A Familiar Resource During Transition Planning: Regional Centers

How regional centers can help families during the transition process

Parents, caregivers and others gathered at the Koch-Young Resource Center at the Frank D. Lanterman Regional Center. Upon arrival, everyone was given a folder full of papers about transitioning into adulthood. Attendees came to learn about what to expect during the transition process for the people in their lives who have developmental disabilities. Such sessions are among the many services that the regional center provides at its facilities in the Koreatown neighborhood west of downtown Los Angeles.

The transition process takes years to complete. In some cases, the process can start as early as middle school. However, the transition plan must be completed by age 16, according to the federal law called the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).

Map of California regional centers and the corresponding field offices.

Under IDEA, the transition plan is outlined in the Individualized Education Program (IEP), where the child, family, teachers and anyone else who is vital in providing services meet to discuss goals and objectives, auxiliary services, review the past year and revise the IEP as necessary. The IEP begins at the age when a child is deemed eligible for special education services in the school system.

In California, the specific section that details plans for adulthood is called the Individual Transition Plan (ITP). The ITP can include whether the child wants to go to college, have vocational training, live on their own and how they will participate in the community.

For some parents, the transition process can be a little overwhelming.

“There hasn’t been a step along the way where I don’t constantly worry about navigating and what we need to do to support [my daughter] in thriving as an adult when her dad and I are no longer here,” said Grenda David.

But one expert suggests parents can manage the next stage in their child’s life by starting with minor decisions.

“It can start with making choices about what you want to eat or what you want to wear. Those are not terribly threatening things,” said Fran Goldfarb, director of family support at USC University Center for Disabilities at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. “It starts by tolerating your child learning to do something as opposed to…requiring them to know how to do something.”

In California, regional centers can play a key role in matching parents and their children with the resources they need throughout this process. According to the Department of Developmental Services, regional centers are nonprofit private corporations that contract with it “to provide or coordinate services and supports for individuals with developmental disabilities.” California currently has 21 regional centers and over 40 offices placed by population and geography across the state. The centers are contracted through the Department of Developmental Services and served over 250,000 clients in 2015. More than 17 percent of those served were at the transition age.

Animated explainer video of the Lanterman Developmental Disabilities Services Act. If video doesn't play click here.

Regional centers were set up as a way to fulfill the criteria of the Lanterman Developmental Disabilities Services Act, a California law passed in 1969. The philosophy underlying the law is that “people with developmental disabilities and their families have a right to get the services and supports they need to live like people who don’t have disabilities.” Regional centers have to help people with developmental disabilities with the services they need and give information that will help parents and their child make informed decisions.

These services include counseling, outreach, training and educational opportunities for individuals and families, early intervention services for infants and their families, and lifelong individualized planning and service coordination.

Some programs, like the personalized community supports services at the Tierra del Sol Foundation, are funded through the regional centers, said Jacquie Williams, an intake coordinator at the nonprofit group. It provides one staff member for every person served.

“It’s very individualized,” she said. “In that situation, a staff [member] can go and work with someone and help someone to do whatever they want to accomplish in life. Whether that’s taking college classes and they need a person there with them. Looking for a job, it can be looking for an apartment, it can be learning their way around town, taking a class, going to paint night, meeting up with friends, going to bowling, go to the YMCA or volunteering.”

Tierra del Sol also provides independent living services, helping clients learn the skills they need to live independently, such as cooking, grocery shopping and washing clothes.

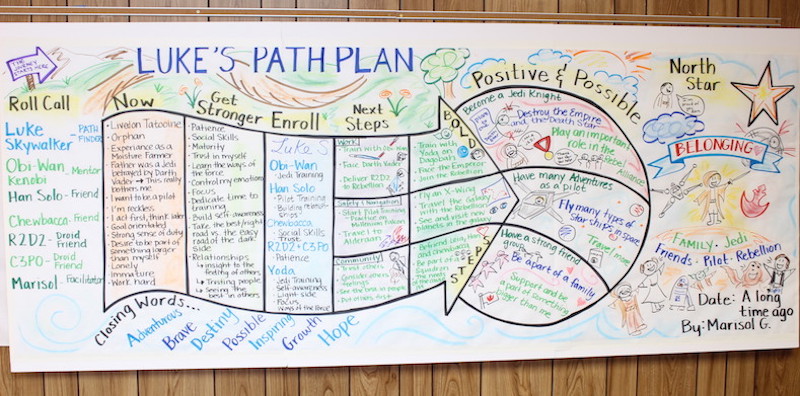

The Tierra del Sol Foundation in Sunland shows an example of a path plan for the "Star Wars" character Luke Skywalker.

Tierra del Sol’s programs are based on a path plan created for many clients in the transition age, which takes about two hours to complete. The path plan is essentially a layout of clients’ hopes and goals. Even before fully committing to participating with the organization, Williams says, parents should make sure their children have enough life experiences so that they can find something that they would really like to do.

“Families that have in mind who their son or daughter is, what makes them tick, what they want to do, what they like to do, that’s a huge thing right there,” she said. “Then just to start early looking at places. Looking at places in your home community that would be a good-fit program you know. Look early because it is a process.”

Another major part of the transition process is planning the living arrangements. If the child with developmental disabilities is not going to stay in the family home, there are many options to choose from. Among these are a community care facility, a developmental center, a family home agency or living on their own with independent or supported living services. Despite the range of choices, more than 76 percent of consumers served by the California Department of Developmental Services choose to stay in their family home.