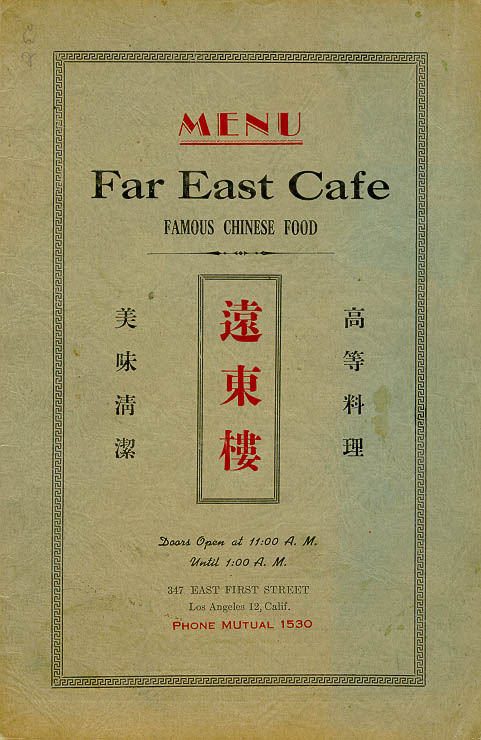

Far East Cafe

1930s

A history of Chinese immigrants who brought the food and culture to Los Angeles.

