Conquering a New Frontier

Graduate student Aileen Uy says her travel itch doesn’t jibe with being tied to a university campus.

So the 33-year-old Los Angeles native indulged her wanderlust while enrolled in USC’s online Master of Social Work program, which launched in 2010.

“I wanted the comfort and flexibility of being able to log into class while I'm in Denver or to do a presentation while I'm in Thailand or, even more so, being able to have all my study materials while I'm in Canada,” Uy said. “That's actually how I spent my first year as a grad student.”

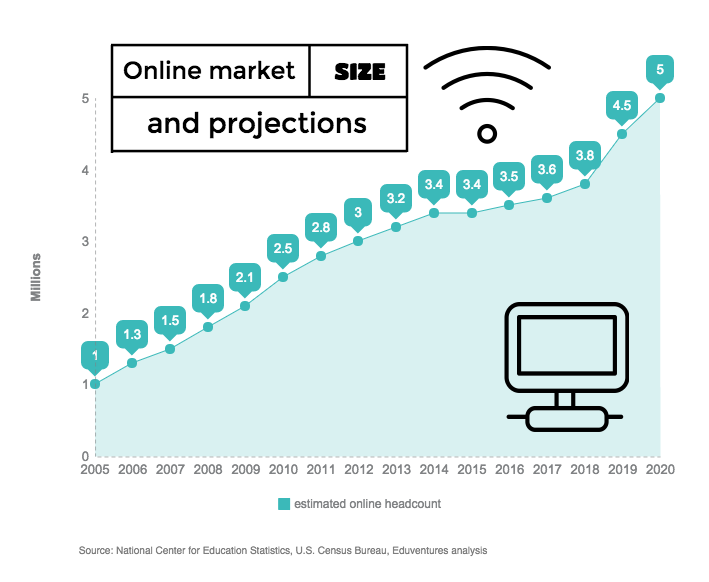

Uy is one of an estimated 3.4 million Americans enjoying the convenience and flexibility of studying online in 2015, up threefold since 2005. That’s 15 percent of all higher education enrollments, according to an analysis of National Center for Education Statistics data done by Eduventures, a higher education research firm.

Now universities from Yale to Arkansas State have set forth to capture the market of adult learners as a crucial survival strategy going forward, tapping into the business savvy of the for-profit sector in order to compete.

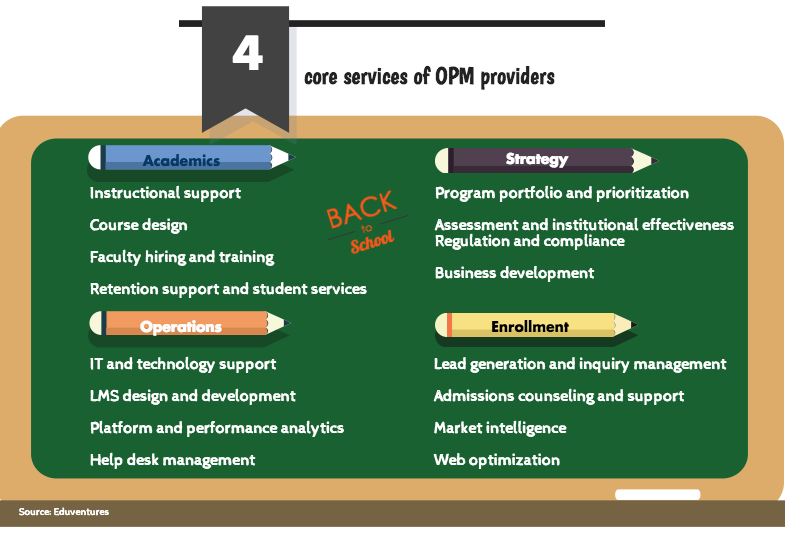

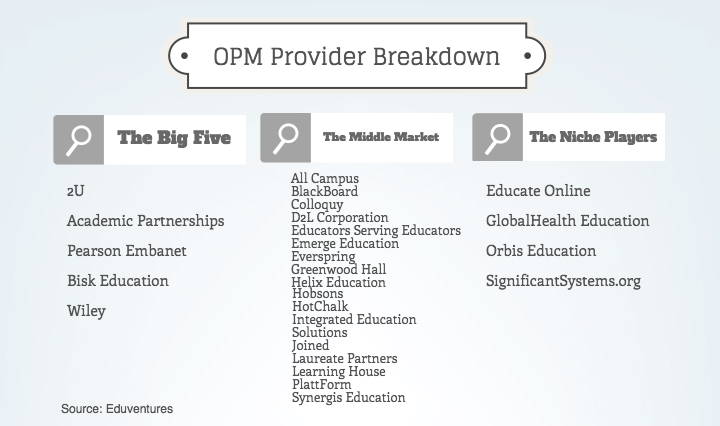

Aileen Uy discusses how online education fits into her life as a working adult.Online program management (OPM) companies are now behind the scenes at major institutions across the country, taking care of digital marketing, recruitment, tech support, and student support services. By this year, these education subcontractors are doing an estimated $1.1 billion in business and are expected to double their revenues by 2020, according to Eduventures.

