Among female screenwriters, Adele Lim, Ligiah Villalobos and Geneva Robertson-Dworet are a few of the "lucky" ones.

Among the three of them are:

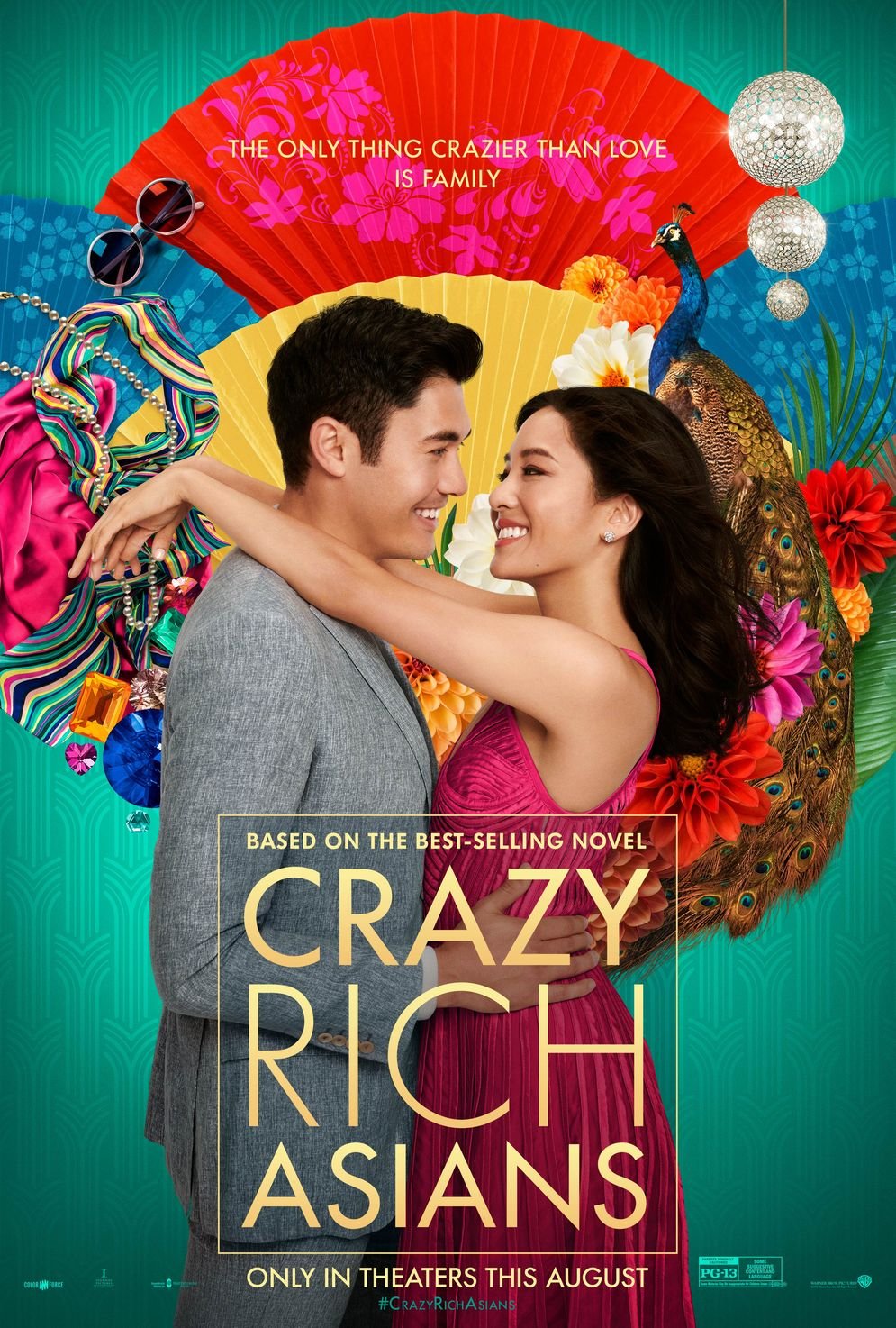

- Not only the highest-grossing U.S. film with a predominantly Asian cast in history but the most successful romantic comedy in a decade.

