Steve Sax

Former second baseman Steve Sax was a five-time all-star and a two-time World Series champion who played 14 seasons in the Major Leagues. He is, if unfortunately, best remembered for a strange hiccup early in his years with Los Angeles Dodgers: he would over-throw the catcher or first baseman after fielding a routine ground ball.

Sax was haunted by a mental block, known primarily in the golf world as the “yips.”

Thought by many to be a mythological plague, the yips is instead a very real mental hurdle. It can stop the best athletes from performing routine tasks like sinking a two-foot putt or throwing it to first base after fielding a ground ball.

Though most commonly associated with golf, the yips have also plagued athletes in a variety of other sports: tennis, track and field, swimming and diving, archery, shooting, darts, table tennis and baseball.

Sax had his best years in Los Angeles, where his consistent bat and solid fielding helped lead the Dodgers to World Series victories in 1981 and in 1988. After that 1988 championship, he moved on to the New York Yankees and then to the Chicago White Sox and Oakland A’s.

In 1982, Sax was the National League rookie of the year.

In 1983 – the yips.

Dr. Richard Crowley, a sports psychologist who worked with Sax during that 1983 season, said the yips can affect “all athletes regardless of the sport.”

Crowley said, “All of our fears and anxieties are kept in a part of our brains called the ‘unconscious’ and, generally, what happens with the yips is that something external happens that stirs up those emotions in the unconscious, and all of a sudden the most confident player who is doing really great can’t seem to throw the ball anymore and can’t pinpoint why that is.”

For Sax, the moment that stirred his unconscious came in the ninth inning of the Dodgers’ 1983 home opener against the Montreal Expos.

Expos outfielder Andre Dawson tripled into right field. Sax ran out into shallow right to take the cut-off throw. Dawson stopped at third base. Sax rifled a throw home, anyway. The ball bounced in the dirt and got past the catcher, allowing Dawson to score easily.

“It was a pretty average error for him,” recalled Crowley of the play, “but he started thinking about it and started losing his confidence.”

By mid-August, Sax had recorded 30 errors. Almost all of them were on stray throws that occurred after routine groundballs.

During the 1983 All-Star Game, Sax demonstrated his throwing yips in front of a national audience, bouncing a throw over to first baseman Al Oliver less than 40 feet away. Following his performance, routine throwing errors became known as “Sax Attacks,” or “Steve Sax Disease.”

"That was the most mysterious part about Steve’s yips,” said former Dodgers general manager Fred Claire. “They only seemed to happen on easier plays.

“He’d be fine firing a tough throw from deep behind second base. But on the easy dribblers is when he would think and freeze up.”

The split-second of time between fielding a slow roller and tossing the ball to first base was enough time for Sax to start thinking. And, according to Dr. Crowley, that’s exactly what his problem was.

“An athlete can not worry about failing,” Crowley said. “Once the fear of failure enters an athlete’s unconscious mind, that’s when the yips occur.”

“If Steve laid out to stop a grounder up the middle and quickly got up and fired it to first, the throw would be right on the money,” Crowley said. “That’s because he was reacting to the ball, not thinking.

“Inversely, if the ball was hit right to Steve, it would give him time to think before he threw it to first base. Instead of just throwing, he would be thinking, ‘Where am I throwing? What am I doing? Where is my release point?’ ”

Dr. David Wright, a psychologist from Orange County who works with golfers on shaking their “yips,” simplified the human mind.

“The brain works in pictures, not in do’s and don’ts. If a golfer freezes up and shanks a putt, that is the last picture playing in his head. Even if he is thinking about what not to do, that is the picture playing in his head as he approaches his next putt, and that is how his body is going to react.”

“That’s exactly what happened to Sax in the ‘80s,” Wright said. “The only thing going through his mind as he wound up to throw was his previous errant toss.”

It all became a vicious circle: the more Sax thought about throwing, the more difficult it became for him to throw.

“Most coaches only see mechanics,” Crowley said. “And by trying to change a player’s mechanics, all it does is make that player think even more about their throw when in fact what they need to do is not think at all.”

“That’s why dealing with a player who has a case of the ‘yips’ is such a frustrating thing for a Major League organization to handle,” he continued. “They usually don’t know how to handle it.”

Luckily for Sax, the Dodgers had a manager and an organization that understood his mysterious malady.

At least sort of.

“More than anything, we just tried to remove pressure from Steve, as simple as that sounds,” said Claire, who served as a Dodgers executive from 1969-1998.

“We didn’t over-stress. We just tried to go about the daily routines of normal fielding drills,” Claire said. “And I think Tommy [Lasorda] was the perfect manager for all of that. He really had a bit of a light-hearted approach about it.”

Claire noted that the Dodgers’ organization never hired any therapists or psychologists to help Sax through his issues. Sax chose to work with Crowley on his own.

“Steve operated at a high emotional level and we didn’t want to increase that level,” said Claire. “So we never brought in any help for him. I think us stressing over his problem, would have only led to him stressing even more about it.”

Though other Dodgers players were aware of Sax’s issues, Claire said most of them had a pretty good attitude about it.

“I remember one time a reporter asked our third baseman, Pedro Guerrero, what goes through his mind before a ball is hit. His response was, ‘I hope they don’t hit it to Saxy… I hope they don’t hit it to me either!’ ”

“That was more of a jab at his own lousy fielding, not at Steve,” Claire said with a laugh.

To help Sax, Crowley urged him to become aware of positive, negative and neutral images that entered his mind. Once Sax was aware of these images, he could then tune out the negative ones by focusing intently on the positive or neutral ones. This is a practice Crowley calls “removing the clutter,” and one he writes about extensively in his book, MentalBall.

“Really what I did with Steve was got him to stop thinking about all the other ideas, suggestions, and theories everyone else was feeding him,” Crowley said. “Those just caused even more clutter and confusion in his already vulnerable mind.”

Another key component: the Dodgers never lost faith.

“Steve always contributed offensively,” said Claire. “He might have thrown the ball away and put a runner in scoring position, but the next inning he was just as likely to hit a double and score the runner from first base.”

“I think the fact that we still played him at second base every day helped him get over it,” Claire added. “He wasn’t reflecting on his previous performance for four days, like a pitcher would.”

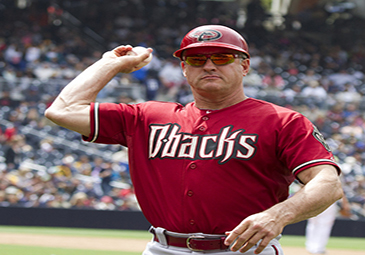

Sax would retired after the 1994 season, but returned to baseball in 2013 when he signed as the first base coach for the Arizona Diamondbacks. He did that for a year and now is back with the Dodgers, helping out the team’s community relations efforts.

Although he was able to save his baseball career, Sax is apparently still haunted – more than 30 years later – by his yips. A few days after agreeing to an interview, Sax backed out. He said he “did not want to re-live bad memories.”