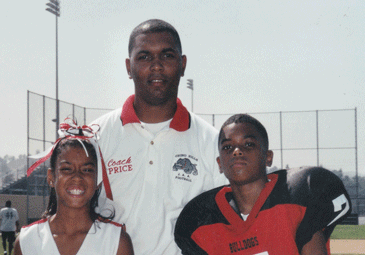

Jelani Gardner breaks the huddle before game action resumes. (Daniel Tran/Annenberg Media)

Jelani Gardner breaks the huddle before game action resumes. (Daniel Tran/Annenberg Media)

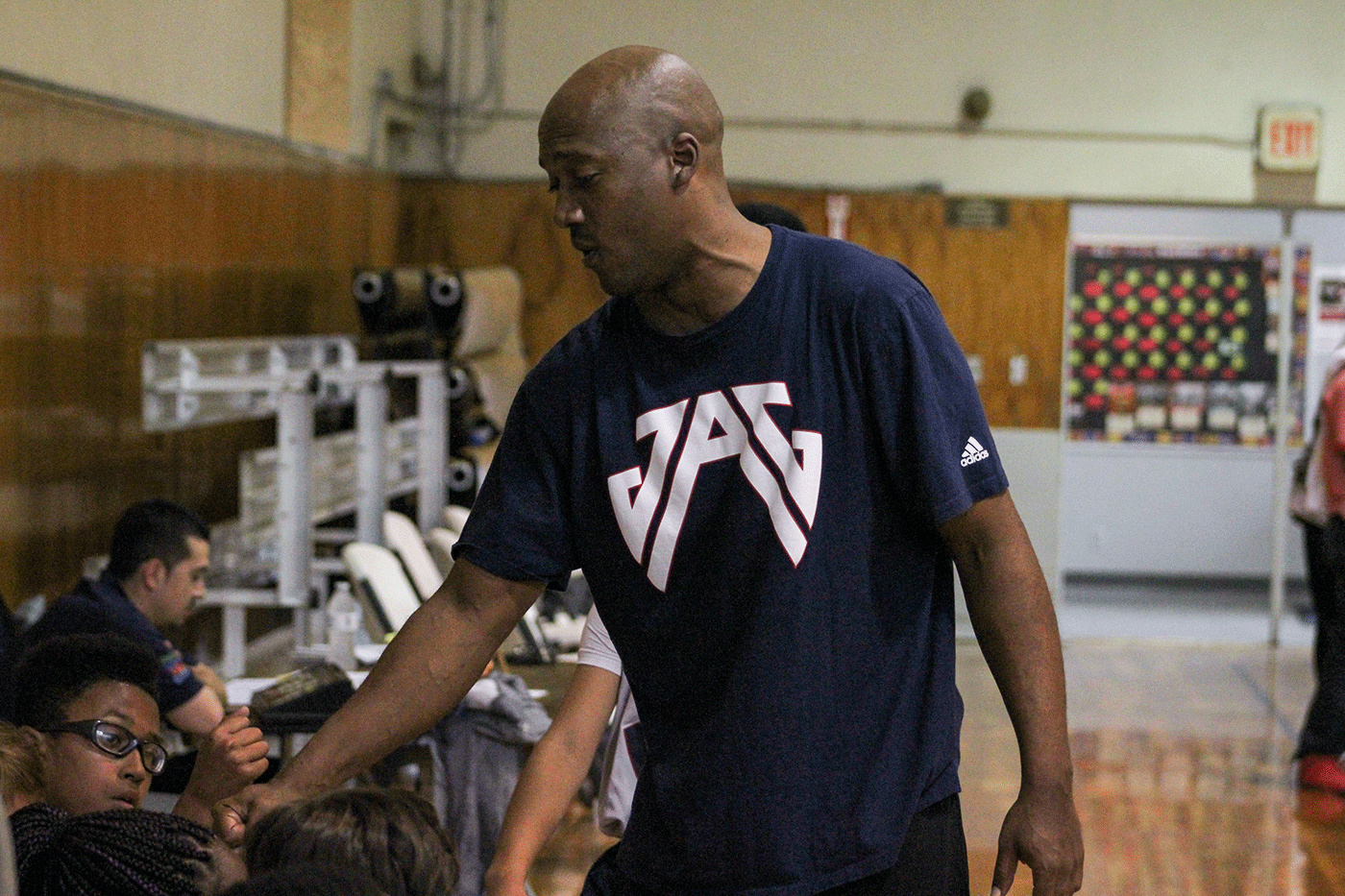

Jaiyon Gardner was hurting. The knot in his quad was already bothering him, but got worse after getting kneed in the thigh during a J.A.G. Youth Basketball practice in Pasadena, Calif.

Being a 9-year-old and playing high-level basketball is hard. But playing against 15-year-olds is an entirely different monster.

