(Click here if this video doesn't play.)

Ariane Fleiderman-Borges and Mauricio Borges tried for six years — almost from the time they met — to become parents together. They conceived, naturally, just before Fleiderman turned 44 — and she miscarried a short time later.

"I made it less than a month," Fleiderman says. Her doctor at the time had warned her.

"He said right then and there, 'Your pregnancy's not going to last. You're probably going to lose it.' Because of my age," Fleiderman says. "And sure enough, I did. That was sort of the beginning of a long road."

The next year, in 2008, Fleiderman and Borges turned to artificial insemination. Again, Fleiderman achieved pregnancy, but around week five her OB-GYN told her she feared that Fleiderman had an ectopic pregnancy, which is when a fertilized egg implants outside the uterus, generally in a Fallopian tube. A few days later, she was given medication to stop the growth of the abnormally progressing pregnancy.

"My doctor gave me an injection in my rear that killed the embryo because they thought it was tubal," Fleiderman says. "I showed pregnant, but something was not normal about it."

Fleiderman recalls having a very hard time. "The emotional and financial strain of trying to get pregnant and having failed pregnancies, one after another, it's horrible."

But she and Borges remained undeterred.

Fleiderman's OB-GYN referred the couple to Dr. Sam Najmabadi, a reproductive endocrinology infertility specialist at the Center for Reproductive Health & Gynecology in Beverly Hills.

Najmabadi began his fertility treatment of Fleiderman and Borges with two more rounds of artificial insemination in November 2010 and December 2010, neither of which resulted in pregnancy.

"We tried again and again and again," Borges says. "I told her, 'Let's go, we can try again.' We only had a short time [to get pregnant] because of her age, so we tried and tried and tried."

Fleiderman says one of the reasons she was initially attracted to Borges was his willingness to have children with her. She definitely wanted to be a mother, and thought she had found a partner who could help her make that happen.

"I wanted her to be able to experience being a mother, because I already had children of my own and I wanted her to have that same feeling," Borges says.

Fleiderman tried one more round of artificial insemination in March 2011, which failed.

"He told me that was an indication that even if I went for full-on in-vitro [fertilization], my eggs were just not responding that well."

Then, in late spring 2011, Najmabadi, brought up another way she might conceive — with the help of an Arizona couple they'd never met.

Najmabadi says when a patient goes through the fertility treatment process and needs to use a donor egg, he considers embryo adoption.

Sitting in Najmabadi's office that spring day in 2011, Fleidermans long, complicated journey to motherhood came into focus.

"I was sitting there crying as he was talking to his nurse and then felt a divine assistance of some sort. I'm not a heavy religious person, but all of a sudden I felt compelled to ask, 'Is there anything else? Like embryo... or something?'" Fleiderman recalls saying, not really sure how to finish her own sentence.

"And then he looked up at me, and he said, 'You know, as a matter of fact there is. Every now and again people leave embryos behind with me.'"

Kai and Audrey's Journey to Life

A very pregnant Ariane Fleiderman, then age 50, at work

in late summer 2013. (Photo provided by Fleiderman)

A very pregnant Ariane Fleiderman, then age 50, at work

in late summer 2013. (Photo provided by Fleiderman)

The matured embryos that would become Kai and Audrey Fleiderman-Borges came from a group of six created and frozen seven years before Fleiderman asked the right question at the right time in her doctor's office.

An Arizona couple had been having trouble getting pregnant themselves, so they paid a donor to provide them with an egg to be fertilized by the husband's sperm. The couple went through the IVF process with Najmabadi and successfully had a baby.

Najmabadi says he works with patients from all over the world, including England, Australia, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia and China. He has patients from New York to San Diego and many places in between, so it's not unusual that an Arizona couple would travel to Los Angeles for his services.

Five years later, the couple decided that their family was complete and gave the doctor their blessing to donate their remaining half dozen embryos to other hopeful parents-to-be.

Fleiderman remembers Najmabadi pulling out a sheet of paper from under his desk calendar. The list contained the names of previous patients who had donated their extra frozen embryos to the doctor for gifting to couples in need.

And it was a short list. Of the roughly 40 percent of Najmabadi's patients who end up with extra embryos in cryopreservation, he estimates only 5 percent choose to donate their embryos to others.

Najmabadi says that he makes sure to include in his discussion with patients who have remaining embryos that donation is an option while they are at the office. He says otherwise, the first time they may hear about it is when it shows up as an option on their annual embryo storage bill, and that should be avoided.

