Jefferson's current community, comprised of dedicated faculty and motivated students, is only partially responsible for the school's success.

"There is magic to good pedagogy, but it only goes so far," said Samuel Abrams, director of the National Center for the Study of Privatization in Education at Columbia University. "The underlying factors, including insufficient family support, insufficient medical attention, poverty, neighborhood deficits, the level of educational attainment of the parents or parent, explain much more of the academic achievement of students."

According to the US Census Bureau's 2017 estimates, roughly 60 percent of those 25 years and over in South Central LA have graduated high school and just above 6 percent have a Bachelor's degree or higher.

The demographics of Jefferson's students put them at a disadvantage in terms of potential educational achievement.

With a reported graduation rate of 98 percent, compared to LAUSD's rate of 76 percent according to the state's Department of Education, the question then arises as to just how Jefferson's students beat the odds.

And, perhaps more significantly, is this success sustainable in the current American public school climate?

To begin to understand the spike in graduation rates, Abrams argued "the attribution component is critical."

Abrams pointed to the concept of the peer group effect, which posits that difficult students distract classmates and disrupt educational instruction.

A former teacher of 18 years, Abrams described, "if I had four difficult kids, I could handle it. If I had eight difficult kids, it wasn't twice as hard: it was exponentially more difficult because you get a chain reaction."

When Jefferson's principal Agustin Gonzalez arrived in 2015, his first priority in addition to transforming the faculty was to identify troubled students.

"We had to make a serious decision with every single student and start scrutinizing why they're here," Gonzalez said. "We have to build resiliency with some, we have to build hope with others, and quite frankly, with others, we have to get rid of."

For those students in the last category, who are either counseled out or expelled, Gonzalez believes their actions speak for themselves.

"They've caused so much drama and impacted the instructional program that we can't afford to have them continue, because it's going to take away from the true work: the instructional component," he explained.

This, Abrams argued, is key to understanding much of the student's increased motivation.

There's not a huge difference between 900 and 700 students, unless you're taking into consideration that those 200 were difficult kids. Then you're talking about a totally different school," Abrams said.

Difficult students, many of whom are a product of factors outside their own control, are subsequently ostracized from this no excuses model of education. Ensuring the success of well-behaved students inevitably targets already disadvantaged youth.

Compounding this problem, some experts argue, is privatization and school choice.

The LAUSD Board of Education adopted the Public School Choice resolution in 2009, offering parents options including open enrollment, charter schools and magnet schools. The district currently has the largest number of charter schools in the country attended by nearly one in four students, according to LAUSD opensource data.

This push stems from a "justified frustration with public school districts," Abrams said.

"Parents' best instincts will very logically say, 'I want the best for my kids,'" said William Mathis, managing director of the National Education Policy Center at the University of Colorado Boulder.

In reality, what researchers including Abrams and Mathis are finding, is that school privatization and choice are exacerbating both economic and racial divides and the achievement gap.

When asked if school choice leads to a better quality or more equitable education for all students, Mathis answered with an unequivocal, "No."

Referring to the disparity in academic performance between groups of students, the achievement gap is found in metrics such as standardized test scores, dropout rates, grades and college-going and college-completion rates.

As for charter schools, a report from the Center for Cities and Schools at the University of California Berkeley found they cluster disproportionately in LA's lower-income, Latino and black neighborhoods. Additionally, the report linked charter openings to an increase in property value and the proportion of white residents, as well as a decrease in public school enrollment.

However, the solution to this dilemma, experts like Mathis argue, cannot be found within schools.

"Unless you deal with the social environment of this country, we're going to have segregated schools," Mathis said. "And the segregation problem we have in this nation is not because the schools are failing. The schools are merely the reflection of a cultural pattern."

"It's not healthy for democracy," he added.

It is within this climate that Jefferson, a school whose population is nearly 99 percent low-income students of color, is fighting to give students a fair chance.

National Education Policy Center associate director Michelle Renee Valladares describes this goal as emblematic of an equity-minded school.

According to Valladares, there are three main components to an equity-minded school. Namely, that every student has the resources necessary to be prepared for college, a meaningful career, and civil life.

Because "we live in an inequitable society," Valladares explained that the ways in which schools provide an equitable education will change depending on the its location and the student demographics. "For some schools, that might mean having health care on sight for students," she said.

Valladares, who previously led the Time for Equity Indicators Project at Brown University's Annenberg Institute for School Reform, said many of Jefferson's services and policies align with key equity indicators.

The first step on the way to equity is, unsurprisingly, creating the conditions for its success. This includes the establishment of norms, values and relationships that foster student development and inclusivity. In other words, the faculty's push to build a Jefferson community.

Equity indicators further measure access to more, and more efficiently used, educational time in addition to support services such as special education, translators and English Second Language instructors, all of which Jefferson offers.

