The Cut Man: Chris Ray

Chris Ray at home in Washington, D.C. A former fighter himself, Ray is an Army medical technician by trade. (Anne Branigin, Annenberg Media)

Chris Ray at home in Washington, D.C. A former fighter himself, Ray is an Army medical technician by trade. (Anne Branigin, Annenberg Media)

“Look at the corner.”

That’s what Chris Ray, the “cut man” says to do.

He’s at the Belasco Theatre in Downtown L.A. watching the main event: a fight between Brazilian Patrick Teixeira and American Don Mouton. After a heavy-hitting first round, Mouton — a power puncher — struggles to do damage against a taller, faster and more skilled Teixeira.

“He’s confused,” Ray says of Mouton. “Look at him.”

Ray has worked many corners. As the cut man for several notable fighters, including former light heavyweight and middleweight champion, Bernard Hopkins, Ray is responsible for stopping a fighter’s swelling and bleeding. So naturally, when Mouton lurches back to his corner, Ray notices something missing.

“Look at his trainer,” says Ray, his eyes bearing down at the man kneeling in front of Mouton, applying liberal amounts of Vaseline to Mouton’s eyebrows and cheekbones. In fact, the trainer seems to be the only man with Mouton, while a team of three attends to Teixera.

“He doesn’t have a cutman! He’s supposed to be trying to psych his fighter up,” says Ray. “He’s doing too much.”

Ray, on the other hand, could never accuse himself of doing too much. He does one thing, and he does it very well: keep his fighter’s eyes open.

“I never met a cut I didn’t like,” says Ray, an Army medical technician who’s spent twenty years working the corners at boxing matches. He keeps a fighter in the match by mitigating the swelling and bruising around the fighter’s eyes and stopping any bleeding. Unchecked, these injuries can obstruct a fighter’s vision and affect how he observes and responds to his opponent.

But having a good cut man can also give fighters the confidence they need to keep their head in the match, says Ray.

“Fighters can see blood dripping in their eye, and some of them will just quit,” says Ray. “While he’ll come to the corner with an experienced cut man, and [the cut man] will do what he gotta do. Stop the bleeding, and he gets right back out there. It’s the mark of a champ.”

Ray also points out that relying on a strong cut man means a fight is less likely to be decided by the ring doctor, who can stop the fight if he sees a fighter has taken on so much damage he is unable to continue fighting.