"Most often the bills for embryo storage go out in January, so I'm on the phone a lot January, February and March with all the patients who I have gotten pregnant in the past who call to come in and discuss their options," Najmabadi says. "They ask, 'Can we make a decision together? Can you give us more information about it?' They're also concerned about what part, if any of their information will get out. They want to know, 'Are you going to show my information to this other person so they will know who I am?' So we reassure them that is not the case, and go through that process of education, and I think as we are educating them more, patients then are more willing to donate. But I never really push it, I just give it to them as an option."

Najmabadi told Fleiderman that he could gift her some embryos and that she would only have to pay for the implantation. The cost would come to about $3,000. Fleiderman says that once she took her ego out of it, she loved the idea.

"I thought, 'If I'm a true mother I want [my] children to have the strongest bodies possible," Fleiderman says. "So I should not try and insist they be from my eggs." The egg donor the Arizona couple used was 22 years old at the time the embryos were created. (Younger eggs are less prone to chromosomal abnormalities and other complications.)

Borges says he was willing to try everything to have children together, no matter what that was.

"The doctor told us it was impossible for us to have kids with her eggs even though she was very healthy and could carry the pregnancy, so there wasn't much else we could do," Borges says. "She asked me what I thought, and I said if you feel happy, if it's good for you, it's good for me, too."

There also was the cost factor. Securing an egg donor and going through the IVF process would come to about $30,000 — 10 times as much as embryo adoption. "It was beyond a generous offer," Fleiderman says.

Najmabadi says when matching his patients with donated embryos, he takes physical characteristics, the number of donated embryos available and the age of the donor at the time the egg was made into account (because the success rate of achieving pregnancy is mainly based on the age of the person at the time of producing the donated egg) and discusses those options with the patient, as well, before deciding on a donor.

Kai and Audrey's genetic parents most closely matched the look of Fleiderman and her husband, and made the most sense to Dr. Najmabadi in terms of the other factors, so their embryos were the ones chosen to come to life.

Embryo Adoption Doesn't Guarantee the Perfect Outcome

The process wasn't an immediate success. In June 2011, Najmabadi initially tried to transfer only one embryo, because Fleiderman didn't want to chance a multiple birth.

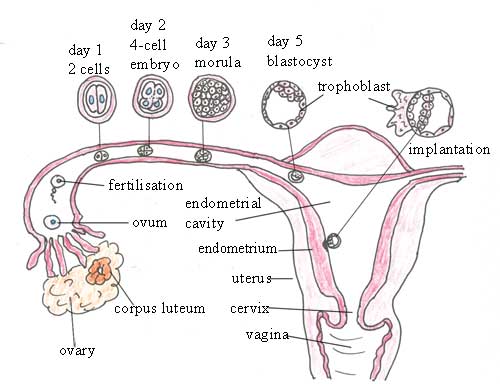

The embryo transfer process takes less than 10 minutes from start to finish. To prepare for this stage in the process, patients go through a series of oral estrogen supplements as well progesterone supplements taken by vaginal insertion.

The estrogen and progesterone supplements mimic what the uterus would be exposed to if it were experiencing a natural pregnancy. Within the first three to four days of their period, Najmabadi's embryo adoption patients start taking oral estrogen pills twice a day for about nine days. Then the dosage is upped to three times a day for about five days.

The last day of the oral estrogen supplement corresponds to the date in the woman's cycle when the eggs were retrieved that resulted in the donated embryos.

This synchronization process is important to creating a receptive uterine environment. By supplementing the natural cycle of the patient and trying to synchronize the uterus to the corresponding embryos, higher implantation rates are achieved.

Najmabadi usually starts the vaginal progesterone capsules the day after the eggs are retrieved in an IVF cycle, so that is the next step for his embryo adoption patients as well. These capsules are inserted three times a day for up to five days.

The embryos are thawed and inserted into the patient's uterus on either day three or five of the progesterone capsules, corresponding to whether the embryos were frozen on day three or day five after fertilization and growth. This ensures that the uterine environment syncs up with the developmental stage of the embryo, and then the embryos are thawed and put into the uterus.

On the scheduled day of transfer, he calls the patients in, they take a Valium and go to a dark room near the back of the clinic to relax. They sign their paperwork, some patients opt to receive acupuncture, and once the medication has kicked in, he begins.

