Surgery

F

inding a surgeon can be an equally stressful process to procuring funding.

Just as Hopwood and Olson-Kennedy will avoid putting pronouns in letters to insurance companies, they also avoid including pronouns in letters to surgeons. In Hopwood's experience, some of the best surgeons performing top surgery won't perform the procedure on nonbinary patients, let alone cis women.

"It's like groundhog day—the same argument, the same resistance, the same problems," Hopwood said describing surgeons he comes in contact with during his national and international gender-affirming care trainings. "For these providers, it all comes back to the argument that top surgery is harmful and they signed an oath to do no harm."

In order to prep his nonbinary patients to see these resistant surgeons, Hopwood has a candid discussion with the patient about whether or not this is tolerable for them, and if so what they need to cope with being misgendered for a temporary period of time. "Sometimes dealing with these surgeons is the only way patients will get the care they need," Hopwood said.

Yale Assistant Professor Greta LaFleur, who got top surgery a few years ago, argues the "do no harm" line of reasoning for refusing care to nonbinary patients is baseless.

"I can heal up, and the second I heal up I could lay down $6,000, get a boob job, and I don't have to go through any of this trash," LaFleur said. "So the do no harm idea is ridiculous, because harm apparently only goes in one direction."

Harm apparently only goes in one direction

Dr. Kryger, who has seen an increasing number of nonbinary and cis female patients over the past few years, has noticed this uni-directional understanding of harm among his colleagues. "Bias is social," he said.

"It was never a problem when women wanted to put silicon balls in their breasts—no one in society was quick to judge them," Kryger said. "They're totally fine with putting bags of salt water that could burst in there, but if a woman wants to remove her breasts suddenly it's like, 'oh, there must be something wrong!' So there's a huge bias there."

LaFleur experienced this bias first-hand during routine pre-surgery care when a doctor held their blood work hostage until LaFleur agreed to come back into the office to discuss this "really big decision." LaFleur, who already had to go to six months of therapy to be qualified for the surgery, asked the doctor "what makes you think, as someone who's met me for 15 minutes, that you are qualified to make this decision or make an evaluation and be the gatekeeper?" When she responded, "well, I'm a doctor," LaFleur responded back with "well, so am I."

There is a pervasive lack of awareness among medical professionals regarding the expansiveness of gender identity, making even routine visits like blood work turn into a pathologizing and stigmatizing of the patient.

"I don't understand why we have this weird sanctity around the naturalness—the quote-on-quote 'naturalness'—of the body," LaFleur said. "It's ridiculous—we're changing our bodies all the time."

Kryger agrees. "I'm not going to tell a woman, 'you need your breasts,' because you don't need your breasts," he said. When explaining the concept of top surgery to those unfamiliar with the procedure, and especially to those who react negatively to the idea of someone who's not FTM removing their breasts, Kryger points to the breast's only two functions. "The breast has a biological function, which is nursing, and a psychosocial function as a sexual object—used as a part of a woman's femininity and sexuality," Kryger said. He then points to the breast's major disadvantage as the number one source of cancer. "So, if a woman is never planning on nursing and doesn't see her breasts as a positive sexual object, then that leaves cancer and the breasts have no positive function at all."

Breast removal, however, is far from a one size fits all. The first step in providing a gender-affirming environment in which the patient can feel comfortable freely discussing their surgery outcome desires is to have a discussion about gender. Describing Dr. Mosser’s approach, Rose said he "begins each consultation repeating his pronouns, he/him, and asking the patient what pronouns they use because gender is fluid and pronouns can change."

I'm not going to tell a woman 'you need your breasts' because you don't need your breasts

Listening openly to what a patient wants their body to look like and how they want to feel in it is key to empowering patients to choose the right top surgery method for them, Rose explained.

And for a group of people whose experience with the health care system has been marked by stigma and discrimination, establishing this foundation of trust can relieve anxiety surrounding what can be an incredibly stressful process.

"I'm going to tell you a story that'll make you cry," Boyask said. He described waiting in the doctor's office before his first consultation, getting ready to disrobe when Dr. Beverly Fischer walked in. "She right away made a comment I will never forgot in my whole life," Boyask said. Fischer told him: "I totally understand if you're nervous, so take as much time as you need. I really get that for most of the people that I'm working with this part is actually a lot scarier than the actual surgery."

