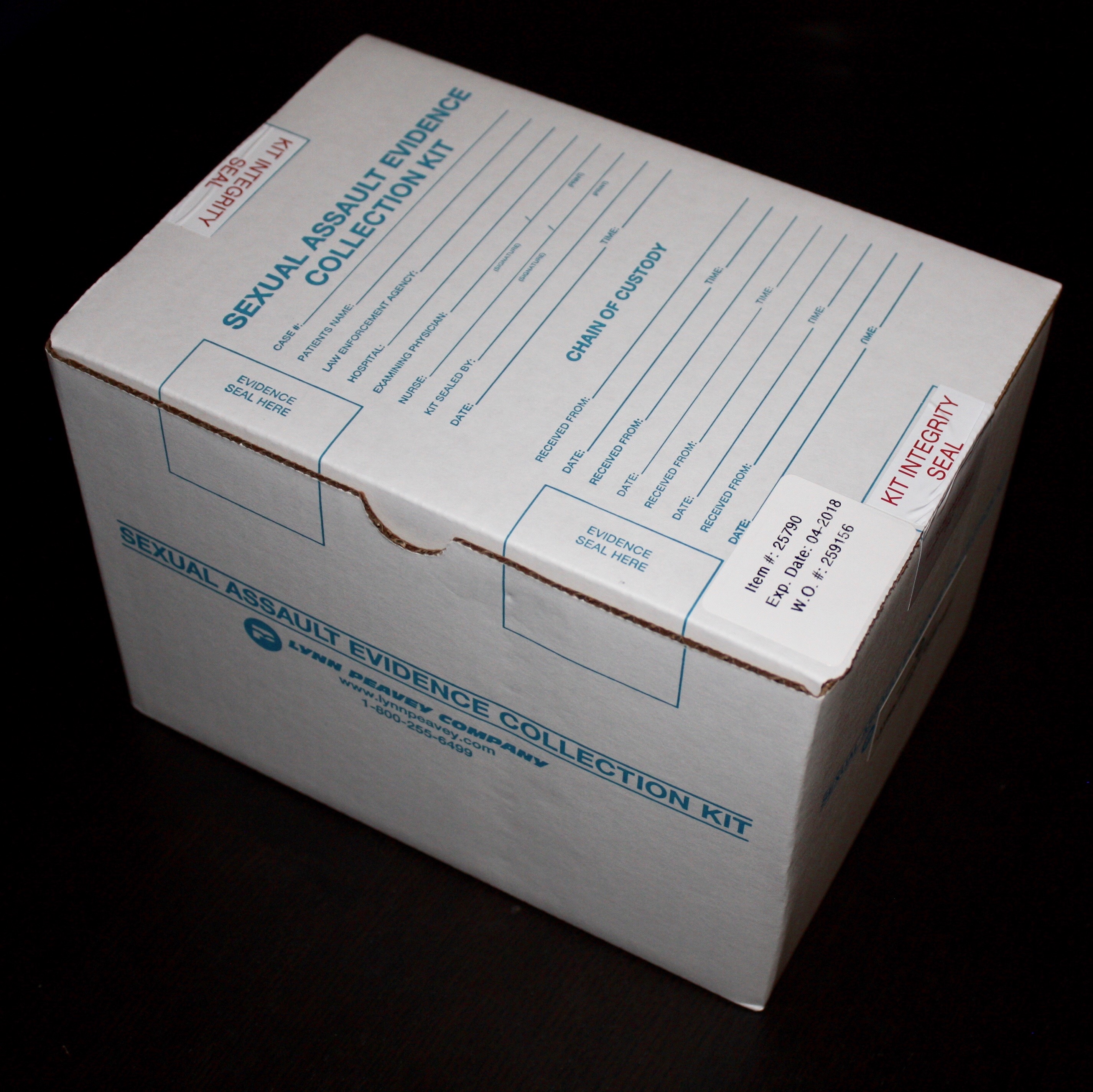

Rows of rape kits await testing. Still from "Testing Justice."

A second trauma

california's rape kit procedures re-vicitmize sexual assault survivors

by Julia Gibson

In May of 2013, Amanda* woke up one morning in a bed that was not her own. She was confused, struggling to think clearly through a raging headache.

“My pants and underwear were off and I was extremely sore down there,” she says. “ My legs hurt like I ran a marathon.” She knew something was wrong.

“I immediately called my sister and told her everything. She just kept saying “you need to go to the hospital,” she says. “I was so confused. How did a night out with friends turn into this? A possible rape?”

