Sweida's forests before the war

Some of the trees are estimated to be more than 2000 years old.

(Credit: Walid El-Atrache)

Some of the trees are estimated to be more than 2000 years old.

(Credit: Walid El-Atrache)

Those who cannot afford diesel for heating have resorted to cutting trees.

(Credit: Walid El-Atrache)

Sweida's city centre

before 2011.

(Credit: Walid El-Atrache)

Several refugee tents have been erected on the side of the road.

(Credit: Walid El-Atrache)

Due to the scarcity of fuel, drivers have to line up for hours at times to fill up their cars.

(Credit: Walid El-Atrache)

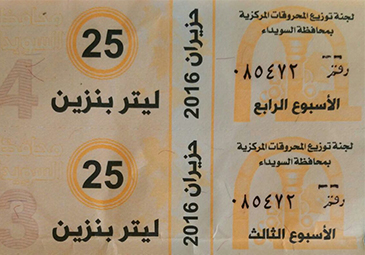

Fuel is now rationed in Sweida. Private cars get 25 liters per week, while taxis get 30 liters.

(Credit: Walid El-Atrache)

The costal city of Tartous

in April 2016.

(Credit: Iad Tawil)

The costal city of Latakia

in April 2016.

(Credit: Iad Tawil)

When Syria descended into war in 2011, I could not believe it. No one could. I remember strolling through old Damascus in the Bab Touma (or Thomas’ Gate) district on Jan. 6, 2011, the Greek Orthodox Christmas Eve. Some people attended Mass, while others celebrated and danced in the many restaurants and bars. The Hamadyeh Souq, the famous centuries-old market, appeared as vibrant as ever. Little did I know this would be the last time I would see Syria before the war.

The Sweida countryside in spring (Credit: Walid El-Atrache).

The Sweida countryside in spring (Credit: Walid El-Atrache).

I was born in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, where I spent half of my childhood. I then lived in Dubai, United Arab Emirates for more than 20 years, before moving to Los Angeles. I have never permanently resided in Syria, but visit on holidays. After living most of their adult lives abroad, my parents retired and moved back to their hometown of Sweida, in the south of Syria, in 2002. I see them several times a year. The war makes access challenging, even though Sweida remains mostly conflict-free.

The first time I returned to Syria after the war erupted was in early September 2011, six months after the first series of uprising had taken place. It struck me how things had changed. Military checkpoints seemed everywhere. The atmosphere felt grim. Businesses in Damascus and Sweida struggled. Some had closed, while others complained about operating at a loss. The robust summer nightlife was gone. People had to adjust to being home soon after sunset, because it was unsafe to venture outside after dark.

I never witnessed any fighting or violence in my few visits to Syria since the war broke out, but I heard many horror stories from people who had left rebel-held areas. A man who works for my father had to leave his hometown near the war-ravaged city of Aleppo, because it is now under ISIL control. He was telling me how a doctor was once operating on a patient alone in her clinic. She ran out of a medicine she needed for her patient, so she ran to the pharmacy across the street to buy some. But there was a problem. She forgot to cover her head before stepping out of her clinic. ISIL’s religious police quickly spotted her and sent a group of female fighters – all of whom were foreigners and spoke no Arabic – to her clinic. These women showed no mercy. They proceeded to kill the doctor in the most primitive of ways. As she was outnumbered, they bit her to death, like an animal would maul a human being. Another man, also from the province of Aleppo, who now lives in Sweida, told me that if he got caught smoking a cigarette in his hometown, ISIL fighters would mutilate his index and middle fingers, to discourage him and others from ever smoking again.

Other stories hit closer to home. There was a time from late 2012 to mid-2014 when I could not visit my parents anymore, because of the threat of terrorist snipers along the Damascus-Sweida highway. A relative on my father’s side was driving to Damascus with her husband in 2012, when she was shot in the hip by a sniper, hitting a major vein. It was just like a scene from the 2006 movie "Babel," about a woman who gets accidentally shot while on a bus tour with her husband in Morocco. As soon as she was shot, my relative’s husband rushed her to the nearest hospital when they arrived in Damascus. On his way, he had passed through several military checkpoints, where the army was informed about the incident. They intercepted the sniper, and shot him. The sniper was later identified as a foreign fighter from Libya. Meanwhile, my relative survived, but was temporarily paralyzed from the waist down. After a complicated surgery, she had to undergo a full year of physiotherapy before she was able to walk again. Another relative was once traveling to Damascus by bus in 2013, when he bent over to grab something from his backpack. It was during these few seconds that a bullet, also launched by a sniper, flew over his head, narrowly missing him. Had he not reached for his bag, he would probably not be here today.

While Sweida has remained relatively safe during the war, areas surrounding the province have not. To the west of Sweida, the army regularly clashes with Al Nusra Front fighters. To the east, ISIL poses a daily threat to the villages in the east of the Sweida province. Apart from 18 months during 2012-2014, the highway from Sweida to Damascus is mainly safe during the day. However at night, it can be dangerous. In fact, I traveled to Sweida in March for almost two weeks. I was told that the night before I arrived, a stretch of the highway had been closed because the army had intercepted ISIL fighters smuggling weapons from the east to Al Nusra Front fighters in the west. After the smugglers were caught, the highway reopened.

People in Damascus, Sweida, and other stable cities yearn for normalcy in their everyday lives. Since 2014, most of the fighting has been concentrated in the north of Syria. People have started going out again at night, making the conditions at night much safer than before. I was surprised during my last visit to see Sweida’s restaurants, cafes, and bars packed. It is as if everyone has become numb to living in a state of war. Ask them and they will tell you that life goes on and years pass by. Even wedding ceremonies, though they are now held on a smaller scale, continue to be celebrations where people sing, dance, and try to forget about the war for a while.

Teshrin Square in the city of Sweida (Credit: Walid El-Atrache).

Teshrin Square in the city of Sweida (Credit: Walid El-Atrache).

I cannot help but think about the generation of children growing up in this war, many of whom have had to miss school for months, if not years on end. Education in Syria is free, so those who stayed in Syria have been better off than many of the refugees who fled to Jordan, Lebanon, or Turkey. In Syria, education for all Syrians remains the government’s responsibility, and most children are still going to school, including those who have been internally displaced by the war. But in foreign countries, many children have had to miss out on their education. It will be important to focus on them and help them find jobs once they come of age. The reconstruction of Syria will be important, but ensuring the new generation adapts to a normal, daily life after the war is of the utmost priority. All Syrians have a duty to help the youth get back on track.