As a 3D artist, Chris Hayward fulfilled a childhood dream that took fruit when he saw dinosaurs come to life on screen in the 1993 movie, “Jurassic Park.”

In college, the 32-year-old learned how to animate and create 3D worlds like what you see in movies and in video games. But working in the industry proved an adult nightmare, as Hayward was laid off three times in six years, due to the precarious nature of his profession.

Digital artists are often hired at the start of a project and fired at the end of its development cycle. They also compete with cheaper labor overseas as companies outsource work to cut down on labor costs.

“Every year, you're almost scared. When am I going to get laid off?” Hayward said, recalling a fear he no longer lives with, now that he’s set up his own studio at home in San Diego.

Going into business for himself has been made possible by powerful software, once expensive and out of reach to the average person. Now it’s free, spurring a boom in entrepreneurship in interactive media.

“I feel like, as artists, we are taking our power back,” Hayward said.

The technology at the core of his work is called a game engine, software used to build 3D worlds in which you can interact as a player, like what you see in video games and increasingly nowadays, in virtual reality.

The biggest engine makers have released powerful professional-level versions of their software for free, allowing the artists who use them more economic leverage, now that they can make products without being on a company’s payroll.

Game designer Erin Reynolds recalls the early days of her career. “As an individual, you couldn't — unless you're really rich or won the lottery or something like that — you couldn't purchase those tools by yourself.”

When the Unity Engine began giving out its full-featured product without too steep a learning curve, more artists like Reynolds began realizing their entrepreneurial ambitions and passion projects.

In late 2013, Reynolds founded her own studio, Flying Mollusk. Her team built their flagship game, “Never Mind,” using the Unity Engine. The effort was funded with a Kickstarter campaign that raised a little over $75,000. Flying Mollusk distributes its products via online marketplaces for games like Steam and Humble Bundle.

The Unity Engine began gobbling up market share as it offered interactive media professionals a more autonomous path to professional success.

“After Unity started attracting large numbers of veterans in the industry of all areas of expertise (artists, designers, programmers) that had struck out on their own after being laid off from big publishers, other engine makers were pretty much forced to follow suit,” said Marcos Sanchez, Unity’s head of global communications.

Unreal Engine went free in March of last year. Amazon released a free game engine this February, called Lumberyard. CryEngine jumped on the bandwagon one month later.

The business logic for the engine makers is that eventually, people will build products that generate revenue. Then they may owe royalties or have to purchase a pro version that includes some additional features.

Many students who learn on the free versions of game engines will go on to work for large studios, compelling major players to use the same software if that’s what their workforce is familiar with.

The Next Frontier

Game engines are currently powering exciting possibilities in the world of interactive media. Artists are using them to develop applications for virtual reality in an effort to solve problems in new ways.

The rewards could be great. Investors have poured $8.83 billion into virtual reality endeavors since 2012, according to market research firm SuperData.

Bryan Jaycox, a game design professor at Woodbury University in Burbank, California, says that many of his friends previously working in gaming have transitioned to startups in virtual reality.

Hayward and a business partner Harrison Schaen get lost in virtual reality at their home-based studio in San Diego.

Hayward and a business partner Harrison Schaen get lost in virtual reality at their home-based studio in San Diego.

“If you can be one of the first to the game, making your name in virtual reality, as a virtual reality experience designer, you’re going to do very well in this world,” Jaycox said.

That’s what Hayward is trying to do. An application he’s working on would allow users to interior decorate their home in VR instead of having to guess how a piece of furniture might look before purchasing it. He’s also conceptualizing a couple of virtual reality games.

“We have a huge opportunity now to be a leader in this new VR stuff because everyone is learning,” Hayward said.

Meanwhile, he’s been rejecting recruiters approaching him about out-of-state jobs. Instead, Hayward is working out of a home studio in San Diego along with a group of men and women — mostly digital media professionals all working on their own entrepreneurial endeavors.

They employ each other’s skills on projects for clients, acting as a sort of alternative studio — working independently, and yet together.