- The highest-selling Spanish-language film to ever be purchased at Sundance in addition to the biggest box office hit in the history of Mexico.

- The highest-grossing female superhero movie of all time, not to mention the only such film to take in $1 billion.

These films found mainstream success thought to be unlikely for films centered around minority protagonists and cultures. But even with barriers crossed and records broken, talents are never quite proven and second chances are never quite guaranteed when there's a woman's name in the credits.

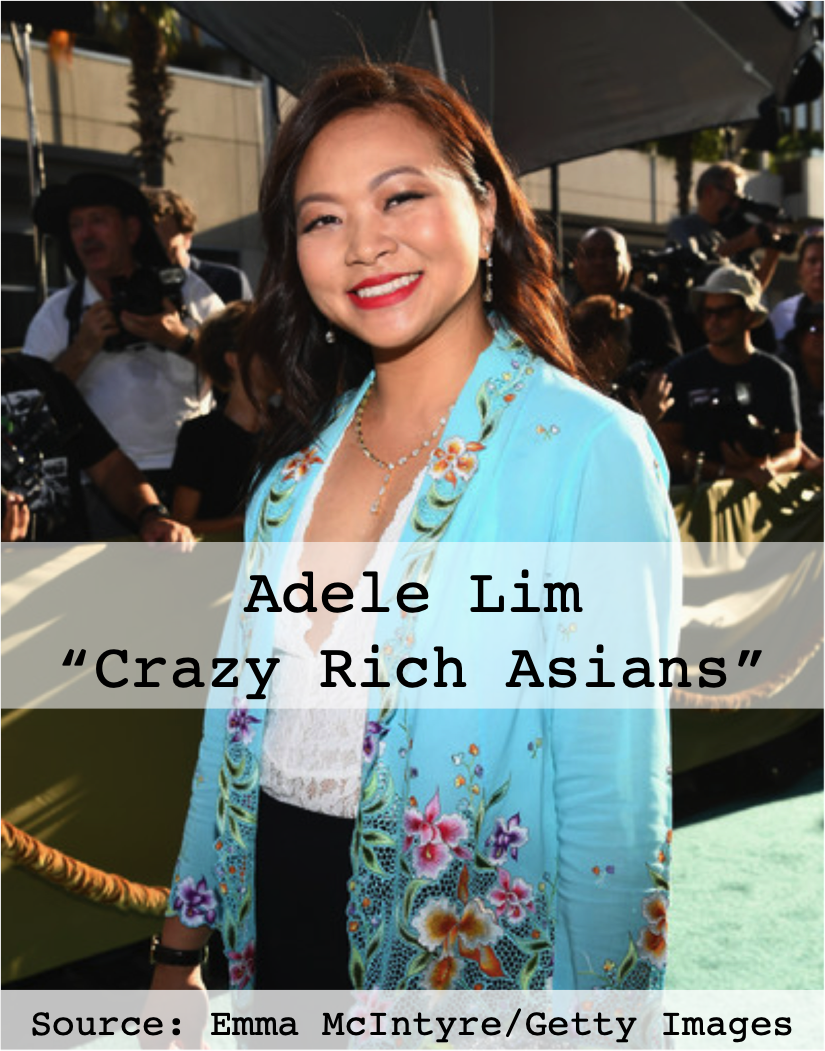

Adele Lim

"I mean we didn't have money, but the 'crazy' was definitely there."

Adele Lim was born in Malaysia to Chinese parents. Throughout her upbringing, she experienced the rich culture, stark class divisions and complex family dynamics that would come to inform the hit 2018 film "Crazy Rich Asians" firsthand. She just wouldn't be able to use them for a while.

Convinced that she would become an ad copywriter just as her parents did, Lim never thought she would work in entertainment, even once she moved to the United States for college.

"I met a boy who said he was going to write for TV," she said. "I didn't know it was an option."