By Coco Liu

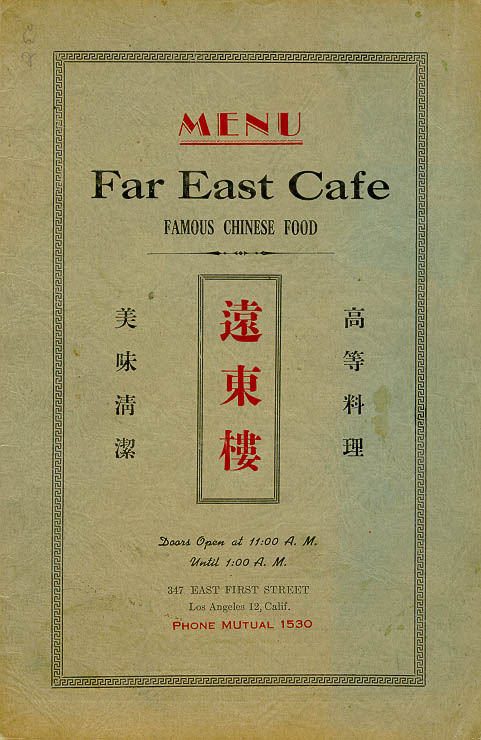

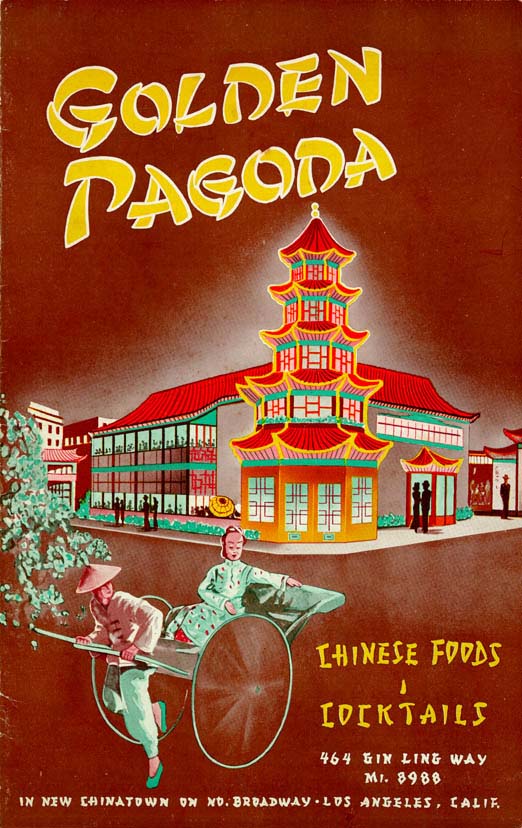

1930s

1930s

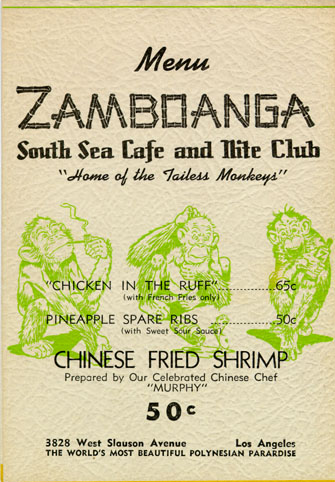

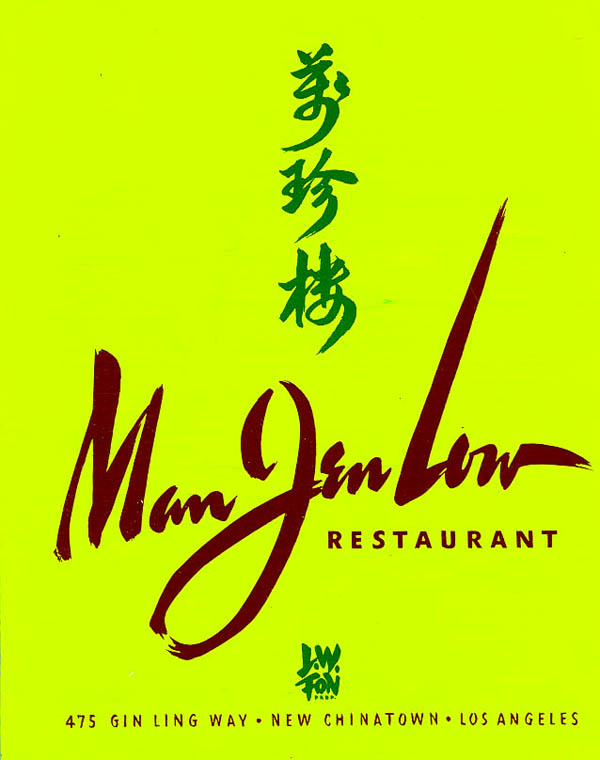

1940s

1943

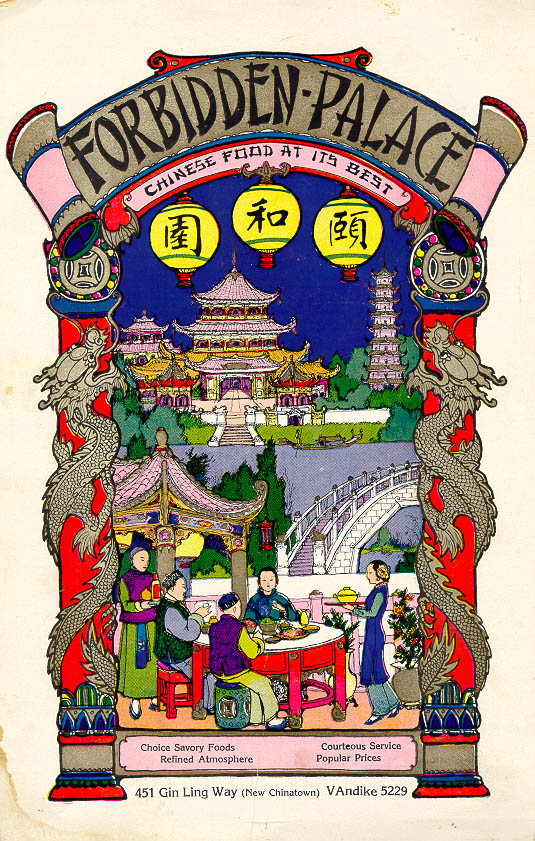

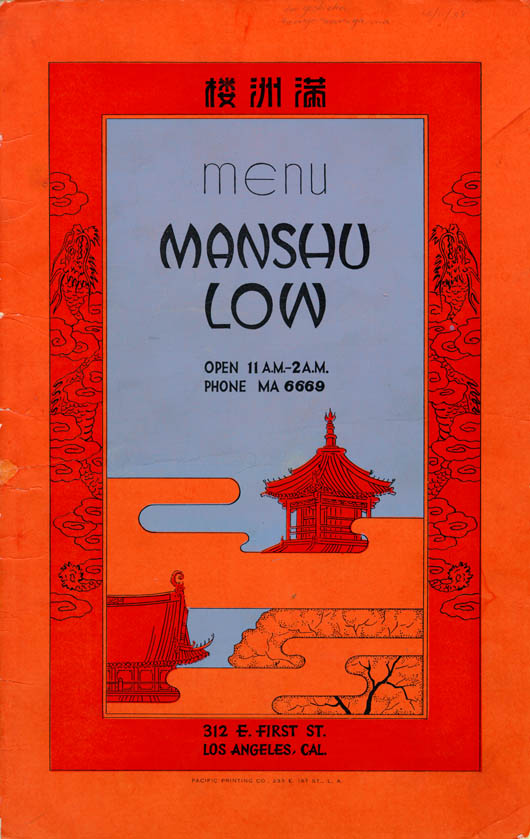

1950s

1950s

1950s

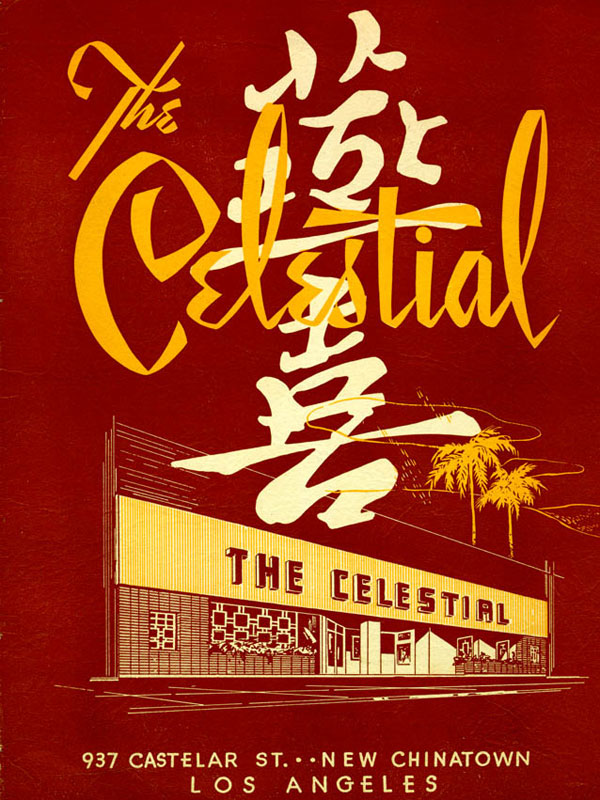

1960s

1964

1970s

2009

A set of Tianjin Pancake. Credit/ Mengchen Liu

A set of Tianjin Pancake. Credit/ Mengchen Liu

Quanhai Jin sat me down at one of his restaurant’s tables. He wouldn’t charge me for the brunch I ordered, which is a very Chinese thing to do.

“It’s free just for this time,” said Jin, adding, “look at you, too young to be away from home.”

Resistance would be rude. So we sat down face to face, with a very authentic northern Chinese breakfast between us — a bowl of tofu soup with various dressings and a huge Tianjin pancake, extra hot.

Fortune No. 1 is located in the San Gabriel Valley, just 15-minutes east of downtown Los Angeles, without traffic, of course. I looked out of the window of Jin’s restaurant. All the signs on the street were in Chinese. For a brief moment, I thought I was home.

Jin has been in Los Angeles for more than a decade. He is one of the early mainland migrants who came to the United States. But immigrants from China have had a long and not always happy history in Los Angeles.

The first wave of Chinese immigrants arrived during the Gold Rush in the 1850s. They built the foundation of Chinatown and brought working-class Chinese food to LA.