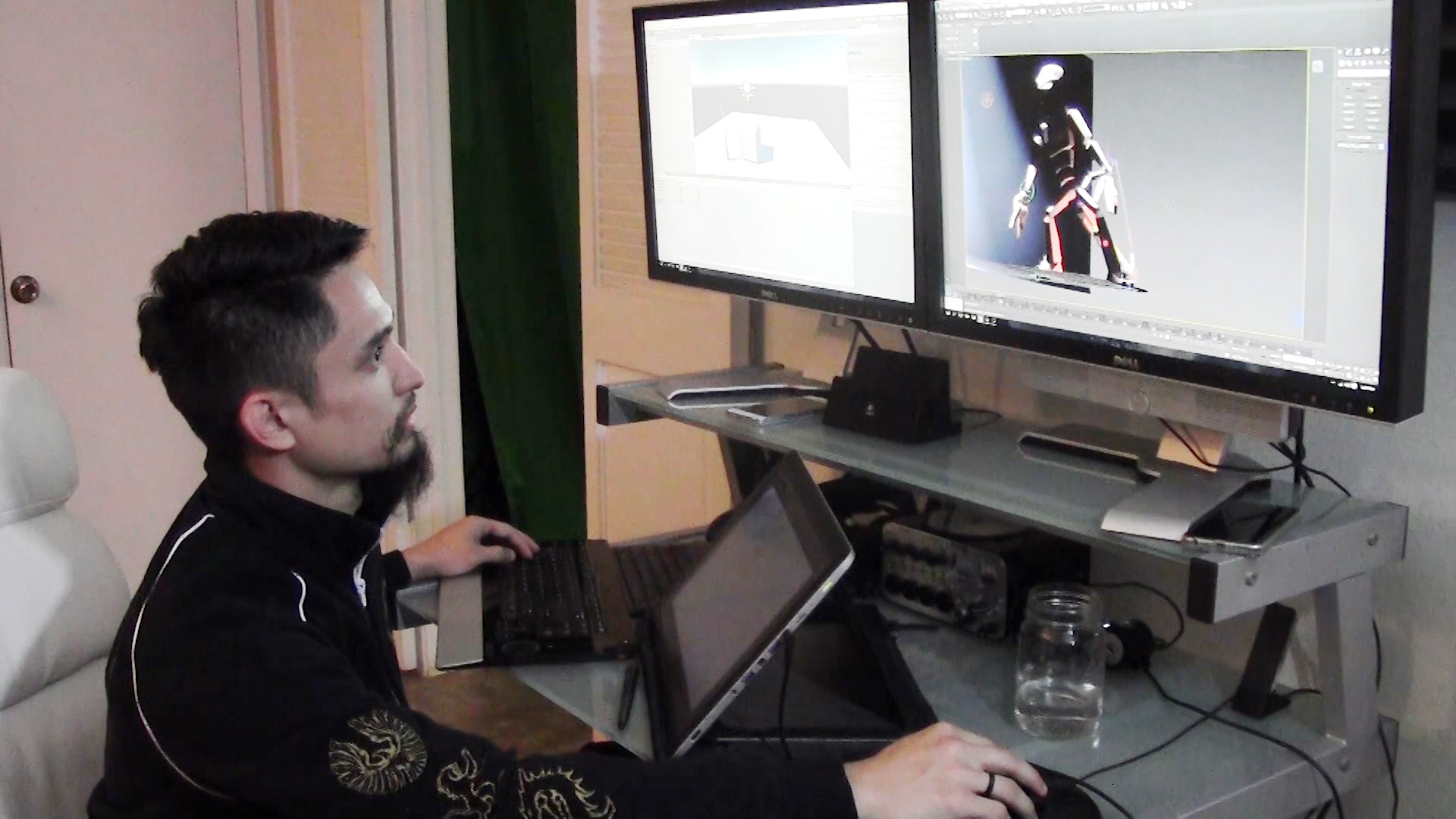

Hayward works out of a home-based studio in San Diego, along with a team of entrepreneurs and independent contractors.“I would rather be like the Minecraft guy who worked on his own passion thing and was able to profit off of that,” Hayward said, certain that he will get laid off again if he becomes employed at another company.

He’s referring to video game programmer Markus Persson, the ultimate indie success story. Persson became a billionaire off sales of the game he single-handedly developed, Minecraft.

But Persson is an anomaly. Bill Graner’s experience as an independent game designer speaks more to the masses who have ditched the corporate world and are creating products in small teams without the financial backing of a publisher.

