Biology teacher Ava Behr. Source: Mikayla Bean

By Mikayla Bean

"It was about 30 adults and myself in a line, and on one side we had about 100 students, and on the other side we had another 100 students that were just jawing on each other."

Agustin Gonzalez arrived as the new principal of Thomas Jefferson Senior High School on September 8, 2015 on the coattails of a riot. Three weeks later, he found himself in the midst of another.

"Honestly, I was embarrassed," he said. "I saw it as a lack of respect and a lack of leadership."

Called in for the job by Los Angeles Unified School District Superintendent Ramon C. Cortines, Gonzalez had already built a reputation as a transformer. While he's been called a "fixer" and a "cleaner," Gonzalez prefers the title "coach."

And as Jefferson's new head coach, Gonzalez quickly began assemblinghis team.

In this first phase, he created a "sense of urgency" by reassigning teachers and support staff he believed were not in alignment with Jefferson's new direction.

The school, which opened its doors in 1916, has undergone rapid change over the past 15 years. "A lot of things happened that people felt resentful about," Gonzalez explained.

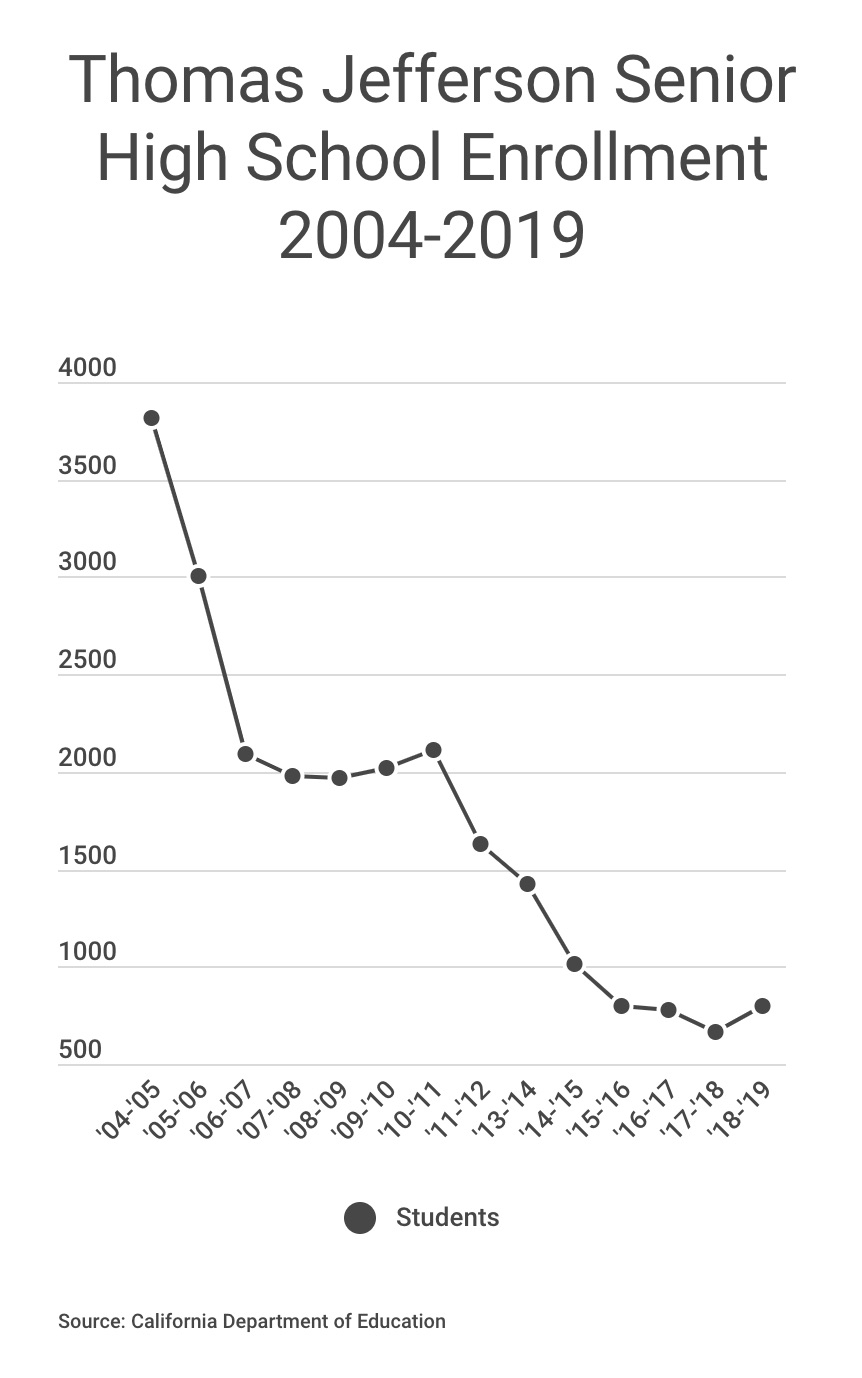

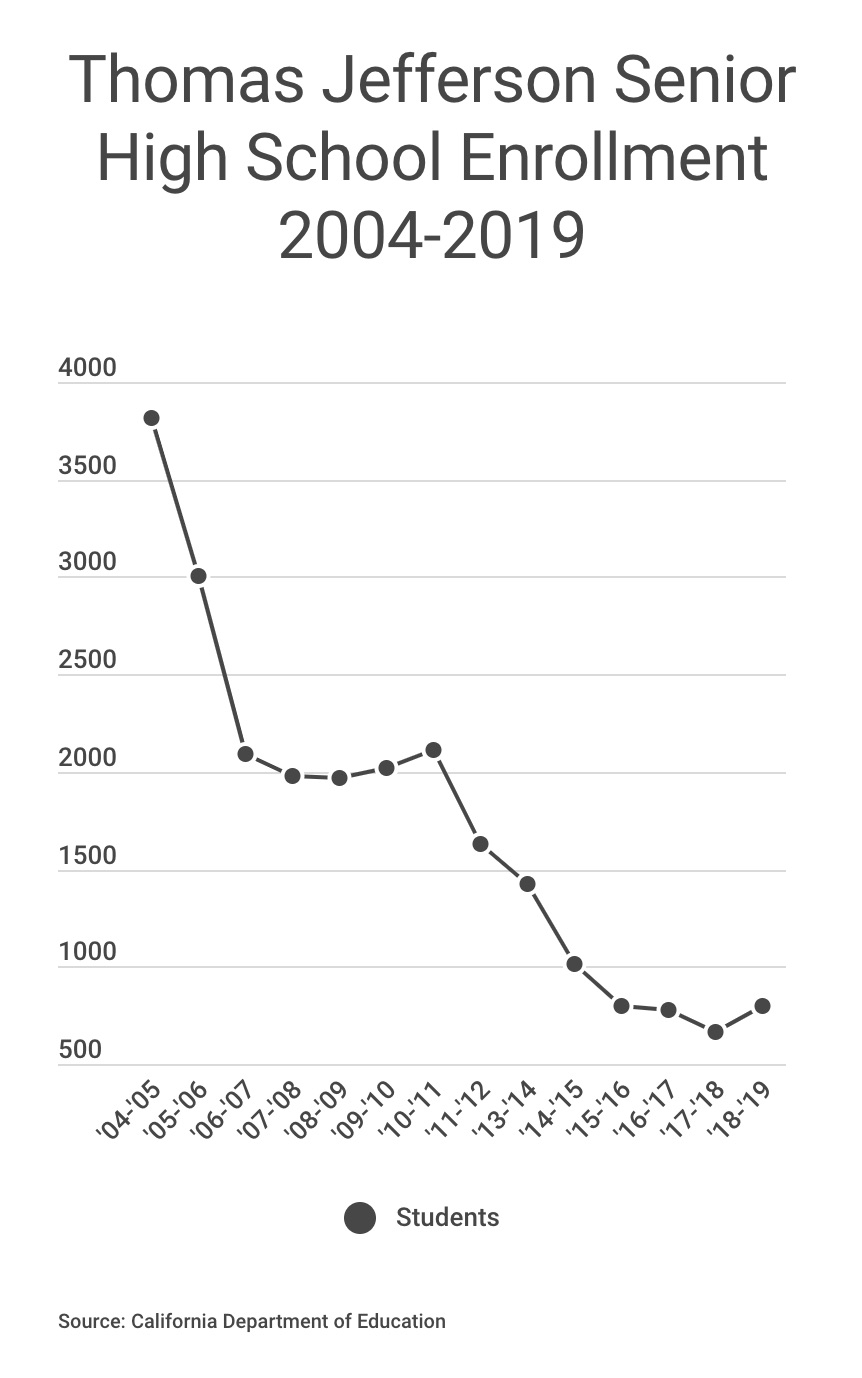

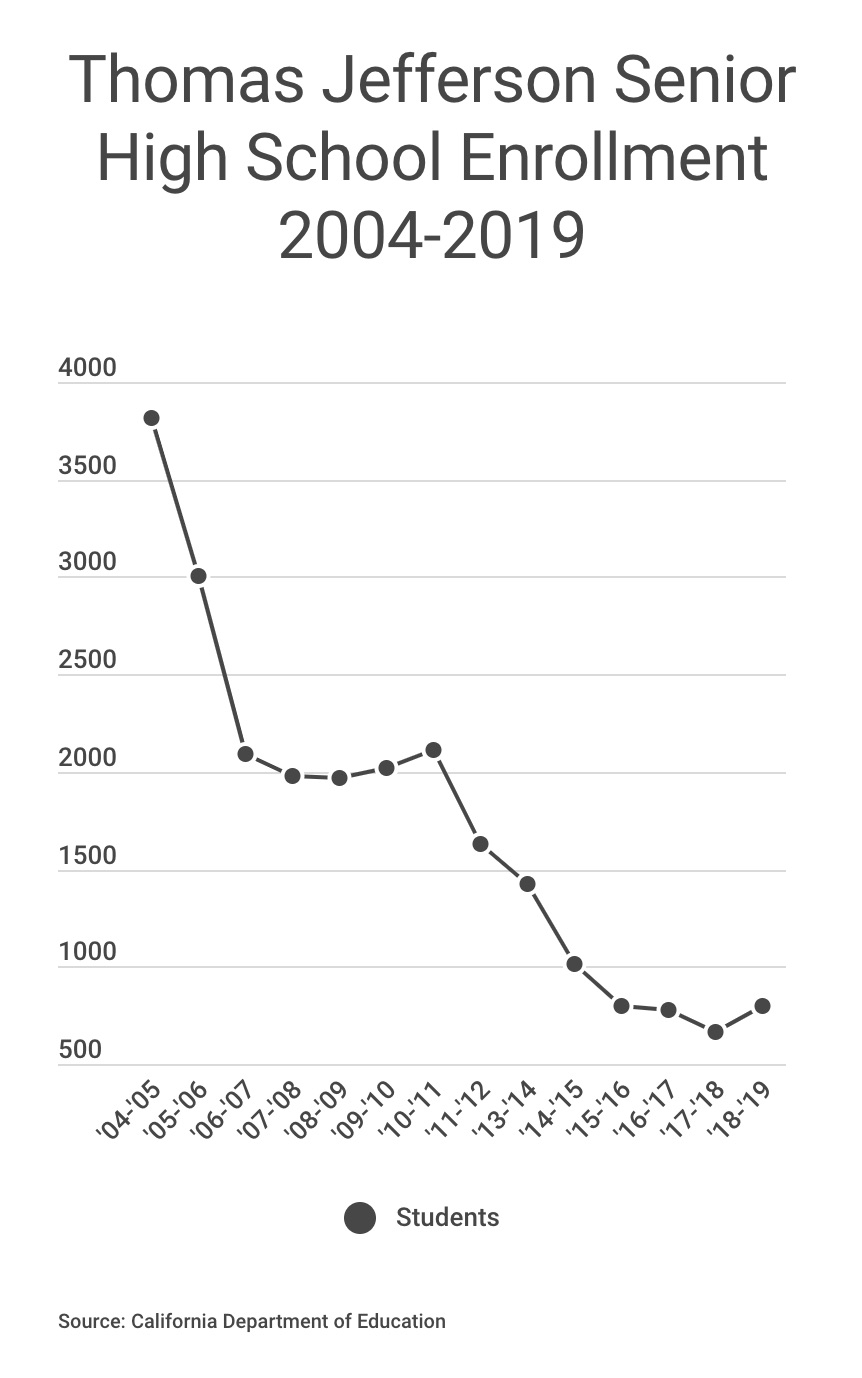

In the spring of 2005, Jefferson was the scene of three riots. With a lack of resources and a population of nearly 4,000 students, the South Central LA high school became a national example of the country's inequitable urban education.