I felt like I was being violated all over again.

At her sister’s insistence, Amanda went to the hospital nearest her home. A nurse greeted her and asked what she could help her with.

“I whispered and leaned over the desk to be close to the nurse’s ear and said, ‘I think I was raped last night.’”

The night before, she had been out drinking in downtown Long Beach, an area packed full of alehouses, whiskey bars, and rooftop cocktail lounges. She accepted the offer of a ride home from a guy she knew from her small college classes. She trusted him to get her home safely. Now here she was.

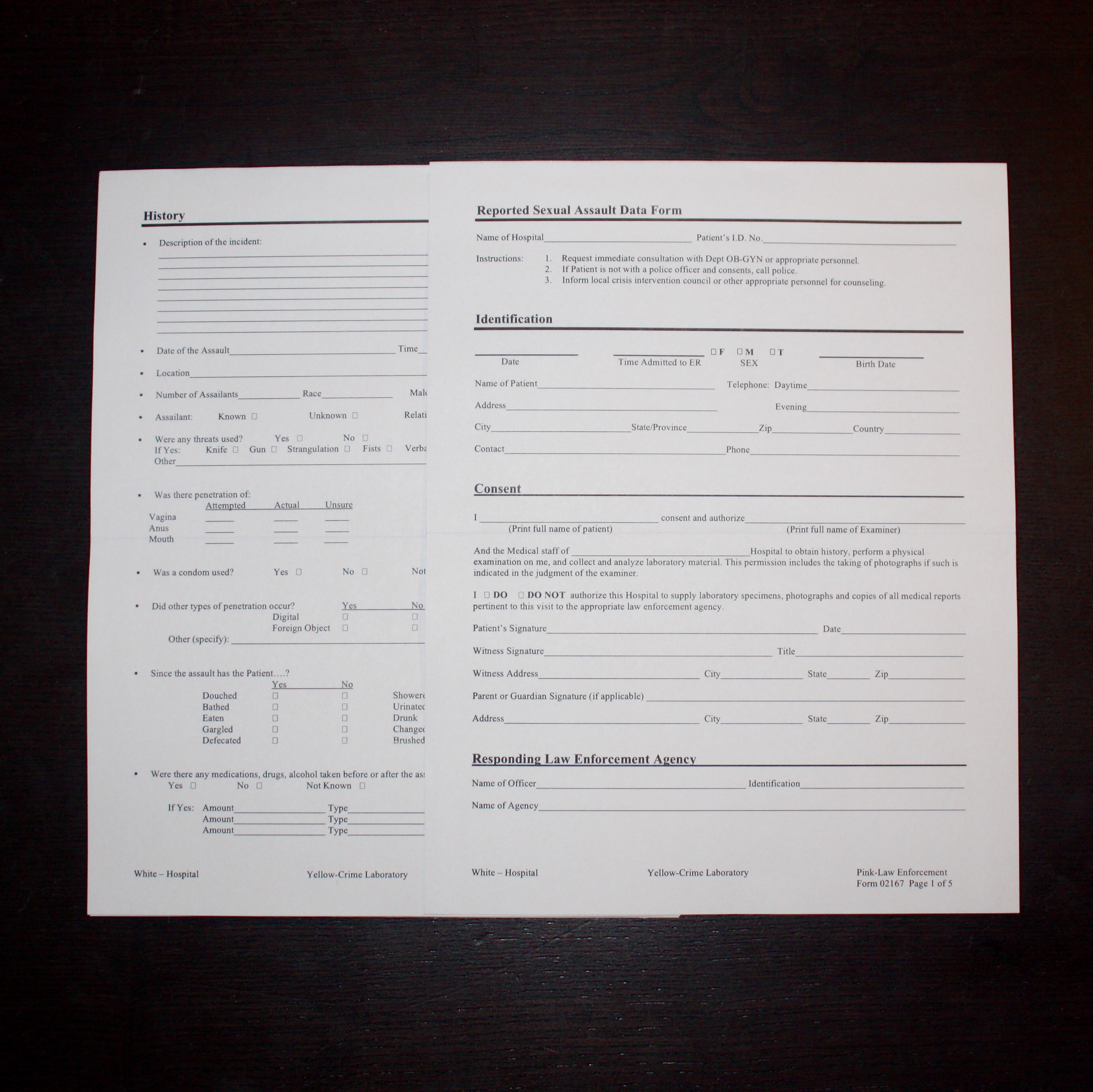

She was told that the hospital could not collect a rape kit, and was directed to a rape crisis center about half an hour away. She was not allowed to leave the hospital until she gave a testimony to the police, who took almost two hours to arrive. She was not allowed to urinate for hours.