It's scary "because they had to take pre-op photos and you're very exposed," Boyask explained. "And that spoke volumes to me that she understood that."

Arnon, who chose to get top surgery in the U.S. rather than in Israel, had a similarly affirming experience with their surgeon, Dr. Daniel Medalie. "He was very politically correct and aware of the terms and what's appropriate to ask or say to someone," Arnon said.

If Arnon got the procedure done in Israel, they would have had only two surgeons to choose from. "Neither is very good, and I would have had to pay more than I did in the U.S.," they said. "Dr. Medalie and his staff were so nice—they even got mad at my wife because they thought she was misgendering me, but I just go by different pronouns in hebrew."

"The whole experience was amazing."

CLICK TO ENLARGE

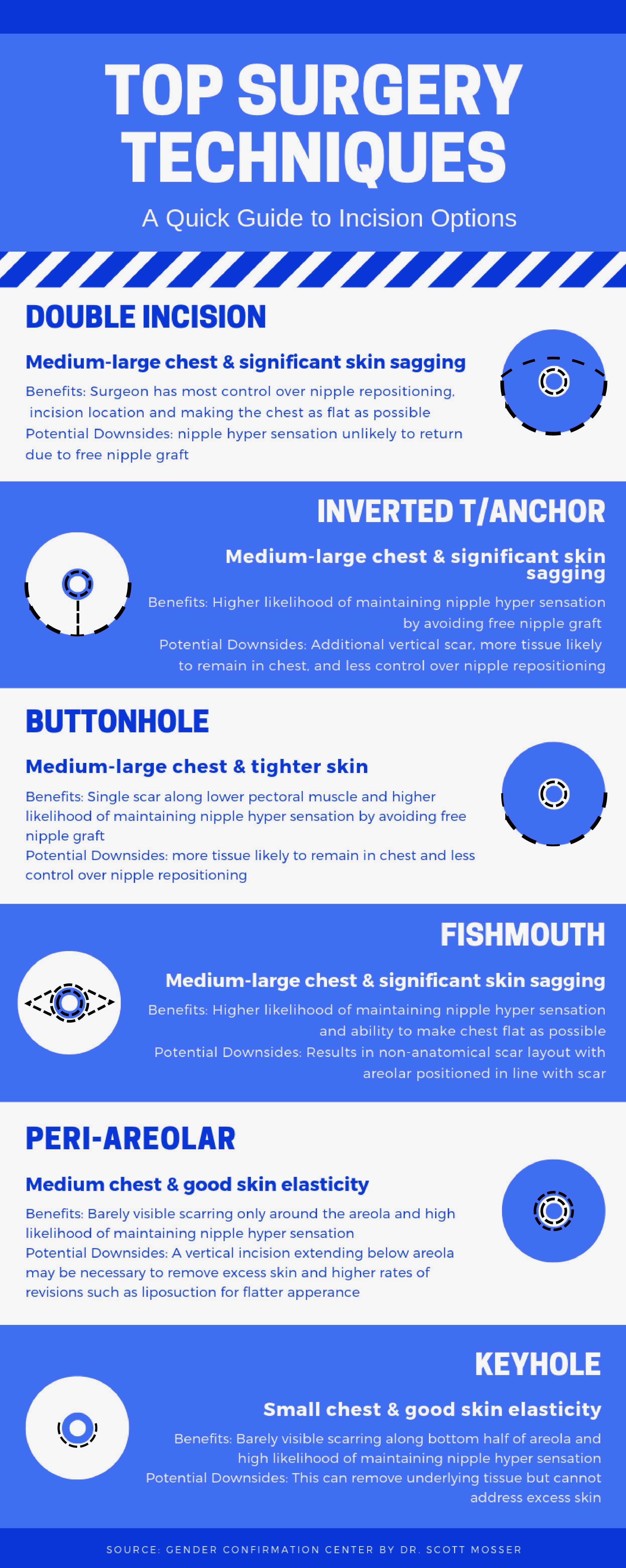

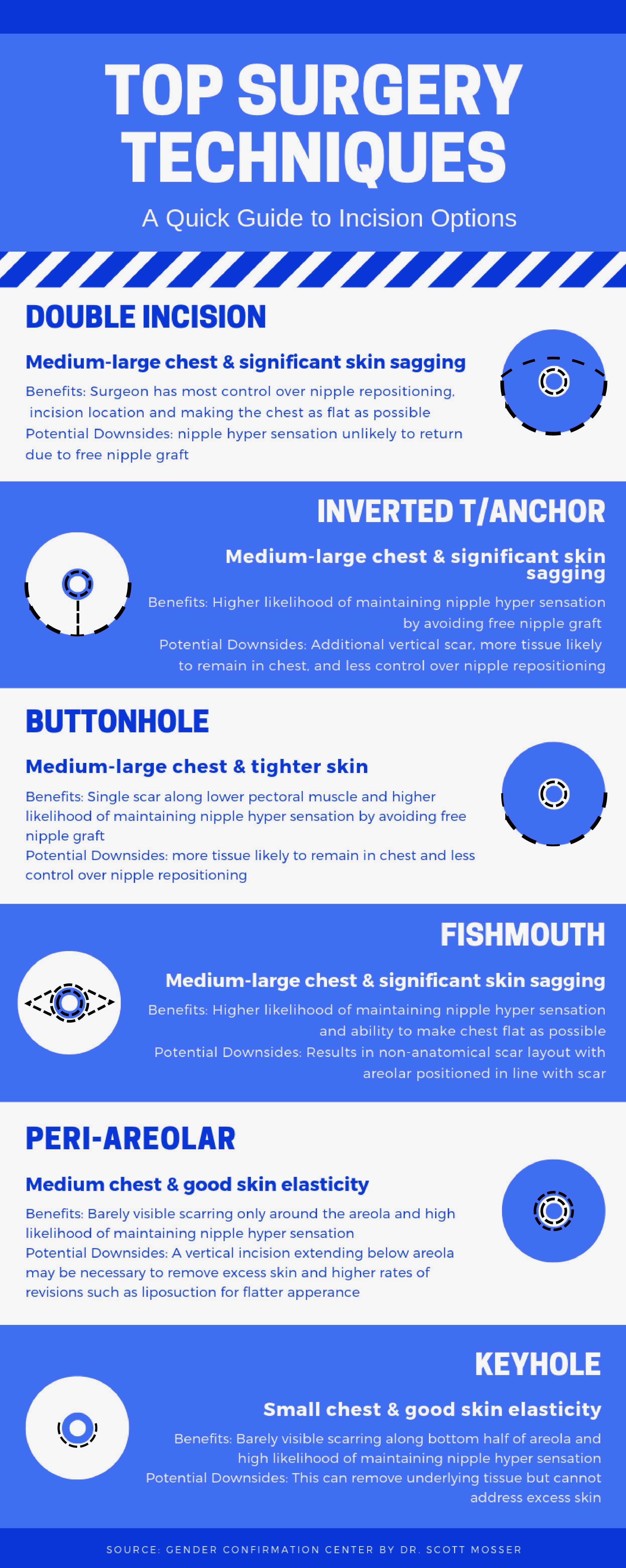

Not only is the environment the surgeon provides important, but the type of procedures offered as well.

Each operation has variation that can make the chest look more or less masculine and results in different scarring.

Some surgeons will only perform a double incision, which results in a hypermasculine appearance that fits well within the gender binary. Some patients prefer a peri result, "where there's no scars and they want to keep some breast tissue because having a totally flat chest might make them feel dysphoric," Rose said. "And a lot of patients don't want to keep their nipples and want to have the option of getting them tattooed on later or having prosthetics."

Dr. Mosser offers all incision types as a more comprehensive model of inclusivity, but this is uncommon due to both a lack of surgeons trained in all methods and to surgeon's personal aversion to certain surgical results.

The surgery O'Handley is scheduled to get falls under the FTN umbrella, or "Female to Nonbinary or Gender Neutral or Neutrois." Boyask, Monsour and Arnon all went with the double incision technique.

Despite the intense policing of access to and types of top surgery available, the procedure itself is "very safe with low risks," Kryger said. "It's 100 percent less risky than implants which require replacements and can rupture, and especially if you're getting a full mastectomy because then you're not risking breast cancer either."

With minimal risk involved in breast removal as compared to breast augmentation, the reason for providers' reticence becomes especially clear.

"Providers have a lot of fear and stigma around permanent body modifications and worry someone is making a mistake, which is of course not their place to decide," Rose said. "I think a lot of surgeons—or the medical community in the world at large—don't realize that there are nonbinary transfeminine folks or why they'd want this."

