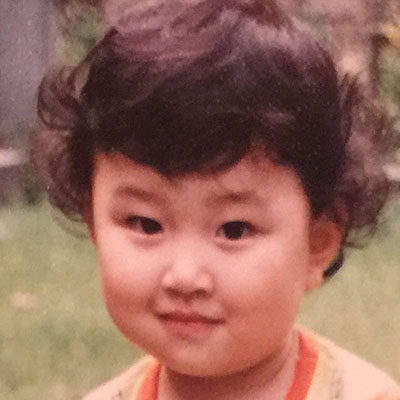

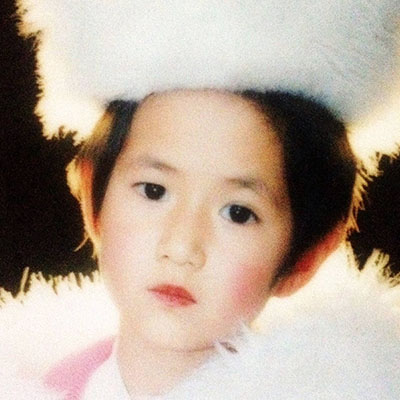

A Chinese TV show called "Super Brain" held a contest in 2017 between a human and a robot to test their abilities in facial recognition. The human representative, a memory expert named Feng Wang, and a robot called Xiao Du, built by Chinese search engine company Baidu, observed the childhood pictures of two girls and were then asked to find them in a group of performers who were dancing and singing onstage.

In this game, the human lost. Wang failed to recognize one of the girls, while the robot recognized both of them, and it identified a pair of twins, despite the difficulties caused by the movement of the performers. But do cases like this mean that the human brain is inferior to a computer?

Neuroscientist Irving Biederman, a professor of psychology and computer science at USC, is an expert on humans' ability to recognize and interpret what they see.

"Computers do it in a very different way than people might be doing it," he said. People have trouble recognizing many faces, he said, "because we have limited memory."

However, computers are not as good as humans in their perception and action, Biederman said. "Artificial neural networks have been modeled of biological neural networks, but we don't have models of the whole brain because there's a lot more complexity."

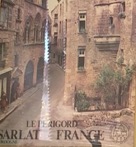

"You could make sense of it, right?" he said of the first image. "It actually is a mechanical brain." Of the second image, he said, "even though you never saw it before, in a fraction of a second you realize that it's a medieval town. But your computer can't tell until it's trained to see particular scenes like that."

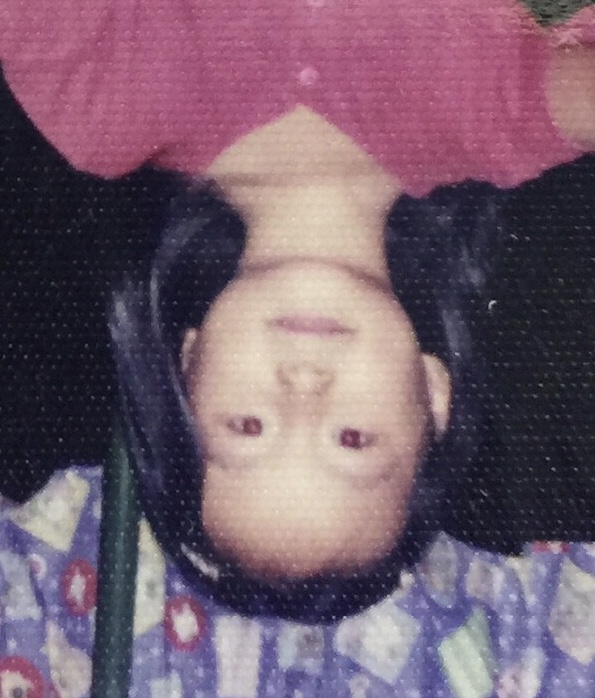

Saty Raghavachary, a senior lecturer in the Computer Science Department at USC who teaches graphics and animation courses, seconded Biederman's perspective. He said that in the case of the Chinese TV show "Super Brain," the robot seemed to surpass the human in facial recognition. However, a computer can't recognize a face in a photo if you change it — if you paint on the picture, or flip it or change the color to black and white — until it was trained, Raghavachary said. "But humans have no problem recognizing it."

Here are some of the examples when the computer can't recognize the faces:

He said that it's also the reason why Google's self-driving car is not mature enough yet to have widespread application. "There are too many exceptions," Raghavachary said. If you painted the stop sign blue or changed a letter or flipped it, the self-driving car couldn't recognize it. Or if there were a person standing in the middle of the highway with a big sign covering his or her face, the self-driving car would just drive through because it didn't see the person's face and thus recognize it as being a human, Raghavachary said.

As these researchers explain, the human brain and computers have their own areas of expertise, so we can't simply say that one of them is better or worse than the other.

The challenge, Biederman said, is to get the computer to learn with as little training as people need. Humans are good at perception. For example, he said, you just need to give them one or two instances of how a giraffe would look. People get the idea of its shape, and they'll be able to recognize it in different orientations. However, a computer needs to see the giraffe from all different shapes and angles before it can recognize it, Biederman said.

On the other hand, the computer will always have advantages in terms of working with data, databases, algorithms and modeling, thanks to their central processing units, graphics processing units, encoders, decoders and so forth.

"Right now, we're in a complementary association with computers," Biederman said. "For example, a computer can look at thousands of cases and then be able to say for this particular disease, if you get these symptoms, this bloodwork and this appearance, then it's a 97 percent chance that the person has this disease."

Biederman said that what we can do is benefit from computers and what they discover, and then use it in our own decision-making.

Match Game

Drag each adult photo into the empty box under its matching childhood picture.