Frances Garcia was a star athlete growing up, eventually earning a volleyball scholarship to play at the Division I level at Gonzaga University.

She credits her mother, Rebecca Garcia, who coached her as a youth, for helping her become a successful player.

What’s more, Frances’ relationship with her mother was able to withstand the pressure and stress of competition. It wasn’t perfect, but looking back Frances appreciated her mother’s coaching.

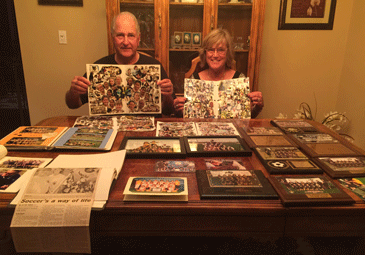

Team photo with Rebecca Garcia (top left) and Frances (bottom left). (Rebecca Garcia)

Team photo with Rebecca Garcia (top left) and Frances (bottom left). (Rebecca Garcia)

“If you asked me when I was playing for her [if the experience was enjoyable], I think my answer would be different,” Frances said. “Overall it was a really good experience.”

For Frances, playing for Garcia was not easy at times. Garcia was a tough competitor, and expected the best from her daughter. And, sometimes the coaching did not stop once the game was over.

Many academics and parents stress the need to separate what happens on the field from what happens at home. As many note, the lack of distinct lines when coaching your child can cause a rise in the pressure to perform. At times, this results in resentment between the parent and the child.

“Best Practice for Youth Sport,” written by Robin S. Vealey and Melissa A. Chase stated that pressure can work against players who are being coached by a parent. The book also says that parents should clearly distinguish the parent and coach role for a better experience for both the child and the parent.

However, results can make the criticism easier to swallow.

Frances recalls one particular match before she was in high school.

“All of the girls that we were playing against were playing club volleyball at the time, and I was the only one in my school playing club,” Frances said. Club teams are youth squads that come with a high fee for professional coaching.

Being the only one on her school team that had club training didn’t matter to Frances or her mother. More often than not, their team would end up defeating teams with the better-trained players.

Click here if audio does not play.“To come out with that victory, it was amazing,” Frances said with a smile. “Hearing your name called in the morning announcements, and ‘congratulations to coach Garcia,’ it was nice.”

Frances got her competitive fire from her mother, who played multiple sports growing up in the Philippines. She would even play against boys where she knew she was going to have a difficult time.

Click here if audio does not play.Those old school training sessions weren’t the only thing that Frances and Garcia clashed on.

As Frances rose through the ranks, differing approaches would cause friction between the two that would manifest into arguments. Frances was getting better at her craft, and like most teenagers, felt she knew more than her mother.

“Because I was playing club, I would try to apply the things that I learned,” Frances said. “She could only coach as far as she knew.

“I have to coach my mom now. I have to tell her this play doesn’t work. That was really hard. Having those arguments was very difficult,” said Frances.

The coaching never stopped when they left the court. The parent-coach and the daughter-player would share rides home where Garcia could not help but continue to coach Frances in the car.

Frances, however, needed those conversations to unleash her frustrations about the game.

Click here if audio does not play.There is no better evidence that Frances is Garcia’s daughter.

It is that shared competitiveness that holds their relationship together, and keeps it from splintering even when things get heated. That is what being a family is all about for this duo.

“We always stayed together,” Garcia explained. “If we played two games in San Diego, it would be a vacation. Everyone goes together.

“That’s the support part of it. We’re going to get mad at each other, but we’re going to get through it.”

Even today, as they arrive and leave the interview, they do it just as they did those games many years ago.

Together.