Post-Op

M

edical providers who refuse to provide gender-affirming care out of fear the patient will regret it are not totally unfounded. "There is no way to without any certainty at all know what somebody is or isn't going to regret or should or shouldn't have," said Olson-Kennedy. And he's had clients who regret surgery.

The problem arises when mental health providers who wrote a letter for a client that regretted their surgery becomes paralyzed thinking this could happen with future patients. "Most medical interventions are based on a model of balancing the the benefits with the potential risks of what happens right now compared to what does it look like years from now," Olson-Kennedy said. "Gender-related care is one of the few places that we veer from that very standardized, well accepted model of intervention and care because we still evaluate and look at gender as a choice, and we still look at it through pathology."

And just as the rest of our bodies shift as we age, so to can gender identity and expression.

"I don't hold anybody to any promises," said Hopwood. "People are where they are because that's what they can tolerate at that moment, and that may stay the same or it could shift." Monsour, for example, had no intention of going on Testosterone until a few months after deciding to get top surgery. After watching YouTube videos on the subject and learning more about its potential effects, such as their voice dropping, Monsour decided to go on T just for a short period before and after their top surgery.

People are where they are because it's what they can tolerate at that moment

Monsour's choice, like the decision to remove breasts, should not come as such a surprise. Gender norms are constantly in flux. But because society remains largely unconscious to the social-historical factors that define these shifts, such as the 1950's fixation on large breasts and motherhood as synonymous with femininity, these norms are understood as natural.

When confronted with the illegitimacy of this perceived naturalness, society often reacts with violence. This violence can be structural, such as norms and institutional policies that limit access to resources like health care and job opportunities; it can be interpersonal, such as verbal harassment and physical violence; and it can be individual, such as the feelings people have about themselves based on experiences of violence and how those feelings shape future behavior.

Current examples of structural violence can be found via GLADD's Trump Accountability Project which chronicles each attack the Trump administration has made against the LGBTQ community since entering office, now totally over 100. This includes an October 2018 proposition by the Department of Health and Human Services to change the legal definition of sex under Title IX, which would require individuals to identity according to sex assigned at birth and would remove nondiscrimination protections for transgender, nonbinary and intersex people.

Structural violence gives permission to members of society to perpetrate interpersonal violence, a trend that is clearly reflected in hate crime reporting data. Focusing in on what is often assumed to be the liberal, LGBTQ friendly Los Angeles County, data from crime records records show hate crime reports were up 11 percent in 2017. Over 30 percent of these crimes targeted LGBTQ individuals, even though the LGBTQ population makes up only 4.5 percent of the total population.

Further dividing the data into property crimes and violent crimes shows that property crimes, such as arson or vandalism, are most commonly seen in religiously motivated hate crimes. Conversely, hate crimes targeting victims based on race, gender or sexual orientation are most likely to be violent in nature. In L.A. County, transgender individuals experience the greatest threat of bodily harm: over 95 percent of hate crimes motivated by transgender bias in the past six years were violent.

Violence motivated by anti-transgender bias in Los Angeles parallels national trends. Advocacy organizations including the Human Rights Campaign report that a nationwide increase in violence motivated by anti-transgender bias is interconnected to an increase in anti-transgender laws. The National Conference of State Legislatures reported that in 2017, 16 states considered bathroom bills—which aim to limit who can use gender-specific public restrooms—and 14 states considered laws limiting transgender rights in schools.

In this environment, the decision by anyone identifying outside strict gender norms to become invisible would make sense. Visibility leaves people vulnerable to discrimination and violence. Monsour, Arnon and Boyask, however, have had the opposite reaction.

"For me, I felt like sharing my experience with top surgery was helping a lot of other people because I get a lot of really good feedback from people commenting on videos and saying that it was helpful to them," Monsour said about their decision to vlog their experience on YouTube. "But also in kind of a more personal note, it's helped me feel more like being trans and transitioning are are not things that I should feel ashamed about or that I should feel like I have to hide from people."

Monsour combats that shame and fear through talking about it, especially with people who are uncomfortable with the topic. "Over time, talking about it makes people feel less uncomfortable and more willing to learn more," they said.

Boyask, who has had his scars for nearly a decade now, has experienced a drastic change in his feelings about visibility over the years. "They've always been battle scars to me, but at the same time they were something that I wanted to make fade as quickly as possible for a long time," he said. Stealth for our entire college career, Boyask began living "loudly and proudly trans" around two years ago.

