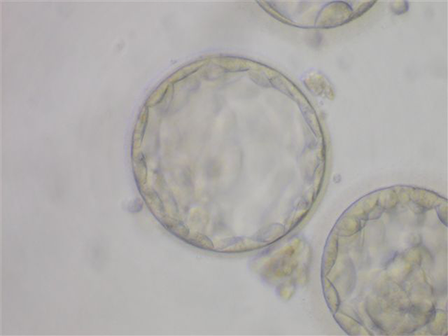

A photo of "Embryo B" which would eventually become one of Jalesia

McQueen's 8-year-old twin sons. (Photo provided by McQueen)

The world of fertility law is complex and unpredictable, while at the same time full of forms that have become de facto standard practice. The unpredictability is evident in a common clause found on many forms:

"We understand that the legal status of cryopreserved embryos, and related issues of use, ownership, custody, inheritance, child support, and rights upon death, divorce, abandonment, or other contingencies are uncertain and may change."

Those words "are uncertain and may change" don't strike much confidence in the hearts of people signing these forms. Neither does this sentence:

"We acknowledge however that the IVF program and/or [fertility clinic] cannot guarantee that the choices we have made here will be followed in every instance, since changes in laws, ethical standards, technologies, our circumstances, or program operation could change or limit the choices available over time and affect the Program's ability to follow our stated preferences."

The quotes come straight from a medical consent form signed on Sept. 29, 2010, by Dr. Mimi Lee and Stephen Findley, a San Francisco couple who chose in vitro fertilization (IVF) to preserve Lee's fertility, because she had just been diagnosed with cancer, 10 days before their wedding.

According to Lee, this form was one of many that had to be signed before she could begin the IVF process, which had to be done immediately. Once she started cancer treatment, she was told by her doctors she could not attempt IVF again.

So Lee, an anesthesiologist and concert pianist, and Findley, an investment executive, signed the forms, agreeing to discard any frozen embryos that may not have been used in five out of six scenarios, with the one exception: the death of Findley, in which case Lee would own all rights to any remaining embryos.

The two never imagined they'd separate three years later, and become embroiled in a legal battle over this exact form that would stretch on for more than two years.

A version of the same thing happened to Jalesia McQueen, lawyer and mother living in St. Louis, Missouri, when she and her ex-husband, Justin Gadberry, divorced nine years after freezing embryos created with her eggs and his sperm.

At that time, McQueen did exactly what Lee and Findley were required to do when creating and freezing embryos to preserve their options for having children at a later date. McQueen and Gadberry expressly documented what their fertility clinic should do with their embryos if one or both of them died, or they divorced.

They also did this on a medical consent form, filed with their clinic.

"[We had a] 2010 agreement that actually has the writing in there that says in the case of divorce or separation, I will get them," McQueen says. That agreement existed because McQueen and Gadberry switched the storage location for their embryos, so they had to fill out all new forms.

"In 2007, he had signed the same agreement with the same provisions in them [for the original storage location]," McQueen says. "He had signed it twice."

According to court documents, Gadberry admitted in court that he signed and initialed a consent form granting McQueen use of their embryos in the event of divorce, but said he didn't know what he was signing.

Gadberry contends that even though he did sign the agreement, he "doesn't know when 'to be used by Jalesia McQueen' was written in" on the page of the consent form that discusses what should be done with any remaining frozen embryos in the event of Gadberry and McQueen's divorce, according to Tim Schlesinger, attorney for Gadberry.

The trial court sided with Gadberry, declared the consent form unenforceable as a contract for a variety of reasons, including the following: the form was notarized on May 15, 2010 but portions of the form were not signed until May 21, 2010, there was no consideration for the agreement, there was no provision stating what Gadberry's rights and obligations would be in the event that McQueen had children from the embryos, there was no indication that Gadberry understood that his interests in this matter would be adverse to McQueen's, Gadberry was not represented by an attorney nor was there indication that he knew he could or should be, plus one more reason.

The court said the indication on the form that the embryos should go to McQueen was an advance directive that could be changed at any time, which the court said Gadberry was free to, and did, rescind orally and in writing after dissolution paperwork was filed.