Racial tension exacerbated by gang influence led to brawls involving hundreds of students, and police in riot gear armed with tear gas were sent in to diffuse the situation.

Click to enlarge

"All that anybody knows, is that Jefferson cannot go another year, let alone another decade, failing so many kids," said NPR reporter Claudio Sanchez following the riots.

Three year's later, the school's population had dropped by nearly 50 percent.

By the time Gonzalez arrived, there were only 797 students.

To stem the outflow of students, Gonzalez leaned on his staff, bolstering the remaining veteran faculty with young hires.

"They're not jaded by our profession or by the world," he explained. "I like to bring young people in and see how their passion can transfer over to teaching or supporting our kids."

Gonzalez's goal? To build a community, a "family," where students have pride in the school, each other, and themselves.

"We were very careful in the types of people we brought into the campus," said Brian Artica, whose official title is Jefferson's problem solving data coordinator. "I can think about each of the new hires and give you at least three things that they've brought to the campus."

Artica, who has worked at the site for over a decade, believes the investment from seasoned faculty coupled with the reinvigorating "freshness" of new teachers has enabled Jefferson to progress.

"If we are stagnant, then what do we expect of our students," Artica asked. "We're asking them to grow as humans, shouldn't we as well?"

Brian Artica, Problem Solving Data Coordinator. Source:Alexandrea Bell

A main challenge to this growth, both for the students and faculty, came from outside misperceptions.

"When I tell people from outside the community I'm from Jefferson, they say things like 'Wow, but you speak so well,'" said Perla Sotto, a Jefferson senior. Sotto believes the stereotypes about her school and the larger South Central community put students at a disadvantage.

"I feel like we have to work two times harder," Sotto continued. "A lot of people here are driven to make something of themselves because we recognize that we don't get everything we deserve."

This drive to prove stereotypes wrong, coupled with support from her teachers and counselors, is what Sotto said pushed her to transform from a freshman failing most of her classes into the president of her senior class.

Many of Sotto's peers share her experience.

"They thought I wasn't going to do it, and I proved everybody wrong," said junior Jaylen Kelley. Before this fall, Kelley was failing nearly all of his classes. Now he's on his way to a 3.0 GPA.

Kelley was planning on dropping out before teachers and administrators intervened.

"Jaylen's my boy," said Gonzalez. "He's going to make me cry when I see him graduate on that stage."

They thought I wasn't going to do it, and I proved everybody wrong

Gonzalez played basketball with Kelley, who was ineligible to participate in sports due to his grades, to give him something to work towards. Kelley described how his teachers gave him the confidence to ask for help and worked together to help him turn assignments in on time.

"People provided hope for him. That's what we do:provide hope," Gonzalez said.

For many students who enter Jefferson, this personalized attention and support is what they attribute their success to.

Sotto arrived at Jefferson at the end of her freshman year unmotivated to work, having transferred from Alexander Hamilton High School. At Hamilton, Sotto recalled not knowing who her principal was, and said she was not being pushed to better her grades.

The contrast between her previous high school and Jefferson was immediate.

"Within the first two days that I transferred here, Mr. Gonzalez already knew who I was," Sotto said. Counselors called her into the office to plan how she could better her grades, listening to Sotto's needs and pairing her with teacher's they thought could support her best.

Like Sotto, Julio Martinez came to Jefferson unmotivated to learn. Martinez immigrated from Mexico in eighth grade and began hanging around with gang members. At the start of his freshman year in 2015, Martinez was involved with the riots. His mother then sent him to live with his godparents in Salt Lake City, Utah for a year in hopes of changing his behavior.

That's what we do: provide hope

When Martinez returned to Jefferson as a sophomore, the support he received did just that.

"My mom always told me I have an angel above me guiding me through a good path," he said. "If I can't do it myself, people help me from this school — counselors, teachers, all of them."

This personalized, dedicated support stems from the faculty's acute awareness of the impact external factors have on students' academic potential.