And although the physical challenges are tough for Gardner, the mental ones may be even more daunting.

Gardner has to remember the 2-3 zone, full court press, high-low, and the pick and roll offense. If he makes a couple of mistakes, he is going to hear about it from his coach – his father, Jelani Gardner.

Gardner is one of many parent-coaches in the United States. One 1998 study by E.W. Brown estimated that 90 percent of coaches in youth sports have coached their children.

Jazz Gardner goes for the opening tip. (Daniel Tran/Annenberg Media)

Jazz Gardner goes for the opening tip. (Daniel Tran/Annenberg Media)

More recent research in 2012 from John O’Sullivan in his book “Changing the Game” estimates that 75-80 percent of parents coaching youth sports end up coaching their own child.

For some parents, coaching their children allows them to spend time with their child and shape who they are as a competitor. They get to experience the thrill of victory and pick them up after defeat.

The most successful coaches know how to gauge their children’s ability and either foster their drive to compete or their desire to have fun.

Sometimes it isn’t all fun and games.

“You could play stupid if you want,” he yells at Jaiyon.

Gardner demands a lot of Jaiyon, not only because he plays point guard, arguably the most important position on the court, but because there are higher things at stake for the coach -- the future of his sons.

Gardner is the founder and head coach of his own youth basketball program. He played 13 years of professional basketball in Europe before moving back to the U.S. with his wife and children in 2011.

Not only does that mean that he gets to continue working in the sport that he loves, it also means he gets to coach his two sons, Jaiyon and Jazz, 11.

Jelani can be tough on his children, but both have expressed a desire to get better at basketball. He pushes them to be better with high expectations. When those expectations aren’t met, Jaiyon and Jazz will be held accountable, sternly or otherwise.

John Callaghan, a professor of Sports Psychology at the University of Southern California, says that at a young age, fun – not victory -- is what parents should be focusing on.

“The child wants to do well, but they don’t want that pressure,” Callaghan says. “They want to have fun, and that’s what sports should be about.”

Callaghan says that parents who coach their children are risking a breakdown of the family if they do a poor job.

A 2005 study by Maureen R. Weiss and Susan D. Fretwell published in “Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport" studied fathers who coach their sons. The study found that a common negative theme for players who played for their fathers was pressure to perform better.

Gardner expects his sons to try their best and have the game mold them into good men.

“The thing I want from my kids is to be mentally tough and men of character,” Gardner said. “Everybody goes through tough times, but we got to persevere.”

Gardner is all business on the court. If players make mistakes, there will be consequences. If there is a lack of focus, the guilty party gets an earful of instruction, push-ups and suicides – sprinting baseline to baseline.

He doesn’t worry about the soft-spoken Jazz, who rarely goes against the grain and is receptive to Gardner’s tough coaching.

Jaiyon is another story.

“He thinks he knows it all,” Gardner says. “He can enlighten people’s lives, but then he could be cocky and arrogant, so we’re trying to get the good habits to stay.”

Jazz and Jaiyon receive instructions. (Daniel Tran/Annenberg Media)

Jazz and Jaiyon receive instructions. (Daniel Tran/Annenberg Media)

Gardner yells and criticizes to try and get that message across. On the court, if Jaiyon shows frustration at a call and doesn’t give 100 percent effort, Gardner lectures him on the sideline before benching him. Other players also get an earful from Jelani, but his sons usually get the brunt of the screams.

The criticism does not end at the games, either. Car rides home are usually filled with talks about what happened during the game, and what could’ve been done better.

“I don’t really like getting talked to [after the game] because I want to do everything over again,” Jazz said.

Most experts sympathize with Jazz.

Larry Lauer, a professor of Sports Psychology at Michigan State University, says that parents should keep the game separate from the household. Keeping the two realms apart creates a clear line between “parent” and “coach.”

“Usually this conflict is due to the parent’s and the child’s inability to separate the coach and parent roles,” Lauer states. “Refrain from turning dinner table conversation to coaching critiques.”

Lauer implies that relationships can be damaged, and resentment can build, if parents do not know when to lay off their children. Callaghan plainly states it.

“I’ve seen it where parents think they are the next great coach, and often their demands are ridiculous,” Callaghan says. “The children feel that they just can’t do it because their parents are harassing them.”

Weiss and Fretwell asked fathers, sons and teammates about what parent-coaches can do to make the experience coaching on the field enjoyable for everyone. All parties stated there should be a clear separation between dad and coach.

However, plenty of parent-coaches take a different route, and some make it work.

Click here if video does not play.Rebecca Garcia coached her daughter, Frances, in basketball and volleyball until she was in high school. Frances was a target of harsh criticism when she didn’t have a good game, but she did not mind conversations after games on the ride back home.

Garcia also imparted sound advice during those talks with Frances. It was not just senseless yelling. She actually had knowledge about the game to impart. Was it loud at times? Sure, but it was meant to be constructive, she says.