The court then ordered the two embryos in question remain joint property in cryo-preservation until the two can agree on what to do with them.

It must be nice to get out of agreements like that," McQueen said. McQueen is appealing that decision. She also created a group called Embryo Defense, not only to provide resources to other people in similar situations, but also to reform the law and push legislation in her home state of Missouri.

Fertility law expert Richard Vaughn discusses the current state of fertility law in the U.S.

(Click here if this video doesn't play.)

The average person might think if these forms are so complicated they are open to misinterpretation, lawyers would be involved to help explain and properly execute these agreements.

But lawyers in the field of assisted reproductive family law don't get many requests to review medical consent forms. When they do, for the most part, those requests are referred to legal professionals who focus on the responsibilities of the fertility clinic to its patients, and vice versa, according to Richard Vaughn, chair of the American Bar Association Family Law Section on Assisted Reproductive Technology and managing partner of the International Fertility Law Group located in Brentwood, California.

The main purpose of a medical consent form is to make sure the patient is acting with informed consent, meaning the patient knows exactly what the doctor will do, which protects the doctor from the patient later saying he or she acted without the patient's permission.

In the case of IVF treatments that may result in frozen embryos, clients often see an extra instructions.

"The one thing about those consent forms that crosses over to the law is that they often have disposition statements in them about what to do with any remaining frozen embryos," Vaughn says.

What's troublesome about that cross-over is that medical consent forms, also referred to as advance directives, can be updated or changed at any time. This is true even if the form doesn't expressly state that your decisions as recorded on that document can later be changed.

But these forms often do expressly state just that.

The consent form in the case of Lee and Findley reads, in part, "We understand we can jointly change any of the choices made herein by contacting the IVF Program Director and signing a new agreement incorporating any new choices and decisions which are available to us and on which we both agree."

But that provision wasn't particularly helpful to Lee, who was not permitted to change her mind about what she agreed to on a medical consent form.

The Medical Consent Form as an Enforceable Contract Between Partners

Dr. Mimi Lee playing piano at the San Francisco Community Music Center.

(Photo provided by Lee)

Just as it happened for McQueen, Lee lost her battle at the trial court level to gain ownership over her frozen embryos, but by the opposite reasoning. A San Francisco trial court chose to uphold Lee's consent form as a binding contract between her and her ex-husband, in a decision handed down in Nov. 2015.

Had Lee been counseled to freeze some of the eggs retrieved during her IVF cycle, she acknowledges she might not have ended up in court fighting for her embryos.

"I was given the statistic when we went in, and it was just one visit that we got all this information, that given my age, the likelihood of me having a live birth with any of my eggs anyway was maybe 20 percent," Lee says. "I was not expected to have a lot of eggs."

But Lee successfully produced 18 eggs, with 12 selected as good candidates for fertilization.

"Given that we were newlyweds, the fact that we were in a stable relationship, my age which was 41 at the time, the age of my eggs, we were counseled [by the fertility clinic] to freeze all as embryos and not to freeze any as eggs," Lee says. "Ultimately, we made the decision we did because I was told the current state of technology was just not as good for frozen eggs-to-baby as it was for frozen embryos-to-baby."

So Lee and Findley fertilized all 12 eggs, which produced five embryos the clinic deemed most likely to result in a live, healthy baby.

"Since my cancer was estrogen receptor positive, doing IVF [in vitro fertilization] itself was a risk because part of the injections that you give yourself in order to stimulate the ovaries is estrogen, so we made this decision very quickly," Lee says. "We started the cycle immediately while we were still gathering information on how I was going to treat my cancer, because I was also told that after I started my cancer treatments, no more IVF attempts could be made."

It was during this whirlwind that the consent form was signed that directed the fertility clinic on what to do with any embryos if Lee and Findley were to divorce.

When the two separated in 2013, Findley told Lee he did not want to have children with her, so he would be holding her to the form's declaration that upon divorce, the embryos be discarded.

"At the time, we were signing consent forms left and right for all sorts of tests and things relating to the cancer," Lee says. "This was just another consent form we signed."

According to Lee, she admitted in court that she signed and initialed a consent form granting the clinic permission to discard their embryos in the event of divorce, but said she didn't know what she was signing.