After immigration law removed unfair restrictions on the number of Chinese in 1965, the second wave of Chinese were upper-class immigrants from Taiwan and Hong Kong. They brought chefs who didn’t cater to their white client’s tastes. Instead, they promoted authentic Chinese flavors.

The third wave of immigrants brought diversity from all regions of Mainland China, and has enriched the variety and quality of Chinese food in LA. Jin is one of them. Today, the San Gabriel Valley is one of the most preferred destinations of Chinese immigrants in Los Angeles.

A history of Chinese immigrants in the states.Jin is one of 660,000 Chinese Americans in Los Angeles County. Being an ocean away from his hometown, Tianjin, was not his intention.

“I was in Mexico attending a convention,” Jin said, “next thing I knew, I was already in the U.S.”

“Wait, you didn’t plan to come to America?”

“I’m going to tell you what I told the court: I didn’t realize it when I crossed the border. How was I supposed to know that this side of a mountain was Mexico and the other side was the U.S.?” he said.

“And they believed you?”

“It’s the truth,” said Jin, who was not offended by what I had implied. He’s been in the U.S. for 13 years, and has never gone back to China.

Behind us, Jin’s wife and sisters-in-law were making steamed stuffed buns. The family came four years ago to help Jin open the restaurant. Before becoming an owner, Jin spent eight years doing “this and that” and one year working at a Chinese restaurant.