The two aspiring screenwriters drove out to Los Angeles in the early 2000s, where Lim got a gig as a writer's assistant at "Xena: Warrior Princess." She went on to write for several TV shows including "One Tree Hill", Life Unexpected" and "Reign."

For 16 years, Lim was focused on cultivating a career within the notoriously fickle industry, not disrupting it. This meant writing for shows that had almost exclusively white casts.

"You just felt lucky to be there," she said. "You don't want to be the lady police or the brown people police. You want to be the writer that's just coming up with great stories."

Her seniority was rising and her IMDB page was growing, yet Lim sometimes felt that her voice wasn't valued in the writers' room, especially on comedic shows. Whether it was because she didn't go to the same elite colleges, worship the same movies or simply look like their friends did, Lim said, some colleagues would deduce that she just wasn't funny.

"A writer would just say it to your face," she said. "You can't fight the 'you're not funny' thing. It's like what are you going to do? Be funny on the spot?"

While some showrunners were more "woke" than others, Lim said, she ultimately realized that she had a wealth of cultural experiences that she was not getting to apply to her work.

"There is this feeling of not wanting to make a big deal of what makes you different," she said.

"I do think that's one of the extra hurdles that people of color do have to face in terms of writing because the best stories come from a true place."

Enter Jon M. Chu.

Lim had sold a pilot with the filmmaker a few years back and now he was looking to adapt a beloved novel called "Crazy Rich Asians" for the big screen.

"Jon really felt strongly that the book and the material were just so specific culturally," Lim recalled. "It was a female Asian point of view, so he wanted a female Asian American writer."

The book, written by Kevin Kwan, was a New York Times bestseller. It was unknown whether the property would find such universal success in film, where budgets and expectations are far higher.

A draft had already been written by veteran film screenwriter Peter Chiarelli by the time it passed into Lim's hands. It was to be her first movie. The daunting task became less daunting when Lim took on Kwan's personal philosophy: to write from a place of joy.

"It's so easy, especially with a property called 'Crazy Rich Asians,' for it to just be about a bunch of zany Asian people spending a ton of money and acting like assholes," she said.

For Lim, writing from a place of joy also meant writing from a place of empathy. This was especially true in regard to the character of Eleanor, who is extremely reluctant to let her son marry a woman who is neither Chinese-born nor a socialite. Lim explained that, in other films, Eleanor would've been written as an outright villain rather than a woman who simply loves her son.

"Here there is this feeling that once your child hits this age of maturity, there is this independence whereas with the Asians it really is that your family is a big part of who you are and your happiness. In Western storytelling, it tends to be either-or."

Lim's understanding of Asian cultural norms enabled her to present a more nuanced take on a conflict that many families struggle to reconcile with.

"You can't write from a place of being an 'other,'" she said. "That's when it feels like a movie about an 'other' as opposed to a culture just celebrating itself."

This celebration of culture resonated with viewers within and outside of it. "Crazy Rich Asians" grossed roughly $240 million worldwide.

Still, Lim is maintaining a sense of cautious optimism for future Asian representation in film, citing the last (and only other) film with an all-Asian cast thought to have been a watershed moment: "The Joy Luck Club"(1993).

"There was this expectation that it would change things for Asian writers, directors, actors. It changed nothing," Lim said. "Just because 'Crazy Rich Asians' did well does not mean that it's opened the floodgates."

Lim believes that the only way that change can be sustained is if the "white liberal dudes" at the top stop hiring writers similar to them out of comfort and convenience.

"If you don't have content creators who are women or people of color, you're not going to get this kind of content."

Ligiah Villalobos

"There is this belief in Hollywood that what Latinos want to do is just assimilate. I personally don't believe that that's true."

If you've seen one of the relatively few Latinx-centric TV shows or movies in the last 20 years, chances are that Ligiah Villalobos had something to do with it.

Beginning as a receptionist at an ad agency, Villalobos worked her way up the entertainment corporate ladder to run all television programming for the newly opened Latin American division of the Walt Disney Co. Disney eventually put her in charge of the company's writing fellowship program, yet it was her own talent that was eventually recognized.