Does it feel like you read that paragraph before? You basically did, only with the names McQueen and Gadberry in it.

And this time, the paragraph that follows describes the flip-side of the scenario.

The trial court sided with Findley, enforcing the consent form as a binding contract between Lee and Finldey, rather than finding the form was only a binding contract between their fertility clinic as one party, and Lee and Findley together as a second collective party, and ordered that the embryos in question be discarded.

"In the end, it was the thing that prevented me from having my children," Lee says. "All of the counsel that I had spoken to and the support that I had knew it was going to be a fight, but also said it was going to be potentially a great opportunity for the court to open the doors to really create some sort of legal precedent to address some of the issues around embryo disposition."

Lee chose not to appeal the San Francisco trial court's decision because she was emotionally and financially exhausted from the ordeal. That means for her, her last opportunity to have biological children was gone.

Developing Trends in Embryo Disposition Cases

Jalesia McQueen with her sons in 2014. (Photo provided by McQueen)

For McQueen, who has three children total (two with Gadberry, one from a later relationship), it was never about preserving her fertility. It was initially about having children with her then-husband when the two were physically separated due to his military service.

McQueen's two oldest children, 8-year-old twin boys, were born from the same set of embryos that are now frozen. So now it's about fighting for the would-be siblings of her children.

We had four embryos and two of them were implanted," McQueen says. The other two were frozen and are the subject of McQueen's battle with Gadberry. "This is very real to me. This isn't theoretical. This isn't, 'What if?' or 'What would they look like?' I look at my kids every day and I think to myself, 'This could have been them.'"

Although Lee and McQueen seem to be at odds on this issue, with one arguing against enforcement as a contract and one arguing for it, they're actually not.

McQueen is now using her legal background to make a case against what she terms government-forced termination over the objections of parents, in all scenarios.

McQueen's research shows that as things now stand, when enforcing consent forms as contracts would result in discarding embryos, they are being enforced, and when it would result in allowing the embryos to be brought to life, they are being declared unenforceable, in states across the U.S.

She's not wrong.

The outlier here is the Chicago 2014 case of Karla Dunston versus Jacob Szafranski, where Szafranksi, a long-time work-place acquaintance but newer romantic partner, agreed to provide his sperm to recently diagnosed breast cancer patient Dunston to be combined with her eggs and frozen as embryos.

The process was carried out 13 days later. Five months after that, Szafranski sent Dunston an email that said he changed his mind.

Szafranski then sued Dunston to prevent her from trying to bring the embryos to life.

That case was decided in favor of Dunston. The trial court ordered that the phone call was an enforceable oral contract and declared that the embryos in question be surrendered to the full custody of Dunston. Szafranksi appealed in 2015, and lost.

The distinction here seems to be that both Dunston and Szafranksi openly acknowledged they never planned to marry or parent any resulting children together. The question has become one of status: intended parent or donor.

The Fight Over Frozen Embryos Moves to the Missouri Legislature

This inconsistency in the law is what prompted McQueen to start an organization called Embryo Defense. The organization's website says it aims to be a resource for all parents, advocates, lawyers and anybody else interested in saving frozen embryos.

One channel McQueen is using to advance her goal is working to pass legislation in Missouri that would prevent the state from ordering destruction of embryos against one parent's wishes, in any situation.

"Our group transcends all political and religious lines when it comes to saving lives," says the site. But McQueen and her organization are very clear that they consider embryos to be life at that stage of development.

A photo of "Embryo A" which would eventually become one of Jalesia

McQueen's 8-year-old twin sons. (Photo provided by McQueen)

"Life begins at conception. That is science. Nobody in their right mind can argue that," McQueen says. "Because if my embryos were on Mars, we would be jumping up and down saying, 'We saw life on mars.'"

When asked if she thinks protecting embryos outside the body would affect other women's issues, like the right to terminate a pregnancy, McQueen is quick to clarify that the issue here is not pro-life versus pro-choice.

McQueen says the differentiating factor is the intent with which an embryo is created. You cannot go through IVF without the intent of creating an embryo, whereas people have sexual intercourse every day for non-reproductive purposes, where an embryo results that did not arise from that very specific intent.