Such partnerships, numbering around 350, have raised concerns that emphasis on growth, revenue, and cost efficiency could undermine academic quality and standards.

A thorough and transformative education just isn't a very cost efficient endeavor, says Cal State Stanislaus professor Steven Filling, who is chairman of the academic senate and a former board member of Cal State Online, which originally partnered with the OPM giant, Pearson Embanet.

“A lot of our students are first generation which means their parents didn’t go to college,” Filling said. “A lot of their parents didn’t go to high school. They don’t have much of an understanding of what it means to be in higher ed.”

“If you want to make profits, you want to look for, ‘Who will pay me the most for the least amount of work on my part?’ And obviously these folks are not the least amount of work. They are the most amount of work.”

But universities are currently struggling to become more financially efficient, experts say. “Institutions are realizing they need to do more with less,” said Eduventures Principle Analyst Max Woolf.

Higher education enrollment across the country has been in decline for four years straight, according to data from the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. The most recent research shows enrollment shrank 1.9 percent in spring 2015 from the year before — to just under 18.6 million.

Education analysts attribute the downward trend to decreasing sizes of high school graduating classes, a recovering economy, declining public dollars, and competition from alternative credentials such as coding boot camps, nanodegrees and professional certificates.

It’s forcing universities to rethink their long term survival strategy. “There’s a huge amount of schools saying, ‘if we want to stay in business, if we want to have a viable future, we have to think outside of the box we've been in for 50 years,’” said education analyst Phil Hill.

“There were well respected people in education and [public] policy making claims in 2011 and 2012 that by 2050 there would only be four universities left in the world and everything would be online,” said Filling. “Nobody wanted to be left out of that.”

A Partnership is Born

Education entrepreneur John Katzman found an opportunity amid a crisis.

Schools of education across the country were losing students at a rapid rate, down 30 percent nationwide from 2009 to 2013, according to data collected under Title II of the Higher Education Act.

California has been among the worst hit, with a 74 percent decline in teacher prep enrollment from 2002 to 2013, the latest year for which data is available.

Amid the downward spiral, Katzman received a call from Karen Gallagher, dean at the USC Rossier School of Education, requesting funding for a multimillion dollar chair in educational entrepreneurship, technology and innovation.

“I laughed at her,” said Katzman, who founded the Princeton Review before leaving the company in 2007 to start his next venture, an OPM provider called 2Tor.

“I said, ‘schools of ed aren’t the solution to entrepreneurship in education. They are about running a process that's been more or less the same for a couple thousand years — how we train teachers.’”

Katzman agreed to help fund the chair with $1.5 million of his own money on the condition that the Rossier school use it for something “disruptive, large, and impactful” wherever they saw fit.

USC Dean of Education Karen Gallagher on launching the first online degree at USC.“And so the whole idea of building an online MAT (Master of Arts in teaching) sprung out of that conversation,” he said.

Less than a year after the chair’s funding, the Rossier school contracted with Katzman’s then fledgling company, 2Tor, sealing a deal that brought students flooding into Rossier’s open arms.

“Since then we've graduated 2800 teachers,” Gallagher said. “Whereas if we were just doing the on campus program, we would have about 300 in that same time.” (video of Karen)

Katzman says Rossier’s decision to contact with his company was not related to his $1.5 million gift.

“I invested three million of my money and 12 million of other people's money into building and scaling up that MAT program,” he said. “It wasn't as if there were a lot of people with my background in for-profit education who were standing in line to invest that kind of money and who USC could trust to build something as scale and quality.”

2Tor, now known as 2U, receives a large share of the revenue since it funded the startup costs. A revenue sharing model that favors the OPM provider is the norm, as OPM providers take on much of the risk for universities which lack the “financial resources, the capacity to develop services from scratch, or the risk profile to take on brand new program expansion,” says Eduventures.

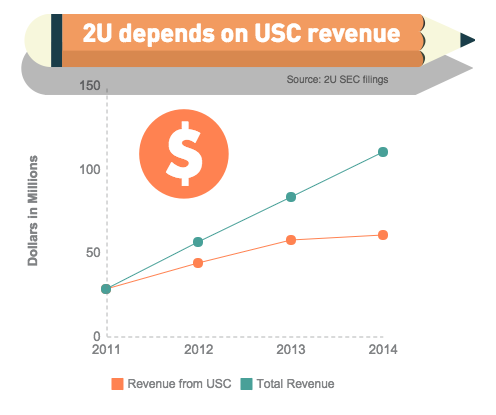

2U has since partnered with major universities including Yale, UC Berkeley and NYU, cementing its reputation among the OPM market as catering to an elite crowd, though it still relies mainly on partnerships with USC’s schools of education and social work, which launched in 2010, as a source of revenue.

Katzman left 2U in 2012 to start a new OPM venture called Noodle, which he believes will smooth out what he calls misalignments in incentives between for-profit companies and universities.