"There's never been a time in my life where I was ashamed to be trans; I was always afraid to be trans, and those are very different things," he explained.

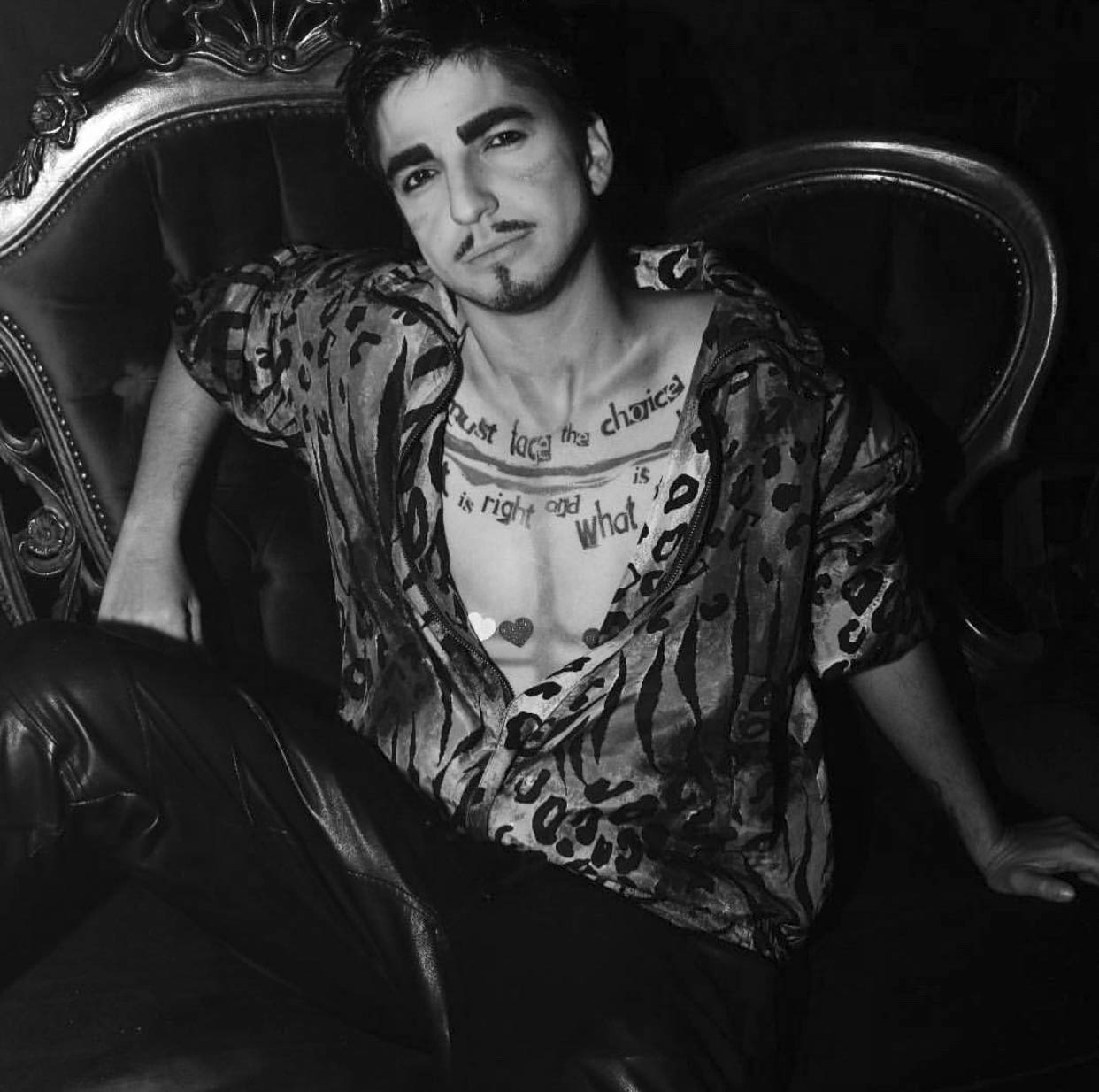

Photo Source: Jason Boyask

A specific moment Boyask cites as pivotal in his visibility happen New York City Pride 2018. While walking in the parade with the skincare brand Kiehls, every 15 minutes or so he would look at the crowd and another trans person proudly showing off brand new top surgery scars. "Every time I would just feel myself tugging at my shirt, and showing my scars was the only way that I have to say 'I see you and we are the same.'" Halfway through the parade, Boyask pulled his shirt over his head so it was sitting around his neck, framing his scars. "This was a very pivotal moment in the way I think about my scars," he explained. "I'm taking off my shirt specifically because I want a other trans people to—and people in general—to see that I have scars, and that's been a thing moving forward."