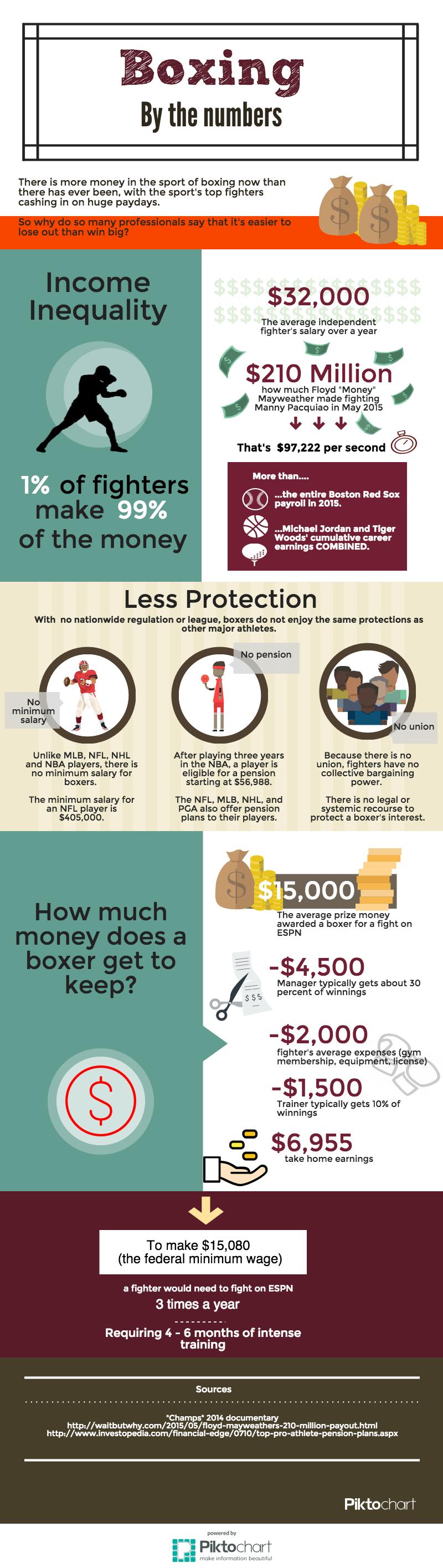

While many boxers find the skills of a cut man invaluable, it’s not a lucrative profession. The cut man typically only makes 2 to 5 percent of a fighter’s purse. An ESPN bout that awards a fighter $15,000, then, only nets a cut man $300 to $750. Depending on the arrangement, this payment can either come from the fighter or from the trainer’s cut. So, when Ray sees a corner without a cut man, he typically chalks it up to a trainer’s greed.

"Most fighters want to hear one voice in that corner, and that's the voice that you heard all the way through training camp, and that's the lead trainer,” says Ray.

"I have nothing to say, I let my equipment do the talking for me."

Ray shares his tools of the trade

The Trainer: Edmond Tarverdyan

Edmond Tarverdyan, left, spars with Arif Magomedov. Tarverdyan is preparing Magomedov for his first HBO bout, scheduled for December 12 at the Glendale Civic Auditorium. (Anne Branigin, Annenberg Media)

Edmond Tarverdyan, left, spars with Arif Magomedov. Tarverdyan is preparing Magomedov for his first HBO bout, scheduled for December 12 at the Glendale Civic Auditorium. (Anne Branigin, Annenberg Media)

When Edmond Tarverdyan watches his fighters spar, he looks like a chess player deciding his next move.

He cups his face in one hand, watching how the fighter sticks his combinations, whether the fighter’s hands spring back to his face, as vigilant in defending himself from an attack as he is in launching one.

“I love to solve problems,” says Tarverdyan. “I look at a fight as a big problem.”

Tarverdyan has been working with fighters for almost twenty years. He began at 16 years old, and has trained both boxers and mixed martial arts (MMA) fighters, including Ronda “Rowdy” Rousey, the fighter credited with putting women’s MMA on the map.

The myriad ways one can beat — and can be beaten by — an opponent is one of the reasons why Tarverdyan loves training. With each fighter, he devises a game plan, tries to play to the fighter’s strengths, mitigate their weaknesses, and anticipate what the opponent will do.

One boxer he’s currently training is Arif Magomedov, a Russian who will be fighting his first HBO bout on December 12th. To get him ready, Tarverdyan needs to help his fighter adjust to American professional boxing, which tends to reward aggressiveness.

Magomedov fights with a "Soviet Union style," meaning his punches are very accurate, says Tarverdyan. To get him ready for professional boxing in America, Tarverdyan wants Magomedov to be more aggressive with this shots. (Anne Branigin, Annenberg Media)

Magomedov fights with a "Soviet Union style," meaning his punches are very accurate, says Tarverdyan. To get him ready for professional boxing in America, Tarverdyan wants Magomedov to be more aggressive with this shots. (Anne Branigin, Annenberg Media)

“He has the Soviet Union style of fighting. The discipline. Their boxing skills are a bit different,” says Tarverdyan.

“I'm looking for more volume and punches. I'm looking for consistent combinations. I'm looking for him to settle down a bit in his combinations and sit down on his legs a little bit more,” he says.

While Tarverdyan understands — and loves — the challenge of training a fighter, he wasn’t always in a position where he could earn a living this way. Tarverdyan used to manage fighters, and co-owns a promotion company, Lights Out Promotions, that showcases MMA fights.

He knows firsthand that, on the way up the ladder, it’s much easier to lose money than it is to make it.