Katzman feels USC’s MAT program could have many more qualified students, if not for its high standards and relatively low cost compared with other programs 2U supports.

“The real incentive, when you have a bunch of programs, is to say, wherever I can generate the most profit, that's what ill do,” Katzman said. “The next dollar you spend in recruiting, you spend on behalf of the least selective, most expensive program you have.”

Massive Growth

Uy will amass “easily 100,000 dollars” in student debt upon graduation from her two-year online program at USC, where her classes range in size from six to 10 students.

Whereas 2U caters to expensive and exclusive schools, the other end of the spectrum includes OPM providers like Academic Partnerships, which specializes in online courses that can accommodate 1000 students and cost less with lower entrance standards.

“We tend to serve programs that draw very large numbers of students. Enrollment in the degree program will double, triple, quadruple over a matter of a few years,” said Daniel Smith, vice president of PR and communications at Academic Partnerships.

That model often relies on employing low cost academic coaches, a practice that has drawn some scrutiny from critics who fear a degrade in academic quality.

To alleviate professors’ workloads, coaches serve as teaching assistants who grade papers, answer student questions, monitor engagement, and sometimes facilitate course content. In plenty of cases, they are filtering into the ranks of the faculty.

Academic Partnerships works with a company called Instructional Connections, who hires the coaches. “Many students credit their coaches with their successful completion of a degree program,” the Instructional Connections website states.

Instructional Connections CEO Robert Williams maintains that the university exercises academic oversight. “We present coaches to faculty members and they select who they want,” he said. “In some cases, they interview them. In all cases they have complete control over who is selected and who is retained.”

Williams calls coaches a “low cost alternative to the adjunct model.” Instead of hiring more adjunct faculty to handle the growth in students, coaches take on the bulk of the workload for less pay. He says he currently employs over 1000 coaches and knows of no other company offering similar services.

The more students in a program, the more business for Instructional Connections. Williams says one nursing program the company works with has 3000 students. “We're like the Walmart of service providers because the larger numbers — that's how we earn our keep,” he said.

For many, serving as an academic coach is a good way to break into the teaching profession. Coaches typically have master’s degrees or Ph.D.s and field experience, but often no teaching background.

Kimberly Heien started as an academic coach for the University of Texas at Arlington in 2010. The school, which partners with Academic Partnerships, eventually asked her to join their online adjunct faculty. “That's happened to quite a few of our coaches,” she said.

The potential for upward mobility is the trade off for the not so stellar pay, she says. Heien still spends around five or six hours a week coaching for a five-week UT Arlington nursing course, earning $18 for each of her 30 students.

Years ago, coaches “complained about the low pay and were quitting,” said Heien. “I think the pay hasn’t changed but the faculty in the university have standardized everything within the courses. …So the courses run so smooth that it doesn't take as much time as a coach.”

Looking Ahead

The surge into online territory has some professors feeling they were left in the dust, including Jack Zibluk, former professor and president of the faculty senate at Arkansas State University, which launched its first online degree program in 2008.

He worries academia is losing its substance in the era of for-profit partnerships. “We're becoming more like a widget factory all the time,” Zibluk said. “If you were in a macroeconomic class, you would say well so and so is making X number of widgets per hour.”

Zibluk, who left ASU in 2012, feels he was not included in a deeper conversation about how ASU’s new approach to education would impact the university’s identity.

“We are becoming a business,” he said. “We are becoming more Academic Partnership and less Oxford. If we want that, that's OK. But what really irks me as a longtime faculty member is we don’t have a say in the matter.”

That’s because the university approaches the relevant department when launching an online degree program, says Thilla Sivakumaran, executive director of online A-State. In 2008, that was the school of education, whereas Zibluk belonged to the communications department.

“For example if we're launching a B.S. in strategic communications, we would approach the communication faculty and ask them, ‘would you be interested in launching your program?’ We wouldn’t make it a public announcement to campus.”

A-State is soon to launch an online degree in strategic communications. Strategic communications professor Holly Hall says the initiative was voted upon by faculty and approved.

As the OPM market expands, universities will continue to the confront the challenge of balancing efficiency with a fully-fleshed academic experience.

Filling says “we haven’t figured out yet” how to “do for education what Henry Ford did to car production.”

“Henry Ford is famous for using maximal use of assembly lines so the production of cars became incredibly efficient,” he said. “Instead of producing 10 cars a year, you could produce 150,000. Also standardization, so that when your tire went flat, you could go buy a standard tire and replace it. You didn’t have to get a tire custom fitted to that.”

“The problem is, it turns out education is a lot more complex than building cars.”

Evangeline Cummings, director of online programming, summed up the challenges faced by the University of Florida Online as it develops in-house services after ending its contract with the OPM company Pearson Embanet earlier this year.

“I look forward to our continued growth, but at the same time, it must be growth that we can sustain and it must be growth that is not at the expense of our students,” she said.

That’s what universities are having to think about as they join forces with the for-profit sector in order to survive and adapt to a changing landscape: how to grow in a manner that doesn’t sacrifice the heart of the academic institution.