"A couple of my writers kept saying, 'You really should be a writer, you shouldn't be an executive,'"she said. "When I asked them why they said, 'Because you give notes like a writer.'"

Villalobos initially dismissed their words of encouragement. She had never written creatively before, let alone written a script. Eventually, the "what ifs"in the back of her mind were loud enough for Villalobos to give writing a try.

"I took a creative writing class at Santa Monica College for $69 and it changed my life,"she said.

By 2001, she had written her first screenplay. Titled "La Misma Luna"("Under The Same Moon"), it was the story of a young boy trying to cross the U.S.-Mexico border in the hope of reuniting with his mother.

The script sat on a shelf for years as Villalobos racked up her first writing credits. In 2005, she became the head writer of Nickelodeon's "Go, Diego, Go!,"a spinoff of "Dora the Explorer."

Her passion project, however, regained traction in 2006. Funded half with American money and half with Mexican money, "La Misma Luna" was shot in just 25 days.

The film nabbed a coveted slot at Sundance Film Festival in 2007, where it was purchased by an American distributor. It was the biggest sale of any Spanish-language film in Sundance history. Once it was released to the public, "La Misma Luna" took in 10 times its budget in ticket sales.

Villalobos, a Mexican immigrant herself, said the film's subject matter felt personal to her. However, she did not want the film to be about immigration.

"I see immigration in the film as the plot of the story," she said. "What I wanted to really explore thematically in the movie was about abandonment."

Villalobos has been trying to convince studio executives of the universality of her and other Latino American filmmakers'stories for years. Myths regarding the supposed low profitability of films told from Latinx perspectives, especially Latina perspectives, persist.

"In the case of American Latino filmmakers, it is almost impossible to get our stories told," she said, "even though we represent the biggest minority population in the country."

That's 17.6% of the U.S. population to be exact, according to 2015 U.S. Census Bureau data.

Villalobos believes that this disconnect on the part of Hollywood executives stems from misinformation about what Latinx audiences want: films that aren't all about ruthless drug lords and fiery sexpots.

"Seventy-one percent of opening weekend (ticket sales) for my film was actually Latinos," she said. "I believe that if good programming comes our way, we will go support those films. It's not because people don't want to see it. It's just that there's such a lack of product that really understands what we want as an audience."

A combination of quality programming and behind-the-scenes authenticity produced Pixar's "Coco"(2017), which grossed over $800 million globally. Villalobos, who served as the film's cultural consultant, believes that its success is a testament to both the artistic and financial value of diversity.

"You cannot get more specific in terms of culture than 'Coco.' It is as Mexican as you can get," she said. "It's not that our stories aren't universal. It's just having a studio or a network that is willing to keep trying to get it right."