“So they just let you stay?” I was amazed by Jin’s story.

“I said that I didn’t care if they were to ship me back to China.They then asked where I prefer to be, the U.S. or China. So I answered ‘If you put it that way, it is better here, sir.’ And they offered me a job. One year later, I got my green card,” said Jin.

I couldn’t tell if Jin was exaggerating about how he got his citizenship. After all, he’s from Tianjin, a port city right next to Beijing, famous for the comic talent of its people. One thing he said was definitely true, Fortune No.1 offers decent northern Chinese cuisines.

“I’ve been coming here since the opening,” said customer James Shi, a former cook who came from Northeast China. “By the time I came, there weren’t a lot mainlanders, especially northern mainlanders in the U.S. If I wanted soy milk and fried dough, I had to go to the Taiwanese breakfast chain, Yonghe Soy milk. The food there is sweet and plain, which suits the southern people, not us.”

Chinese food in Los Angeles wasn’t as diverse and cheap as today’s before mainlanders from different regions brought various flavors and competitive qualities here. Customers who used to put up with some-what similar food as substitute now found their oasis. David Chan, the man who has eaten at more than 6500 restaurants in the U.S. told me that it’s getting harder and harder for him to keep up his spread sheet of comments on restaurants with the blossoms of Chinese restaurants, especially in the past five years. San Gabriel Valley along has, according to Chan’s estimate, approximately 600 to 800 Chinese restaurants, 200 on Valley Boulevard alone.

“There are outstanding Sichuan, Shanghai, Beijing, Dongbei, Taiwanese, and other regional Chinese-style restaurants to be found in California,” David Chan said, “the Chinese cuisine in Los Angeles is more mixed to fit the taste of a more diverse and sophisticated clientele.”

Competition pressed the price down. For five, six bucks, you can have a set of tofu soup and eight steamed stuff buns. Even better, you normally don’t need to tip in a Chinese restaurant. (Nobody can figure out the broken tipping system anyway! Give it up!)

The popularity of Fortune No.1 can be exciting and tiring for Jin. Even with the whole family here to help, Jin still works almost 16 hours a day. He starts making dough and fillings for the steamed buns from 3 a.m. and finishes cleaning up at 11p.m. He works seven days a week with 2-hour naps at lunch.

“Of course it’s tiring,” Jin said, “ but everyday these good fellows line up to get breakfast and start a day, I can’t bear to let any one of them down.”

This dedication and hard-work reminds me of Mrs. Chan. She recently became the owner of a West Hollywood restaurant called Hunan Tasty, where she and her husband has been working at as waitress and cook for 30 years.

Chan is from Toishan, China. I’ve never heard of this city, but apparently, it’s famous for sending immigrants to the U.S.

David Chan, who is no relative to the Mrs. Chan, told me that most of the Chinese who came before 1965 were from this particularly rural area by the Guangdong Province called Toishan.

“The Toishanese came to America because of a combination of dire circumstances at home and easy access to the seaport of Canton,” David Chan said, “…as the only nationality barred from coming to the United States, the Chinese resorted to various forms of illegal entry to come here anyway. But those who came surreptitiously were exclusively relatives or neighbors of Chinese already here, keeping the population homogeneously Toishanese.”

It took quite a while before I get to know about Mrs. Chan. Even at the end of the interview, Chan wouldn’t give her first or maiden name. She is a shy, slow speaker, not wordy at all. At first, with each question I asked, she’d hesitate for a bit and give me very short answers.

“What did you do back in China?” I asked.

“Peasant.”

“What’s hard for you when you first came?”

“Language,” she said.

“Why did you come?”

“It’s better here.”

The question that broke the ice was “what’s your most unforgettable experience.” I thought she’d talk more about preparing for the citizenship test, the isolation of Chinese immigrants back in those days, or their poor living conditions when they first came.

But she thought about it for a while and started talking about her two sons. “I’m really glad that both of my sons went to college,” she said.

I asked where they went to school and what they studied.

“I don’t know anything about their major,” the mom hesitated again and answered with a self-mocking laughter, “I can’t understand them.”

Her sons used to speak Toishanese before elementary school. Like many second generation Chinese-Americans, they forgot their mother tongue once they fit into U.S. society. Meanwhile, the parents spoke broken English with a thick Chinese accent.