Students can receive after school tutoring from teachers in each subject area and through partnerships with universities such as the University of California Los Angeles. There are seven periods in a day instead of six, so students are able to repeat failed classes during the school day, and they can also make up credits during Saturday school or summer school.

A focus on relationships between students and faculty as well as partnerships with the larger community is another essential component of equity. As are wellness services such as health care, which Jefferson has covered as one of LAUSD's 15 campus health care centers for students and families.

"We're a father, a mother, a therapist, a mentor, a grocery store sometimes, a clothing store sometimes to these kids," Gonzalez said. "You truly, to work in this school, you truly have to treat these kids as if they were your own."

"Having the resources kids need goes well and beyond what we think of as a curriculum or a safe school building," Valladares said. "It's high quality teachers and all of that, plus these wrap around supports."

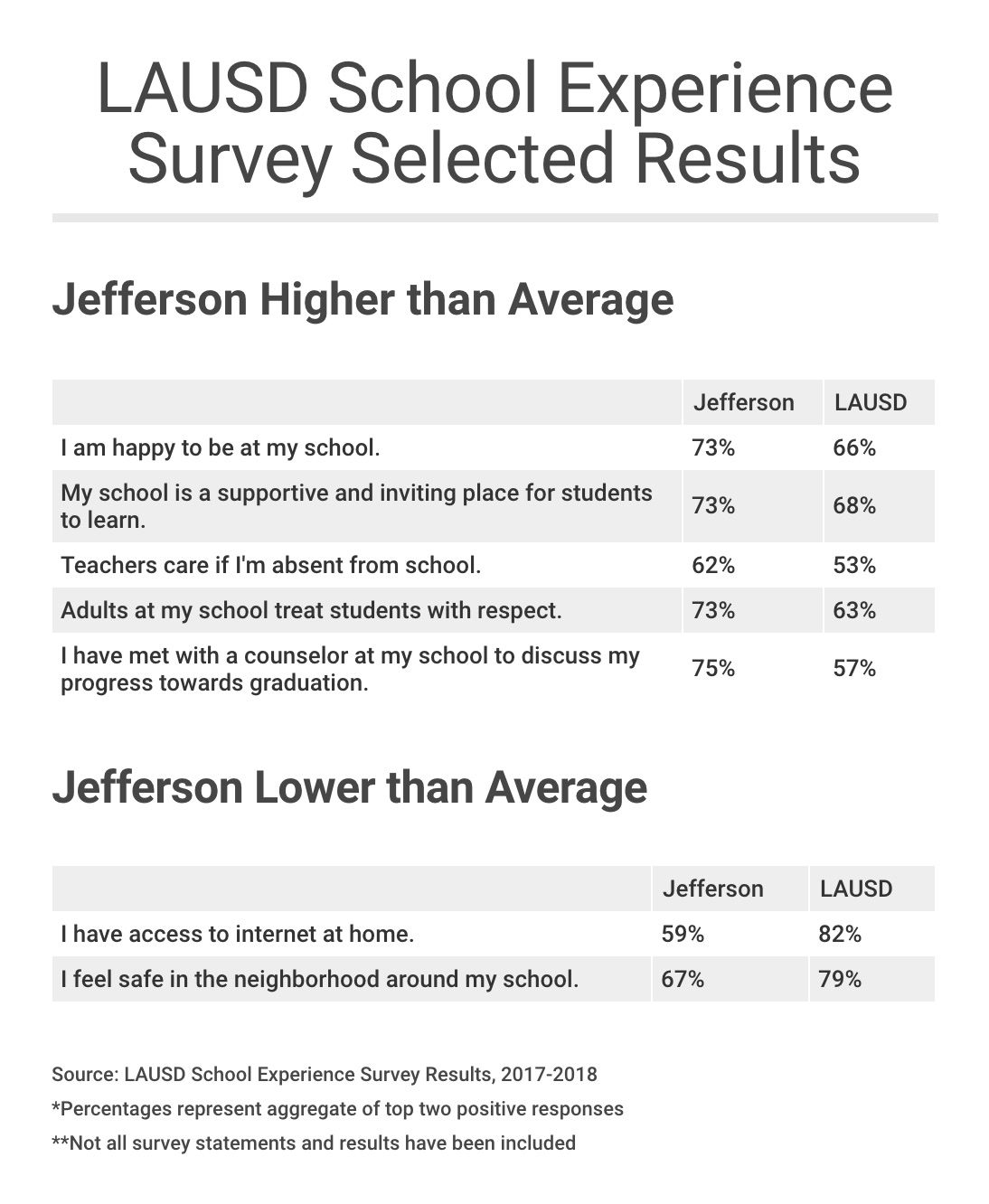

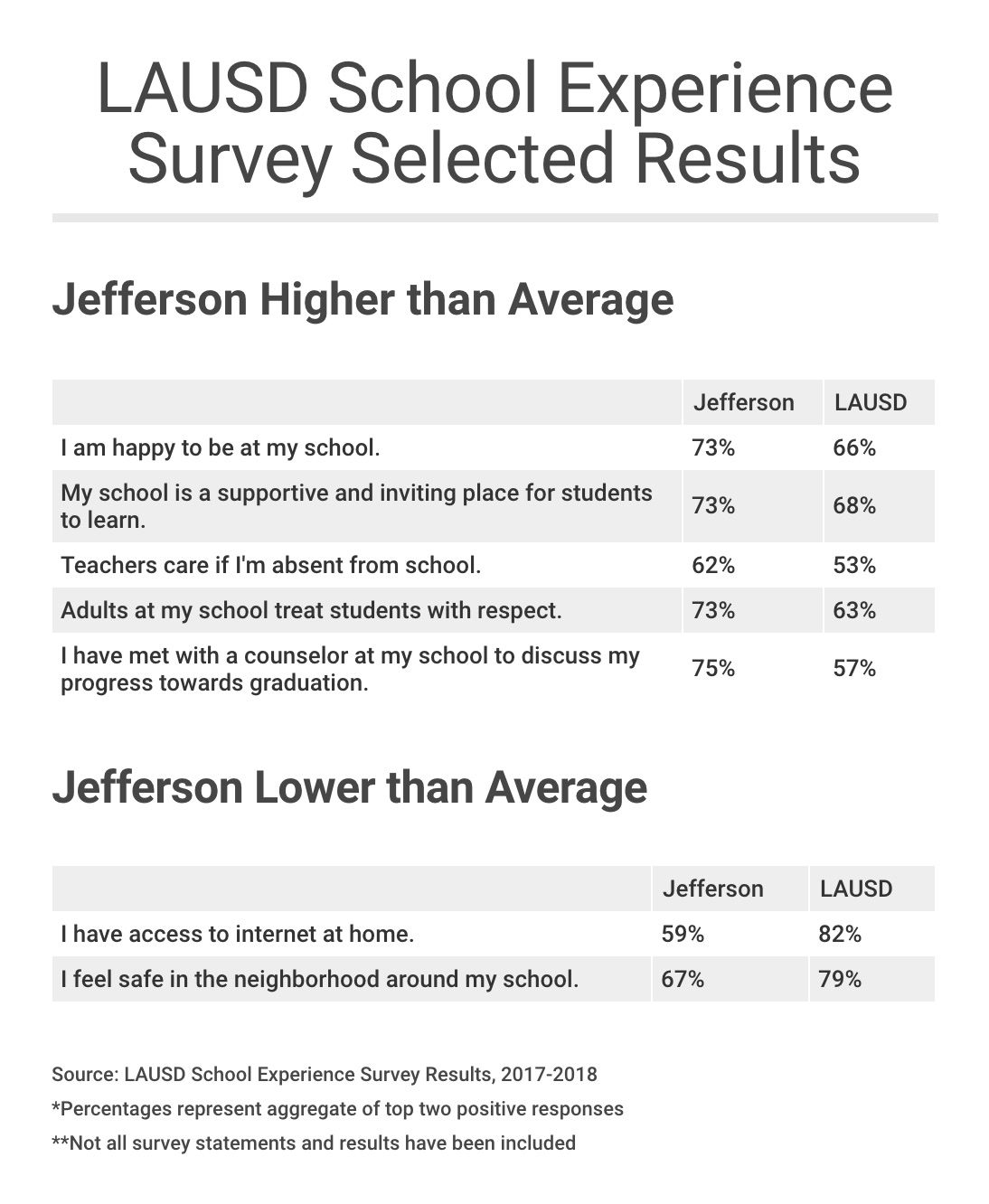

Recent data backs this up. In LAUSD's annual School Experience Survey, which asks respondents to select their answer on a scale from "No, Never / Strongly Disagree" to "Yes, Always / Strongly Agree," 57 percent of Jefferson's students and 77 percent of the faculty responded. In comparing the aggregate percentage of the top two positive responses, Jefferson performs better than the LAUSD average a majority of the time.

Both Valladares and Gonzalez looked to the movie Field of Dreams to drive their messages home. For Valladares, the message is "first you have to build it." Before looking to standardized test scores or college acceptance rates, schools need to measure if what they are building is actually equitable.

"No business opens its doors today and makes a million dollars. They have five years of start ups," Valladares said.

For Gonzalez, this reference is less about metrics and more about a vision.

"As corny as Field of Dreams sounds, if you build it they will come. It's as simple as that," he said. "You got to put belief systems, values in there that make people believe."

Gonzalez's eyes glaze over and he takes a deep breath. "Maybe that's what my role is," he said.

"Come to our family and believe that you can do it, and we'll make it happen."