"I go in under ultrasound guidance, put a catheter into the uterus and release the embryos into the uterus," Najmabadi says. "That's it. That's the embryo transfer process."

A sequential display of the human female reproductive system from

fertilization to implantation. (Photo Courtesy: OpenLearn Works)

The next step, the implantation process, is a little more complicated.

"Implantation is the process of an embryo basically digging itself into the uterus and taking. That process is an inflammatory process that takes a few days. Within the first one to three days [after the transfer], implantation will occur," Najmabadi says.

"The way it works is the embryo is dropped into the uterus as if it had come from the fallopian tube, but we're just putting it [in] from below instead of above," he says. "Then the embryo starts signaling the endometrium, and then there's cell-to-cell contact, and then invasion of cells into the endometrium and then growth for that baby.

"The process of implantation, once it's figured out, someone will win the Nobel prize, because there's a lot that we don't know about it," he says. "It is one of those places in my world that is the least studied and least understood."

The embryo successfully implanted into Fleiderman's uterine lining — but this pregnancy would result in another miscarriage. As Fleiderman put it, "It was a bad embryo; it had no yolk [sac]."

A certain percentage of frozen embryos are actually abnormal, and many times look no different than the normal ones. So embryo transfers are done regularly with the knowledge that some are abnormal.

"Many times abnormal embryos do not implant, or do not continue past a certain stage of pregnancy after they have implanted," Najmabadi says. "It is sometimes possible to get pregnant with an abnormal embryo that then results in a miscarriage."

Genetic screening and diagnosis is used more and more to test the genetics of each embryo. By doing so the odds of an abnormal embryo being transferred is much lower. However, Najmabadi says testing is invasive and expensive, so most embryo transfers are done without it.

Fleiderman had to have a procedure to evacuate this failed pregnancy on Aug. 5, 2011, on her 48th birthday. "That one was probably the hardest," she says. "That was really hard."

Fleiderman and Najmabadi tried again in Dec. 2011, this time with two embryos. But neither would implant into her uterine wall. Fleiderman feared the stress of the loss of her mother, who had died from Lymphoma, was not helping the situation, so she decided to take a break.

"Then my husband got himself detained," Fleiderman says.

"I made the mistake of getting arrested while driving without a license and that put me in a very bad situation," Borges says. "They arrested me first in San Francisco. And then they sent me to immigration. They were going to deport me back to Brazil."

Borges was first sent to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement's Contra Costa West County Detention Facility in Richmond, Calif. before being relocated to the Adelanto Detention Facility in Southern California.

Immigration laws got more complicated after the Sept. 11 attacks; merely being married to a U.S. citizen is no longer a path to getting a green card if a person didn't enter the country legally in the first place. Because Borges entered the United States illegally in 2002, his marriage to Fleiderman, a U.S. citizen, is irrelevant to his immigration status.

With her husband stuck in Adelanto, Fleiderman decided to push ahead and try to get pregnant again.

Becoming a mother was important to Fleiderman, and with limited contact she did not feel like she needed to consult with Borges about moving forward. The decision had already been made.

This time, Najmabadi suggested trying to implant all three of the remaining embryos. But Fleiderman told him she wasn't sure she could handle it if all three happened to take, so she wanted to try with two embryos instead.

The doctor agreed and they scheduled the transfer procedure.

Fleiderman says that on that day in February 2013, she showed up for the procedure at her most relaxed yet. "I went in by myself, popped the Valium I was prescribed, relaxed and fell asleep after the transfer," she says. "It felt a lot like a pap smear and only takes about an eighth of a second. And bam! I was pregnant."

More Hard Choices

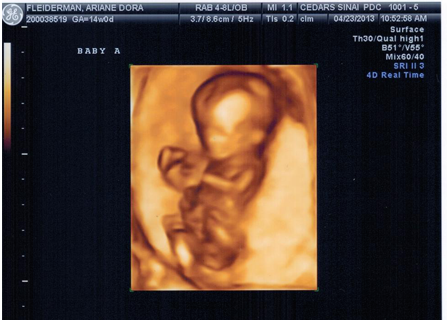

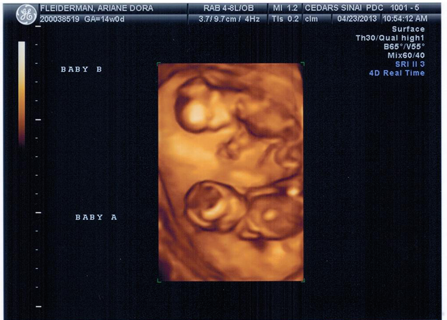

An image of Kai ("Baby A") inside Fleiderman's womb

from April 23, 2013. (Photo provided by Fleiderman)