The mutual frustration caused by communication melt-downs drove the parents and kids apart. Chan told me that if the sons have anything important to tell her about, they’d get a relative on the phone and translate for them.

“So do you ever feel lonely?” I asked.

“We don’t think about that… It was hard. By the time we came, we had nothing to brought with us. I just bought an air ticket and came. We never had time to think about this kind of things,”

The couple, like Jin from Fortune No.1, still works more than 14 to 15 hours a day. Nothing has changed since they bought the restaurant that they’ve been working at for over two decades, except for the name: they changed “Hunan Taste” to “Hunan Tasty.”

“We don’t change. The old customers recognize my husband’s cooking. You know the foreigners, if you change, they don’t come any more.”

Clarissa Wei, the 24-year-old foodie who used to work with food critic Jonathan Gold, said that Chinese restaurants are relatively more conservative when it comes to changes. For the first-wave Chinese migrants, changes are considered dangerous.

Lack of motives is another factor. The first-generation, deep-rooted Americanized, merchandised “Chinese” flavor has been the most widely accepted one. Although Chop Soey and Stir-Fries are not using Chinese recipes, but rather are rough, working-class dishes that came out of very limited ingredients, they are still well-known and defining many’s impressions of Chinese food. That’s why until this day, restaurant owners like Chan and her husband chose to stay the way they always have been.

Another woman in the food industry, Eliana Zhang, is the owner of one of the 15 Phoenix Food Boutique branches in Los Angeles. She’s been working in the 50-year-old family run business since the 1990s.

Zhang showed up at Phoenix Food Boutique wearing a cashmere turtleneck and a silk scarf, with a young assistant in a suit standing behind her. I waited for her for almost an hour in their dessert store next door to the restaurant.

The minute she started talking, I knew she was worth the wait. She came from Hong Kong and went to USC. Zhang is a perfect representative of the well-educated, upper-class, second wave immigrants from Hong Kong or Taiwan.

“I’m here to support the kids,” that’s the first thing Zhang said to me, “I went to USC myself.”

Zhang showed great interest in me and she’s good at chatting. She asked about my master’s program, my life plan, and my ice cream preference. That’s where I realized that Zhang had been dominating the interview without me noticing it.

It’s interesting how Zhang’s character of taking control reflects in her philosophy of running the restaurant. She’s one of the second-wave immigrants, who brought well-trained chef who won’t cater to the western preference. A gradually obvious feature of Chinese food in Los Angeles and the U.S. after 1965 is authenticity, which brought up the rates of Chinese restaurants. A lot of restaurants that opened in the 70s and still standing today are high-end Cantonese or Taiwanese restaurants. The second-wave Chinese immigrants changed the stereotype towards Chinese food and “cultivated” the western customers to get used to the real Cantonese and Taiwanese flavor by emphasizing quality and taking innovations. That’s exactly what Zhang did with her desserts.

Hong Kong Egg Waffle. Credit/ Instagram user xmascarol

Hong Kong Egg Waffle. Credit/ Instagram user xmascarol

“I studied in Le Cordon Bleu in France,” Zhang said, “by the time I went back to Los Angeles, no Chinese restaurant was offering decent desserts after meals. That’s like a sentence without a period to me. It bothered me.”

At the time, dessert at a Chinese restaurant was normally a bowl of black sesame soup or sweet rice dumplings served for free. Zhang believes that she’s the first one to charge people because she’s confident with the quality of their deserts.

“They questioned me for taking that move,” Zhang said, “they thought it would affect the business. Oh boy, were they wrong.”

The training at Le Cordon Bleu made Zhang very strict about dessert. Everything was made from scratch. The sesame was ground everyday, the dumplings were hand-made.

“You don’t have to know anything about Chinese culture to tell the differences between hot water with old machine-ground sesame paste and slowly boiled, fresh hand-ground sesame paste.” Zhang said.

Her dessert sold out every night. By 1999, Zhang opened the first Phoenix Food Dessert of the current 15 branches. She saw to it that their dessert never stop evolving by introducing desert from different continents to the menu, using French or Italian recipes and Chinese ingredients to make new desserts and sticking with daily made, start-from-scratch products. For their rice puddings, for example, the Phoenix Food Dessert is using an Italian recipe called Pana Cotta, but switching the ingredients to red-bean, matcha or coconut milk.

“Dessert is about joy, about ending a meal with satisfaction,” Zhang said, “It’s essential and I want to make sure that people are aware of the fact.”