“First we wanted to make games and sell them and make a living, which it turns out is not sustainable,” Graner said. For the last five years, he and his Crater House studio team, based out of a coworking space in San Francisco, have gotten by doing contract work for various clients.

However, they were recently paid a lump sum that will allow them to focus on their individual passion projects for the next nine months, “like an artist collective where we're each doing our own thing and helping each other out,” Graner said.

Figuring out how to making a living off your art is the ultimate question, says Los Angeles based indie game designer Nick Crockette. The 23-year-old takes on freelance gigs, working for six weeks here or there to support the time he devotes to his passion projects.

Crockette says he doesn’t plan to make a lot of money off his experimental games. But he gets to be an artist and express himself. “I could bring all this insane technical power to bear on something very small and maybe doesn’t even appeal to that many people, but it’s a thing I wanted to make,” he said.

How have some artists adapted to a volatile job market?

Tom Sito

Chair of the Animation and Digital Arts Division at the University of Southern California

Tom Sito eventually left the industry and joined academia. Sito says companies are maximizing profits by hiring temporary workers and outsourcing. "You want the latest technology, so you can't save any money on that," he said. "And you don’t want to save money on your own salary. So whose left? The employees."

But things haven’t changed all that much, Sito says. "It was like artists in the Renaissance. You get hired by the pope to decorate a wall. You're not employed year-round. It's until you finish the ceiling and you leave."

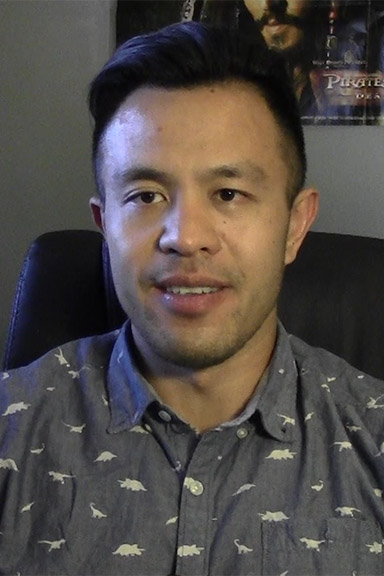

Andrew Souvannarath

3D Artist

“I’m always afraid of getting laid off, but that’s why I got to stay on top of my game. For example, I know more than just 3D. I could edit videos, retouch photos, do coffee runs, mop the floor. Just have other useful skills to back yourself up.”

Souvannarath was warned about the shaky job market for his profession while studying media arts and animation in college. It didn’t hit him however, until he was laid off for the first time, along with 70 percent of the staff at Legend 3D, whom had just wrapped up work on the films "Transformers," "Men in Black," and "The Smurfs." Souvannarath was also laid off at two more companies once projects wrapped up.

“It’s an emotional rollercoaster ride. You just have to start over and accept that this is going to be your life if you stay on this career path," he said. "If not, choose something else. Costco — they’ll take care of you. Or the military. If you start over from the bottom, at least in the end after a certain amount of hours or years you work there, they’ll take care of you. That’s not what I want. I don’t want to be an ant. I want to be an individual and spread my vision and creativity onto other people for them to enjoy and experience.”

Chris Hayward

3D Artist

Chris Hayward has set up his own home-based studio. He’s taking on freelance projects and developing his own products, using free game engines.

“In this day and age, I can take on different clients," he said. "I could work for people in the medical industry who need visualizations for a needle getting injected into an arm. I could do stuff for architecture. I could do stuff for advertising, motion design, graphic design. That’s helped me survive — as a jack of all trades, as opposed to being a specialist.”

Read more about Hayward's professional journey.

Travis Ripley

Digital Fabrication Specialist

Travis Ripley got an $80,000 degree in game design and development. The work wasn’t 100% fulfilling, and he eventually left the industry to work in manufacturing and make things with his hands. He says he's glad he got out.

“With my friends who are in gaming right now, a lot of times I see them where they’re like, ‘I don’t know. I just got laid off from my six-month job. I got to do something else again. I got to go out and pimp up my resume and pimp up my portfolio to go work at a game studio that will maybe only be around for two years.’ I got tired of that,” he said.

“I’m not really flushing [the degree] down the toilet — it helped me. But I was like, I’ve got to do something bigger and more grandiose.”