The 58-year-old performing arts technician co-founded the Los Angeles-based polytheistic group Thiasos Phoibos, which uses the Greek letters ΘΙΑΣΟΣ ΦΟΙΒΟΣ.

Cameron founded the group five years ago after being introduced to the tradition through his friends. “Up until then, I didn’t know it existed as a worship option,” he said.

Cameron’s group has 15 members who regularly attend events and prayers, but the Facebook group it maintains has almost 160 members.

Local U.S. Hellenic chapters do not report to any national or international body. Worship is based on word of mouth traditions and classic ancient literature, says Cameron.

The Hellenes of Dodecatheon, a loose organizational group, reports around 2,000 followers in the U.S., but 100,000 believers use the traditions as a baseline for their religious practices.

Hellenism is a mainly domestic religion in which prayers and offerings are given in the home. There are designated holidays for different gods, but much of the worship is a guessing game based on scholarly interpretations of ancient text.

“As you can imagine, it’s really hard to find a Hellenic calendar,” Cameron said.

The neo-Pagan movement stems from ancient Greek mythology that centers on religion, philosophy and tradition. Its contemporary version arose in Greece as a way to diminish the power of the Greek Orthodox Church, according to the Archeology Institute of America.

The Supreme Council of Ethnic Hellenes Spring Equinox ritual at an ancient temple of Goddess Artemis in Peloponnese, Greece, in March 2016. Photo courtesy of Creative Commons

After scholars in the late 20th century debunked Wicca-based religions, people began to worship religions with ancient roots that they could trace, says Sabina Magliocco, a professor of anthropology and folklore at California State University, Northridge.

Because of the close ties between church and government in Greece, today “the practice of Hellenismos is actually illegal,” Magliocco said.

Hellenic worshippers have struggled to use historic landmarks such as the Temple of Zeus in Athens, for their worship because

of the Greek government’s opposition, which brings a lot of attention to

the Hellenismos, Magliocco said.

The Greek Orthodox Church has spoken against this form of religious revival, and has been aggressive towards Hellenismos, says Edward Butler, associate editor of “Walking the Worlds: a Biannual Journal of Polytheism and Spirit Work.”

“The church is implacably hostile, and has attempted to thwart any legal recognition of Hellenic polytheism,” he said.

This hostility was on display when the Rev. Efstathios Kollas, then president of the Association of Greek Clergymen told the BBC that Hellenic polytheists “are a handful of miserable resuscitators of a degenerate dead religion who wish to return to the monstrous dark delusions of the past.”

Other scholars say it’s a global movement toward personal fulfillment, disconnected from the Greek Orthodox Church.

“I believe that the polytheist revival, not just in Greece, but all around the world, is a phenomenon of the first importance spiritually and

intellectually,” Butler said. He studied polytheism a The New School for Social Research.

“These are individuals rediscovering a relationship with gods that have been proscribed, demonized, ridiculed, reduced to banalities,” he said.

Practice in the U.S. varies from person to person with many relying on scholars’ interpretations of ancient Greek texts since they don’t speak Greek.

“The question of rules is complicated, as even in antiquity polytheisms were highly diverse and had multiple forms of authority,” Butler explained.

Wendilyn Emrys, a second-year Mythological Studies student at Pacifica Graduate Institute in Carpinteria, Calif., is a member of Thiasos Phoibos.

As a child, she became ill and feverish and one night had an encounter with the goddess Athena. “She gently poured liquid into my mouth,” Emrys recalled saying it tasted more pure than any water she had ever drunk. “She stroked my head, and then faded out. My fever broke and I lived.”

Hellenic religious offerings can include a potluck dinner, like this one provided by Dean Cameron and other followers. They offer some food to the gods on an outdoor altar and then pray together over their meal. Photo courtesy of Dean CameronSince then, the 57 year old has been devoted to an American form of Hellenism. She is also involved with a Hellenic group dedicated to the Goddesses specifically.

This highly personalized practice is typical, even as groups try to open themselves to common rituals. Cameron, for example, holds prayers in his house, which includes the offering of oil, grain and meat to the gods. His fellow Hellenists pray as a group in English, but Cameron tries to add Greek when possible because, “it reminds us where we came from,” he said. Worshippers give offerings to the gods in the hopes of receiving blessings from them.

“Reciprocity is a very important part of Hellenism,” Cameron explained.

“I would save a Skittle, throw it into the bush and offer it to Dionysus,”he said. “Whatever they give you, you thank them.”

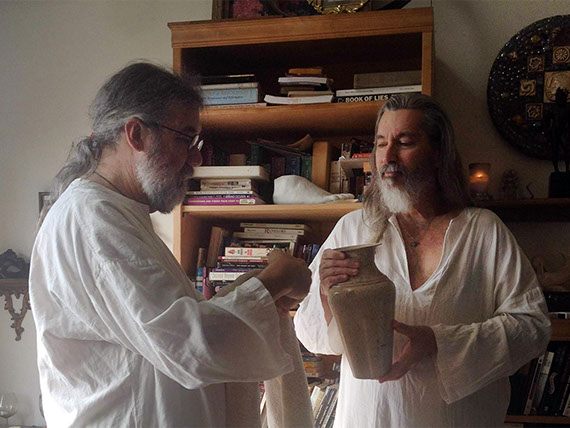

Dean Cameron, right, and partner Peter Thomas participate in domestic worship at their home in North Hollywood, Calif. They offer food and drinks to the 12 ancient Greek gods. Photo courtesy of Dean Cameron

To celebrate the winter solstice, Dean Cameron made an offering to Poseidon, the ancient Greek god of the sea.

In his North Hollywood backyard he placed a roast on the makeshift backyard altar that he calls the “Holy Hibachi.”

Then he returned indoors to eat a potluck feast with fellow Hellenic worshippers celebrating the solstice. Cameron only recently discovered American Hellenism, the worship of the 12 ancient Greek gods. “Because I work in the performing arts, I’m closest with Dionysus because he’s the god of the theater,” said Cameron.