"I don't think we have to go back to science class and figure out when life starts. When a sperm hits an egg and gets in there, that's you," McQueen says. "Because you can't skip that step and get to a full-blown adult. When along the way do we assign rights to that embryo or to that life? I think that's the real question."

But even so, that's not the question McQueen is trying to answer with her work to protect her embryos and the embryos of other parents embroiled in similar battles.

She says the issue is pro-parent.

"Our purpose is to educate the public on respect for the life of a human embryo," the site says. "We believe in taking responsibility as a parent and educating pro-life advocates, leaders and clergy on how to articulate a proper defense for human embryos created."

Outspoken anti-abortion groups providing support in these cases, including in McQueen's appeal, may confound the issue, though.

Missouri Right to Life, Lawyers for Life and the American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians & Gynecologists have filed together a brief of amici curiae in her case, meaning they seek to argue the interests they see fit on her behalf, as "friends of the court."

The Thomas More Society (based out of Chicago) which filed a personhood claim in the on-going Santa Monica, California embryo disposition dispute between Sofia Vergara of "Modern Family" fame and ex-fiancé Nick Loeb, is also providing legal assistance to McQueen on her appeal.

Schlesinger says that McQueen is "unequivocally taking the position that frozen embryos are children, and that's something no court has ever done."

"It's important for all who seek fertility treatment and for all people who don't want to be made parents against their will, that Gadberry prevail," says Schlesigner, speaking on his client's behalf.

With such a split in outcomes on embryo disposition cases happening across the country, the issue of how to handle disputes these disputes is ripe for appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, which has heavy implications, particularly due to the vacancy in the court left by the death of Justice Antonin Scalia.

"This is definitely the political agenda finding its way into a personal dispute," Vaughn says. "There are political organizations out there, right-to-life organizations, that have tried to use these fertility litigation cases as a back door to the right-to-life agenda."

Extended cut interview: Fertility law expert Richard Vaughn discusses the personhood issue.

(Click here if this video doesn't load.)

While Vaughn didn't want to speculate on what effect any particular U.S. Supreme Court nominee might have on the issue of personhood, he did have thoughts on how the definition of life at the embryo stage would effect how fertility clinics operate.

"When you consider that an embryo is a person at the very, very, very early stage and there are frozen embryos and then they are discarded, then you've got clinics committing murder," Vaughn says. "It's a real issue that would completely put up barriers to people's right to procreate."

McQueen contends her goal is not to end the ability to terminate unwanted pregnancies through back-door means such as frozen embryo rights cases and legislation.

"The majority of women who I've spoken to that are in this situation are pro-choice women," McQueen says. McQueen is simply garnering support where she can, wherever she finds it.

"This is ill-considered legislation, that is unconstitutional if applied as proposed and would force people to become parents against their will," Schlesinger says about McQueen's bill.

Here's something to consider, in parting. States force teenagers to become "parents" all the time when a young man and woman get pregnant the old-fashioned way.

No one would ever dream of forcing a young woman to abort an embryo that was created en vivo, because the other party involved in creating that embryo didn't want to raise the child. In fact, there are many places where the aforementioned anti-abortion groups make a vigilant effort to bring about the exact opposite effect: to force pregnancies to continue, wanted or not.

What happens in those cases, sometimes, is that the "parent" who provided the sperm is forced to pay child support, or may end up with custody of the child, until the resulting child reaches adulthood. That responsibility seems to be what people are afraid of here.

But people with those fears may be forgetting about the other scenario. The one where the family that wants the child agrees to assume full responsibility for the resulting baby and absolves the sperm or egg provider of "parent" status, effectively turning him or her into a "donor."

McQueen says that the bottom line in her scenario is that she made a choice to make embryos to implant to have babies. It was no accident. And she would be happy to bring her embryos to life without any future involvement from or responsibility on Gadberry.

"It doesn't get any more intentional than IVF," she says. "We talk about Planned Parenthood. You can't get more planning for your parenthood than that."

McQueen's appeal was filed in December and her bill has had its first public hearings in both houses of the Missouri legislature. Next steps for the bill include review in select committees before it will have a chance to go to the floor of the House and Senate for a vote.

You can read the text of her bill here.