“I've lost a lot of money managing fighters and training fighters and keeping the gym doors open,” says Tarverdyan. “My fighters don't pay a gym fee. They train for free and if you look at them, the roster, you have one fighter, two fighters that makes the real money. And how about the rest? You spend so much money and so much time on them and they don't make any money realistically. It's a difficult business.”

For Traverdyan, one of those fighters would certainly be Rousey, whose name and likeness can be found throughout Glendale Fight Club. Her signed gloves hang over the boxing ring, her articles and photos are framed near the front of the door, there is even an oil painting of her grappling with an opponent hanging on the gym walls.

Once a trainer can build one champion, the opportunities to create another begin to multiply.

With Tarverdyan, his eyes are set on preparing Magomedov to enter the next phase of his career. Already, he’s aiming at the top of the division, choosing Magomedov’s opponents carefully so that he can be ready to face Andy Lee, the current middleweight champion.

Tarverdyan already has Andy Lee, the current middleweight champion, in Magomedov's sights. He hopes to have his fighter ready for a championship bout by next year. (Anne Branigin, Annenberg Media)

Tarverdyan already has Andy Lee, the current middleweight champion, in Magomedov's sights. He hopes to have his fighter ready for a championship bout by next year. (Anne Branigin, Annenberg Media)

“I can't baby him just so he can be exciting on TV that night and we can make some more money,” say Tarverdyan. “Then get him into a world title shot and not be able to deal with it.”

Which is why, for this next fight — the biggest of Magomedov’s career so far, both in terms of audience and scale — Tarverdyan says the mental preparation will be as important as the physical preparation.

“It doesn't matter who's watching you. You have to stay mentally disciplined and focused,” says Tarverdyan. “This is a fight. Doesn't matter if the crowd is booing you, cheering you on, things like this could happen. You know and you shouldn't lose focus, because losing focus in the ring — you lose your head, you lose your ass.”

The Manager: Egis Klimas

Egis Klimas embraces his fighter, Sergey Kovalev. Klimas warns that the biggest mistake a manager can make is to treat his fighter like an ATM. (Rich Graessle, Main Events)

Egis Klimas embraces his fighter, Sergey Kovalev. Klimas warns that the biggest mistake a manager can make is to treat his fighter like an ATM. (Rich Graessle, Main Events)

“If you look at my credit history, you’re probably going to find like, 11 cars,” laughs Egis Klimas. “I just finished co-signing another car for one of my fighters.”

These 11 cars are less a testament to his generosity, than a strange byproduct of his profession. Klimas is a manager who’s shepherded the careers of several prominent Eastern European fighters, including Sergey Kovalev and Vasyl Lomachenko, both titleholders in their respective divisions.

These fighters come to America with dreams of champions — and with no credit history. Which is where managers like Klimas come in.

Klimas boxed a little when he was younger, but his love for boxing really took off after he moved to the United States from Lithuania in 1989, when he became enthralled with the heavyweight boxers of the era.

“Larry Holmes, Mike Tyson, Evander Holyfield, Riddick Bowe. I really liked that sport. I was going to matches, I was buying the pay-per-views,” says Klimas. It was this interest that eventually led him to start managing fighters.

Because managers typically take the largest share of a fighter’s earnings — upwards of 30 percent — and because they’re typically the ones negotiating a fighter’s contracts, many people associated with boxing will blame the manager for a fighter’s financial problems.

But trainers and managers know that — particularly without a major promotion company, like Top Rank or Golden Boy — a lot of the overhead costs of supporting a fighter is put up by the manager, who acts as the fighter’s first investor — and ATM.

Klimas, like the Armenian Tarverdyan, attracts a lot of Eastern European fighters due to his background. Because of this, his job as a manager not only includes finding sponsors for his fighters, but acquiring visas and cosigning on cars.

However, he jokes, he’s also been able to avoid some of the typical challenges a manager faces because of this.