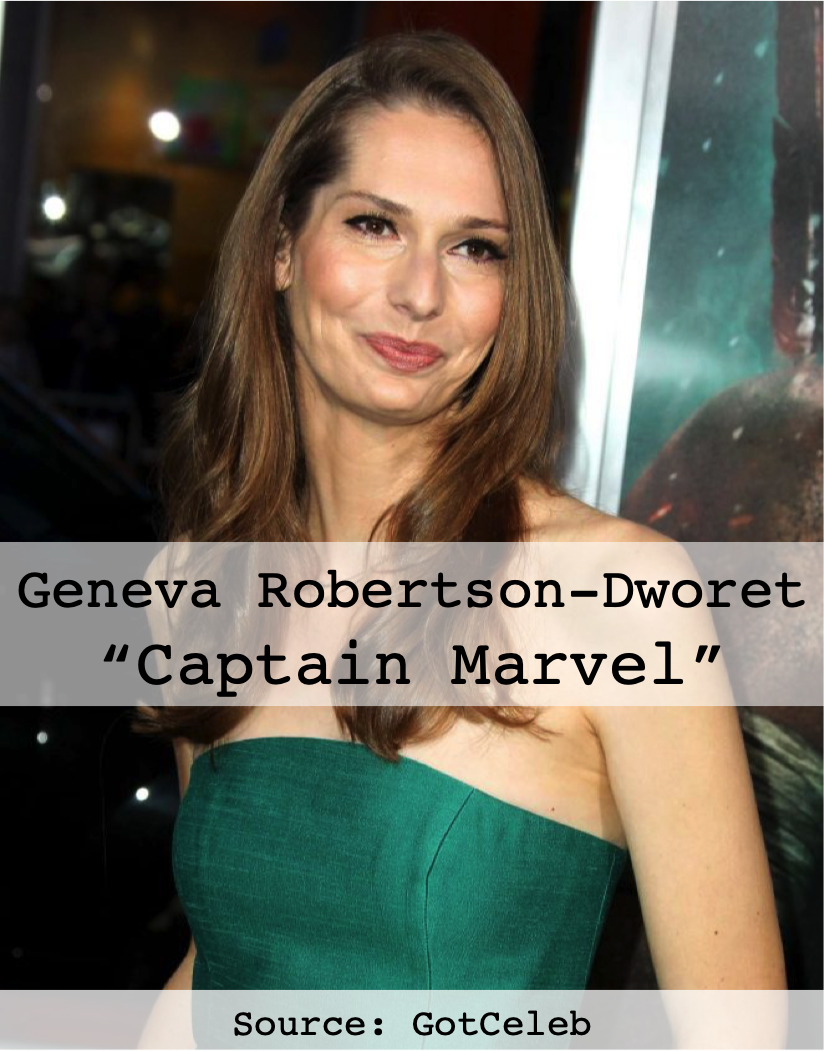

Geneva Robertson-Dworet

"When we talk about increasing representation of women, we tend to focus enormously on female directors. This is obviously important, but we need to remember that women need more representation in every part of the industry."

Robertson-Dworet is one of the screenwriters credited with bringing Marvel's first female superhero to the big screen. She's also helping to forge a community for women within a genre long considered to be made by and for men.

"Captain Marvel" is the first picture from the comic book publisher-turned-juggernaut movie studio not only to star a woman but to be directed by one as well. Despite a firestorm of fanboy backlash, the film has grossed over $1 billion (and counting) worldwide since its release in March.

Just like her protagonist, Robertson-Dworet had her sights on the skies from an early age.

"When I was a kid, I always spent my free time writing," she said by email. "I was always drawn to the higher stakes and larger scope that's inherent to action films."

She would later attend Harvard University and even write for The Harvard Lampoon, the university's illustrious 143-year-old humor publication. But even equipped with an impressive résumé and alma mater, Robertson-Dworet faced resistance when she entered another notorious "boys club": blockbuster screenwriting.