Of course, it didn’t hurt that Francis was a fierce competitor. Sometimes, children crave the instruction after games, on the car ride, and at home, so they can improve. It’s hard to deny them feedback if that’s what they want.

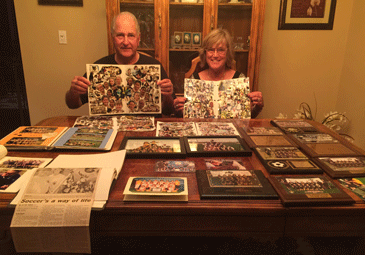

Bob Johnson, Mission Viejo’s Head Football Coach, has been in the coaching business for 45 years. He has coached his two sons and grandson. He says he never forced his children to do anything football related unless they pushed for it.

“I never brought football home,” Johnson said. “Did we ever throw on Saturday or Sunday? Yeah, but they’d have to ask me. It worked.”

Jaiyon Gardner playing tough defense.(Daniel Tran/Annenberg Media)

Jaiyon Gardner playing tough defense.(Daniel Tran/Annenberg Media)

He knew that his sons had a competitive drive that would bring them to him for extra work. He never had to drag them through extra sessions. He set up an environment where he helped them as long as they wanted to help themselves.

Johnson’s sons valued his understanding of football. That kind of knowledge of the game commands respect, and gives kids a better experience because of the insider information that it brings to the children.

Bret Johnson was the first to be coached by Johnson at El Toro High School in the mid-80s. He was not able to break into the National Football League at first, but after a stint in the Canadian Football League, he finally made it to the NFL in the mid-90s.

His brother, Rob Johnson, had more success in his football career. After starting for the University of Southern California, he was drafted by the Jacksonville Jaguars in 1995. He eventually won a Super Bowl in 2002 with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers.

Bret’s son, Brock, would be the latest in a long line of offspring to be coached by Johnson. Brock is the only quarterback in the family to win a state championship under the direction of his grandfather.

Not only was Johnson there to guide him, but so were his father and uncle. The combined knowledge of their coaching helped Brock achieve a goal that neither of them ever got during their playing days.

Another former player also coached his son to success not too far away in Chino Hills.

Dennis Price was a former National Football League player who had stints with the Los Angeles Raiders and New York Jets. After leaving the league, Price went on to coach his son, Sheldon, in football in 1999.

“It helped me give him some things that maybe the average dad who played up through high school didn’t have access to,” Price says. “He got to meet a lot of people that also gave him advice and instruction.”

He never had to push his son into football. Sheldon actually started in soccer, but he kept insisting to his dad that he wanted to play football. Price’s knowledge and desire to impart it to his son took over from there.

Both Prices have mostly good memories of the experience. Sheldon even credits his dad's coaching for the strong relationship that they have today.

Unless you’re a pro, a lot of parents need to learn games from scratch before coaching their children. That is what Nancy Nelson did for her daughters when she saw American Youth Soccer Organization coaches yelling at kids during games.

“I took a coaches clinic, an advanced coaches clinic, and I took a referee clinic,” Nelson says. “I learned the rules, I learned the game and I took a team because I wanted to see those kids having fun, and not being yelled at.”

Although her daughters were usually the best players on the team, Nelson believed that fostering a fun environment was the best way to get the most out of them and their teammates.

Fun isn’t a word that most people would use to describe a typical Gardner practice or game. Jaiyon, especially, has a tough time at some games if a call doesn’t go his way, or he isn’t playing hard enough for his father’s standards.

How does the family keep the peace?

The front door of their house.

Jaiyon taking a breather beside Jelani. (Daniel Tran/Annenberg Media)

Jaiyon taking a breather beside Jelani. (Daniel Tran/Annenberg Media)

Once they come home, Gardner dials down the “coach” and becomes dad. He may keep talking to make sure the points from the game are understood, but the yelling stops and he is the affectionate father that his kids love.

It seems to be working. Despite his tough standards, Jazz and Jaiyon don't mind that he's tough on them sometimes. Every year, they continue to want their father to coach them as they try to improve their skills.

“It gets me better,” Jaiyon says.

“He knows what I can do on the court,” Jazz says. “For other people, they’ll just put me as the big man that just stays inside. He lets me go outside, shoot threes, rebound and push the ball.”

Through all the yelling and criticism, Gardner still has the love of his sons even while pushing them to improve as players and men. Knowing their desire to compete allows him to do that as he balances his harsh words with tenderness.

Nothing is more evident of that than when Jaiyon cuddles up into the arms of his father as they watch basketball together as a family. Gardner strokes his son’s head with a gentleness that he never shows on the basketball court.

“I just want to be here for my kids,” Gardner says. “I’ve had my time. I just want to be a good father and a husband.”