Arnon was hesitant at first to take off their shirt in public. "I lived 26 years with boobs and I know how society says I'm supposed to be," they said. Through drag, Arnon was able to undo some of this conditioning and become more visible, putting pink and blue glitter on their top surgery scars for their first post-surgery drag show. Performing to "How Far I'll Go" from the Moana soundtrack, Arnon kept a trench coat on until the very end before turning around to reveal their scars to the audience.

"I wanted to show not only myself but my community that I love this body. I made this body. I chose these scars. They are a part of me."

Arnon could choose to cover their scars with makeup, but instead decorates them each performance as a "conscious choice to make them visible." Most of Arnon's drag is political and highlights the way society treats women, trans and nonbinary people. "When people talk about trans bodies, they talk about how weird and unnatural they are, saying things like 'you're not supposed to be like that.'"

During one of Arnon's favorite performances at the Tel Aviv Fest Drag Star Search, they performed to Imagine Dragons' Bad Liar, popping pink and blue powder filled balloons on their chest before tearing of their shirt to reveal decorated scars. Following their performance, a judge thanked Arnon for being able to shed their costume and show the audience their true, beautiful self.

Photo Source: Lee Arnon/King Snow

"Drag is the art that makes us be ourselves," Arnon responded. "When we choose to do drag, and we choose to go the way the world could see us on a daily basis, it's a protest. A protest for the things I see every day because of my gender and because of my identity."

Conclusion

A

s the number of people pursuing top surgery from across the gender spectrum continues to grow, both the health care system and society as a whole will be forced to reconsider discriminatory stances barring people from living an authentic identity.

"I do not think of medicine as in any way benevolent," LaFleur said. "I do think that there's more of a pressure on doctors now, especially since the passage of the Affordable Care Act, when doctors started getting interested in offering gender affirming surgeries because they can make money from it."

This pressure to provide gender affirming care is also coming from a rapidly shifting culture, one in which expressing one's authentic gender or sexual identity is in tension with conservative values narrowly defining gender and relationships as man and woman. This culture shift is having an impact on every sector, as documented annually in the Human Rights Campaign Foundation's Corporate Equality Index. In 2019, 571 major businesses earned a top score of 100 percent and the distinction of "Best Places to Work for LGBTQ Equality." When the reports began in 2002, only 13 companies made that list.

"I do think that it's going to take 10 to 15 years before society can accept nonbinary people assigned female at birth can have dysphoria and not identify as male and still need to have chest reconstruction," Hopwood said. "People talk about a spectrum—I talk more about a gender universe as three-dimensional space where there's people everywhere."

The key to the cis women of past decades reclaiming their breasts and in turn their sexuality then necessarily requires inclusion of people with breasts from across the gender spectrum.

While this universe can be hard for people to comprehend at first, more and more research is coming out about the negative implications of socialized gender norms. The Global Early Adolescent Study, which studies how gender socialization for those ages 10 to 14 occurs around the world, found that with adolescence comes a common set of rigidly enforced gender expectations associated with increased lifelong risks of physical and mental health. Girls are seen as "potential targets" once puberty hits, and there is a contrast between a demand for modesty and hypersexualization. And with that comes the ever popular phrase, "cover up."

People removing their breasts, and especially femme presenting people removing their breasts, disrupt this global system of harmful gender norms in a very visible way. How can you force someone to cover up what doesn't exist?

On April 26, the day of O'Handley's surgery, her GoFundMe reached its goal.

Asking those who she's made an impression on to help support her in the "biggest milestone" of her life so far, O'Handley acknowledges this news would come as a surprise to many. "When it comes down to it, the way I identify and the way my body takes up space doesn't, and has never really, been a good match," she wrote.

"So here we are, at the forefront of new beginnings, where I can embrace myself in a way I'd never imagine possible."