“You meet a lot of people, we’d call them ‘locker room lawyers,” says Klimas. “The fighters are always listening. 'Well, these guys aren't paying you enough. You have to go here, if you come here I can help you.' I didn't have that problem because my fighters didn't speak English. So nobody could get into their heads.”

Klimas maintains that his relationship with his fighters is what separates him from other managers who may look at their fighters as a payday.

“I think the biggest mistake is when you’re looking at the boxer as a money-making machine, which a lot of people in boxing, they do that. As soon as they see a good fighter, they start thinking about money, instead of thinking, what I can do for the guy to make him famous,” says Klimas. “They are looking at the fighter and milking the fighter right from the beginning.”

Klimas says the responsibilities of a manager are endless. There’s the paperwork and the boxing licenses. Figuring out where a fighter will train and live, who will train him and who will feed him. And because Klimas deals with so many foreign fighters, the tasks multiply.

“Every fighter is different as a personality. Every single one wants your attention. You have to spend the time to each of them,” he says.

“Especially if a fighter's coming from the former Soviet Union, they come here like blind little cats,” says Klimas. “They don't speak English. They don't know what to do. I have to deal with getting their social security number, getting their licenses, getting their bank accounts.”

Then there’s the equipment — the boxing shorts, the gloves, the shoes. All of which Klimas takes care of.

“I can probably name every single of my fighters right now, what's their shoe size,” says Klimas. Because of how involved — and how personal — his relationship with his fighters is, Klimas’ measure of success may seem different from a typical manager’s.

“They build already their credit history. They already start purchasing on their own. They start renting a house on their own. Wow,” says Klimas. “This is success.”

The Fighter: Adrian "Turtle" Carrion and Jessie Vargas

The most important part of having a successful team, according to Klimas, Tarverdyan and Ray, is that everyone knows their role — and executes it.

Adrian “Turtle” Carrion is among the fighters who have attempted to promote themselves. Carrion felt pushed to do this after feeling shorted by a local L.A. club promoter who was paying his opponent more than he was paying him.

“The contract was signed right in front of me. I saw the contract and he just ripped it out of my hands. He goes, if you don’t like it, don’t fight. But I had already sold over 500 tickets, so I couldn’t let my people down,” says Carrion.

“He challenged me and said if I thought it was that easy I should just do it myself. So that's what I did.”

But even though Carrion is proud of his success as a promoter — he maintains that in less than a year, he took over the business of the promoter who had shorted him — he acknowledges that managing yourself as a fighter is unwise.

“As a fighter, to manage yourself, it’s kind of hard. Once you get a good team to help you out, you got your attorneys who can negotiate all your business for you, it gets easier. But when you start, you need to focus on just one thing, and that’s winning the fight.”

Jessie Vargas, a former light welterweight champion, emphasizes trust.

“Anyone that can benefit from you, or can see themselves benefitting from you, and also people who think they can help you. You have people all over the place,” says Vargas.

So when he teamed up with manager Cameron Dunkin, Vargas had already known him and been watching him for years.

"I look at his history. I look at what he's done for fighters,he relationship that he keeps with the fighters that he helps, and I liked that,” says Vargas. “That's when I wanted to be connected with him.”

Vargas, 26, who considers himself in the prime of his career, says he’s still getting a hang of the business side of boxing.

“Any athlete needs to know the business side of the game. I understand that we love this sport, but it's also a business and we need to inform ourselves more about the business,” says Vargas, who adds that one of his concerns is whether “the numbers make sense.”

Jessie Vargas lands a punch against Anton Novikov (left). (Chris Farina, Top Rank.)

Jessie Vargas lands a punch against Anton Novikov (left). (Chris Farina, Top Rank.)

Most people say that ultimately, longterm success and longevity will rest on the fighter’s shoulders.

“As a fighter, the only thing you know is about fighting and that’s it,” says Carrion. “In life, you got to take chances. It’s part of the business, but some fighters get screwed over and you got to learn. And it’s tough. You need to try to connect yourself with the right people.”

“You got to have someone that’s going to take care of you.”