Tika Thornton was only 12 years old when she first got trafficked.

One night while Thornton was roaming around the streets of South Central Los Angeles, a car pulled up along the side of her. Inside the car was a young man in his 20s who looked nice.

"He asked me if I was OK," Thornton said, "I told him I was fine, and I started to walk away and it started to rain.

"He was like, well just come sit in the car with me until the rain stops," Thornton said.

It was cold and wet, as it had been raining throughout the day, so she agreed and got in the car.

Once Thornton got into the stranger's car, the young man started asking Thornton questions. He seemed nice and sweet, according to Thornton, and after a while, she was feeling more comfortable

He then pulled out a joint and asked if she wanted to smoke some weed. Although Thornton had never smoked before, she was used to seeing people smoking weed. So she thought, 'Well, what's the harm in it?'

Thornton paused and was silent. After a minute or two, she continued: "So I kind of, like, blacked-out … because, apparently, he laced the weed."

Thornton said that when she woke up in a fuzzy state, she was no longer in the man's car. Instead, she was in an unfamiliar room, tied up to the bed. "I felt pain and there was moisture dripping on my face," she said. "I tried to move my hands, but I couldn't."

When Thornton regained her consciousness and strength, she looked around. She was tied to the bed, on top of a dirty mattress with no sheets. "Guys were just coming in and out," she recalled, "I was basically getting raped over and over again by a bunch of different guys."

From then on, Thornton began a new 'life,' in which she was raped, beaten and sold, day after day.

"From that moment on, I just stayed in the streets," Thornton said. "I couldn't imagine myself getting out of that situation. I felt worthless. I had little to no self-esteem."

A deep pull of discomfort and sorrow welled up in her gut. Thornton recalled how she would work all day, often into the early hours of the morning.

"I would see kids my age going to school, and it was hard for me to look at those kids because there was a lot of shame."

Thornton's’ life was never easy, even before she met her pimp.

Thornton grew up in South Los Angeles. Her mother used drugs and abused her, while her father was absent.

"My home life was very violent because of the things that I'd been through in my life being sexually molested at a young age having," Thornton said. From the age of 6 to 9, she was repeatedly molested by one of her uncles. She kept quiet and didn't tell anyone about the sexual abuse until she was 12 years old. The first person she confided in was her mother, who then called Thornton's grandmother.

"My mom called my grandmother and told her what I said," Thornton recalled, "and my grandmother didn't believe."

"So my mom didn't do anything after -- she didn't call the police, so nothing happened," Thornton explained. "And at that moment, I felt like, you know, nobody gives a shit about me."

Thornton now spends her days mentoring girls who’ve been arrested, providing peer counseling to survivors of sex trafficking and educating the public about modern forms of slavery. She says that victims are often left with trauma, addiction and lengthy criminal records.

Race Connection

The plight of Thornton is shockingly common. Most sexually trafficked juveniles are girls, and like Thornton, are from the margins of society.

While data on the prevalence of human trafficking in the United States are scarce, some research suggests that trafficking is widespread. Hence, it's unclear whether any of these numbers are an accurate representation of the problem because many cases simply aren’t reported, according to Thornton, who now works as a crisis response case manager for Journey Out, a nonprofit organization that partners with the Los Angeles Regional Human Trafficking Task Force.

Any vulnerable minor can be a victim of sex trafficking, but how these numbers are reported is often overlooked. Also, the demography of domestic sex trafficking victims in the United States is seldom discussed.

In 2013, the Office of Victims of Crime reported that 40.4 percent of the confirmed victims of human trafficking were African-American. According to a recent report by Rights4Girls, an advocacy organization working to improve the lives of marginalized women, "not only are women of color disproportionately impacted by human trafficking, but they are also the majority of individuals criminalized for their exploitation."

Multiple studies suggest that children of color make up a disproportionate number of sexually exploited children in the United States. For example, a study conducted by The Black & Missing Foundation foundation reported in 2015 "that of the 635,155 children of all races who went missing in America in 2014, 36.8 percent of children ages 17and under were African-American."

Two studies conducted in New York reported similar trends. One study found that half of all street-walking prostituted minors in New York City consisted of African American minors, while 25 percent consisted of Latino. A separate study found that up to 67 percent of under-age prostitutes in New York were African-American and another 20 percent were Latino.

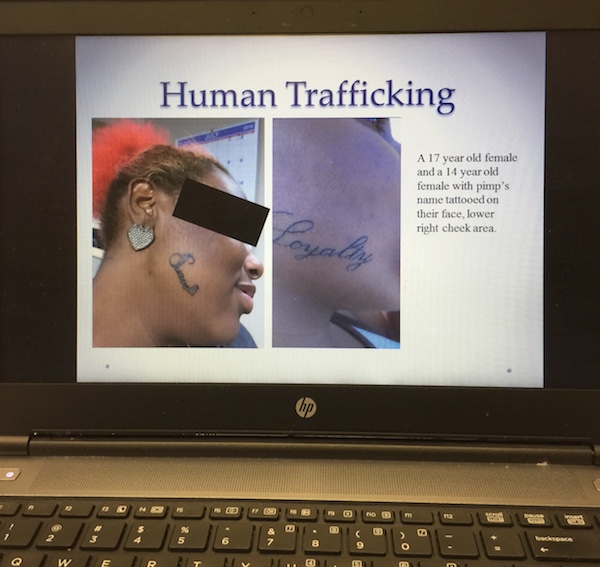

This pattern of disproportionality also exists in California. For example, in Alameda County, 66 percent of all youth referred to a human rights organization exclusively serving commercially sexually exploited children (CSEC) were African American. Citing the data provided by the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the organization found that "in Los Angeles County, 92 percent of girls in the juvenile justice system identified as trafficking victims were African-American." Of those children, 62 percent were from the child-welfare system and 84 percent came from low-income neighborhoods in the southeastern part of L.A. County.

In a 2015 review, titled "The Racial Roots of Human Trafficking," Cheryl Nelson Butler, an assistant professor of law at Southern Methodist University, wrote that "domestic sex trafficking of minors is not only prevalent, but a strong nexus also exists between sex trafficking and race." Moreover, according to the National Center for Victims of Crimes, "compared with other segments of the population, victimization rates for African-American children and youths are even higher."

Statistics show that these racial profiles mirror a national epidemic.

African American & Latino youth are overrepresented in child sex trafficking cases.

52% of all juvenile prostitution arrests are African-American children. [Source: FBI UCR]

“Black girls are disproportionately prosecuted for prostitution offenses yet their narratives are seldom heard,” Jasmine Phillips, a law clerk for the Hon. Ronald L. Ellis of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York wrote during her tenure as a graduate student at the UCLA School of Law.

African American & Latino youth are overrepresented in child sex trafficking cases.

52% of all juvenile prostitution arrests are African-American children. [Source: FBI UCR]

“Black youth account for approximately 62 percent of minors arrested for prostitution offenses in the United States, even though blacks only make up 13.2 percent of the population,” Philips wrote, citing the FBI’S 2013 UCR report.

In 2016, an estimated 1 out of 6 endangered runaways reported to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children were likely child sex trafficking victims. 86% of these likely sex trafficking victims were in the care of social services or foster care when they went missing [Source:NCMEC].

Despite these trends, advocates* have argued that the role of race and racism in making children vulnerable to domestic child sex trafficking has not been fully addressed to date. Journalist Jamaal Bell wrote in a Huffington Post article that "a link that is rarely discussed in open forums about human trafficking is racial discrimination."

Bell concluded that the connection between race and sex trafficking is unclear, yet undeniable— "a link that is rarely discussed in open forums about human trafficking is racial discrimination."