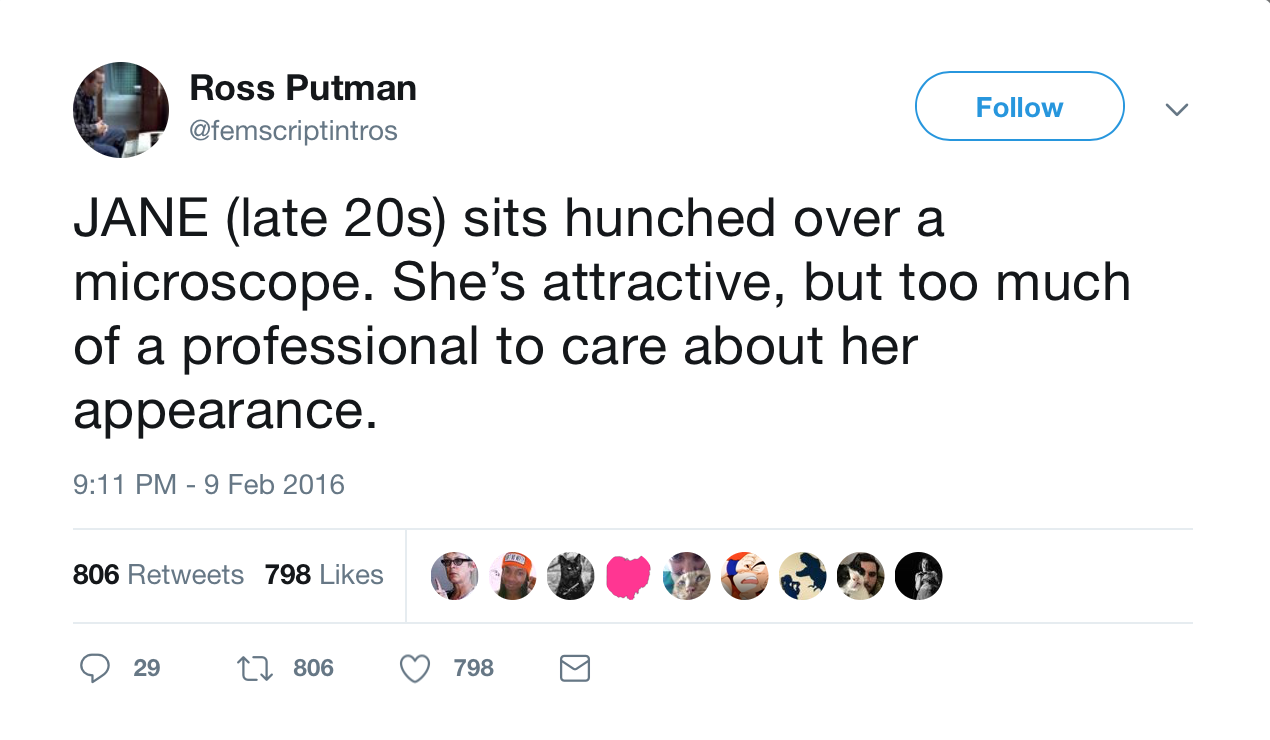

"One of my first pitch meetings was to a male director with an action sci-fi concept,"she said. "I pitched out my action-filled take and then he said he wanted a 'more muscular take.' I took that as code to mean that what he really wanted was a 'more male' writer."

Nevertheless, Robertson-Dworet persisted. She worked in the writers'room of the "Transformers" franchise at Paramount before drafting the story and screenplay for "Tomb Raider"(2018).

"Most of my first jobs came from female executives,"she said. "This is important because when execs hire an inexperienced writer, they're taking a big risk."

It was fitting that Robertson-Dworet would receive her big break (or rather, bigger break) on the rare female-dominated production of "Captain Marvel." She believes that the talent behind the camera helped to give the titular hero a complexity usually reserved for male characters in the superhero genre.

"I think Anna Boden, our female director, was integral in ensuring this kind of nuance existed in Carol's character," Robertson-Dworet said. "Moments of humility help make Carol stronger, and allow her to grow."

Still, at least some credit in making the character more than a perfect hairdo and spandex outfit was due to the writing.

"I think it was important to us to explore contrasts within Carol," Robertson-Dworet said. "We all wanted to make Carol hyper-confident, but we also wanted to show that her strength and confidence don't prevent her from admitting when she's on the wrong side or has made a mistake."

In 2018, Robertson-Dworet decided that she wanted to honor the female creators who helped jumpstart her career and pay the favor forward. Along with Nicole Perlman (co-screenwriter behind "Guardians of the Galaxy") and Lindsey Beer (writer of the upcoming "Chaos Walking" and "Masters of the Universe" reboot), she established a production company called Known Universe.

"I think Nicole Perlman, Lindsey Beer and I all felt that we could have a greater impact and help foster more female voices if we weren't just working in the industry on a project-by-project basis, which is how studio feature writing operates," Robertson-Dworet said.

With literally billions of eyes watching each installment, the films of the Marvel Cinematic Universe are some of the most-viewed stories in the history of humankind. No pressure.

It's for this reason that Robertson-Dworet believes that the genre possesses a special responsibility to lead the industry in terms of diversity and inclusion.

"We wanted to be producers so we could determine which writers get hired on projects and hopefully amplify more diverse voices who are often overlooked in the action genre."