History teacher Dr. Aissa Riley, who has worked at Jefferson for 15 years, argues understanding students' personal struggles is a job requirement.

"At the Jefferson family we have a saying: it's so hard to be a Demo," said Riley, referencing Jefferson's mascot, the Democrats. Whether students are dealing with the stigma associated with Jefferson and South Central LA, poverty, homelessness, the foster care system or gang violence, "everyone has some sort of extra need we have to take into account."

Rather than allow these disadvantages to stagnate her students, Riley creates space in her class for them to voice and connect over shared experiences. In Riley's experience, these facilitated conversations strengthen the desired sense of community and foster accountability.

"Not all of our students have a home life where they have someone who's giving them guidance, and so that's what we're all here for," Riley said. "Even their classmates will check them and tell them, 'why weren't you here? Why didn't you do this?'"

Dr. Aissa Riley, History Teacher. Source: Alexandrea Bell

Biology teacher Ava Behr, who began working at Jefferson last year after two decades at a high school in the Valley, described a shift in her perception of what is and is not appropriate to talk to students about.

"I'm coming in like, 'let's learn about biology!' Thinking we're all just here to learn science and learn to love it. No. It's a lot more complicated than that," Behr said.

As one of the only white individuals at Jefferson, Behr has put concerted effort into understanding the impact race has on building the types of relationships required to motivate academic success in her students.

Within the last year, she bought three books on the topic and met monthly with LAUSD's Title III coordinator, a position targeted to benefit limited English proficiency children and immigrant youth.

The extra hours teachers like Riley and Behr spend supporting their students well beyond textbook instruction have enabled current students to feel confident in their academic potential.

"When teachers are supporting students, students are more motivated to learn," Sotto said.

Teachers capitalize on this motivation and renewed sense of potential to push the idea of college. Jefferson's college center guides students through each step of the college application process, including filing for financial aid. And it's not only current students who utilize these resources.

"You'll see a lot of past students who are still getting help with filing a Fafsa," Riley said.

Edwin Pedro, a 2015 Jefferson graduate who now attends the University of Southern California, had no intention of pursuing higher education when he entered high school. "Dr. Riley pushed the idea of college into my head," he said.

"Applying to college was actually fun," Pedro continued. Researching schools and imagining himself in new cities expanded the framework through which he viewed future opportunities.

With a consistent push from Riley, Pedro began working with a college counselor who encouraged him to apply for the Gates Millenium Scholarship, which provides full financial support from undergraduate through doctoral programs for outstanding students of color. Initially resistant to completing the eight essay application, Pedro said the pressure from Riley and the school's counselor eventually convinced him.

"Then the news came that I got the scholarship," Pedro said.

Thomas Jefferson Senior High School College Center. Source: Mikayla Bean

Looking back, Pedro said he would not have made it to college without that support. "I'm grateful for my teachers, because they actually made me realize there's more opportunities than just here."

A key component to the success of Jefferson's community relies on alumni returning to mentor and tutor current students.

"I really try and push on the students is that they need to come back," Riley said. "In general, in our community, we consider making it by getting out of our community, and that doesn't help us when everyone we see are people that have struggled to get out and have struggled to be successful but we don't see the ones that have been successful."

This message seems to be sticking.

Bryan Zamora, a senior ranked at the top of his class, hopes to go to Stanford University and study computer science. "I decided to study computer science, because since I was a kid I had the dream of making the world better," he said. Zamora hopes to invest the money he makes developing technology to provide scholarships to future students in his community.

I'm grateful for my teachers, because they actually made me realize there's more opportunities than just here

Similarly, Sotto plans to study political science so she can return to the community and teach her neighbors about their legal rights. "One of my main goals is to come back and contribute to this community, especially at Jefferson," she said. "We really are our own little family."

When asked to reflect on how he would define Jefferson's community after four years at the helm, a single word came to Gonzalez's mind: "Resilient."

"You've got this representation of students that show South Central is not just a setting for a gangster movie," Artica added. "It's a place where people live and work and enjoy life. And you have opportunity and possibility with the right support."

Zamora is hopeful the Jefferson community, his community, will create long lasting change for the school and South Central as a whole.

"I believe if we all put something on the table, we can make a dinner. Right?"