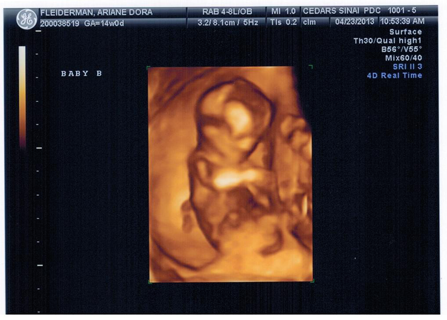

An image of Audrey ("Baby B") inside Fleiderman's womb

from April 23, 2013. (Photo provided by Fleiderman)

It took weeks before Fleiderman's blood test showed that both embryos had successfully implanted.

Fleiderman admits that when Najmabadi confirmed she was pregnant with twins, she felt torn.

"At that point I was so tired, they could have told me I was going to give birth to Martians and I would have been like, 'OK, that's fine. What time do I need to report for the birth?'"

But at other times, she says, "I definitely freaked out that there were two." She was still unsure of her husband's residency status.

Borges' immigration lawyers were telling Fleiderman there was a 50-50 chance of Borges being deported to Brazil. "I was anticipating that I would basically be a single mother," she says. "A single mother of one was daunting enough."

Fleiderman says she'd started thinking about articles she'd read that describe complications with multiple births — and situations where embryos were removed to save other embryos, or because the number of births posed a risk to the mother's health, or even because the parent wasn't able to properly care for that many children. She also says that one of the embryos was having trouble attaching to her uterus.

So she asked about embryo reduction.

Embryo reduction is performed by only a few doctors in the Los Angeles area, and Najmabadi isn't one of them. It's a process where the doctor removes one or more embryos after an IVF cycle to give the other embryos a better chance of survival.

An image of Kai ("Baby A") and Audrey ("Baby B") inside Fleiderman's womb

from April 23, 2013. (Photo provided by Fleiderman)

Then the doctor showed her an ultrasound image of the two embryos and let her listen to their heartbeats.

Fleiderman says she thought to herself, "Well, I'm kind of old to be having these babies, so I'll keep them both — so when I'm senile, they'll have each other."

But she wasn't quite done with exploring her options just yet.

Even after Fleiderman decided to move forward with both embryos, she wasn't sure she could handle raising the two of them — especially if her husband were to fail to get U.S. citizenship. She asked her cousin, who is gay, if he would be willing to raise one of them as a co-parent, and she scheduled an appointment to meet with an adoption counselor.

After missing her appointment three times, Fleiderman says she was hit with another realization. "One day I just looked down at my belly and I said, 'OK I get the message. You guys don't want to be separated.'"

Embryo Adoption is Still Adoption

Fleiderman did eventually meet with the adoption counselor. "I still wanted to hear what this lady had to say," she says, "because one day I'm going to have to explain to my kids what I did, which is embryo adoption, so the word 'adoption' is still in the formula."

The counselor suggested bringing up the topic early, before the twins might feel like something was being kept from them. "I'll start with age-appropriate dialogue, as soon as they're old enough to understand babies, like puppies and kitties in their mommies' bellies," she says. "I'll tell them, 'Mommy needed help to make babies and the doctor gave mommy help to make babies,' or something like that."

Fleiderman also took a lot of photos during the pregnancy, so the twins will know she carried them.

About halfway through Fleiderman's pregnancy, Borges was released from detention pending a deportation hearing. The immigration lawyers seemed to think the result would be one of two extremes: he would be granted a green card or sent on his way to Brazil, his place of birth.

"I really worried about her, because she was so big and pregnant," Borges says about Fleiderman's condition while he was detained. "It wasn't easy for her, being 50 and pregnant with twins. And she helped me with lawyers, all the papers, everything to get me out of there."

Borges says when they let him leave Adelanto in May 2013 pending his hearing that it was like "a gift from God."

With Borges released for the time being, Fleiderman was free to focus on maintaining her health and trying to enjoy the experience of pregnancy as much as possible.

Pregnancy was not comfortable with twins, at 50, at all" Fleiderman says, with a laugh. "My feet expanded a size and a half!"

Audrey and Kai playing on May 22, 2014. (Photo provided by Fleiderman)