“They told me that I could not remove my clothes, that I could not eat, that I could not drink, that I could not go to the bathroom in any form. Anything that could distort evidence before the tests they had to run,” she says. “I just wanted to shower everything away and crawl back into bed.”

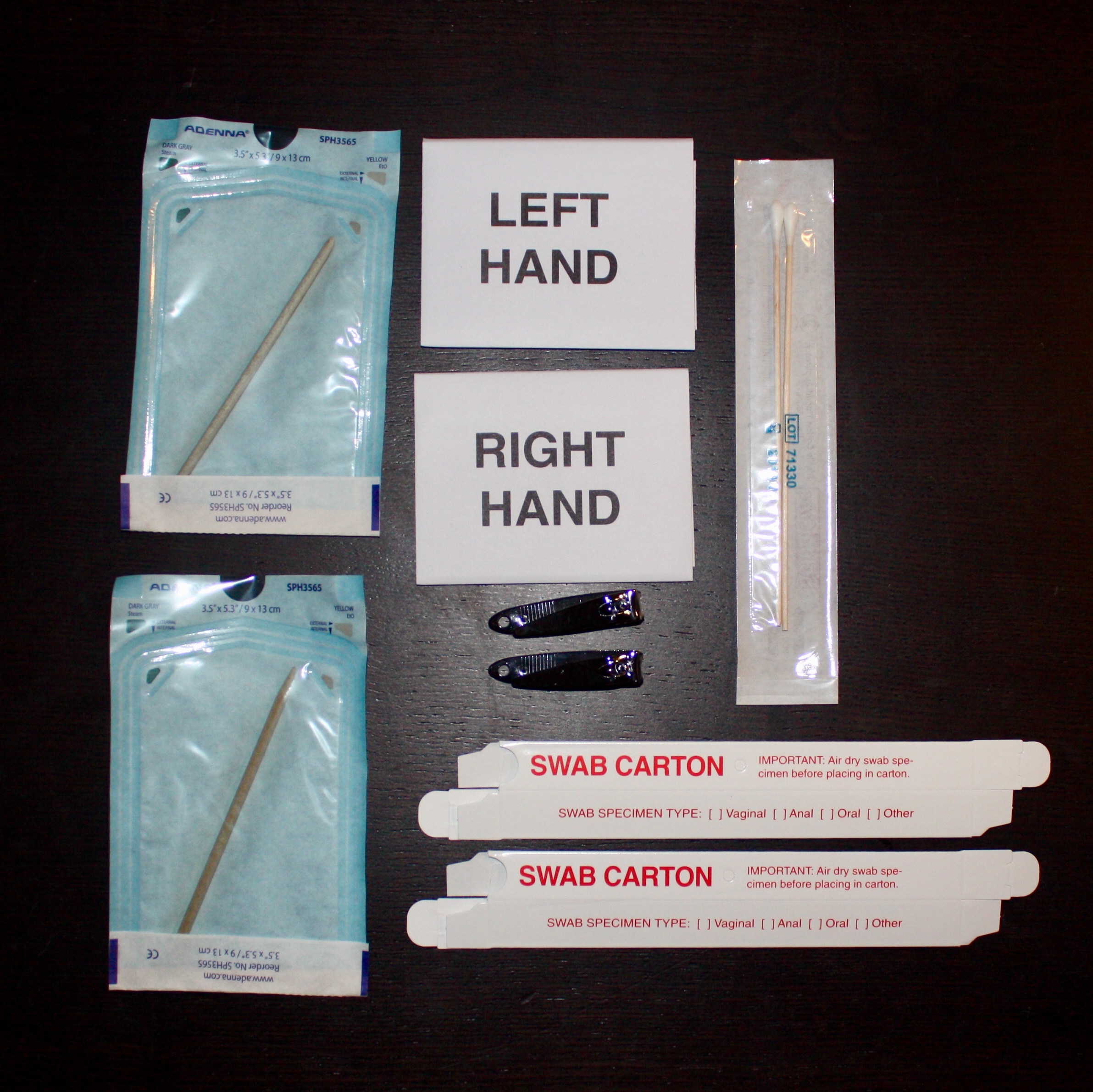

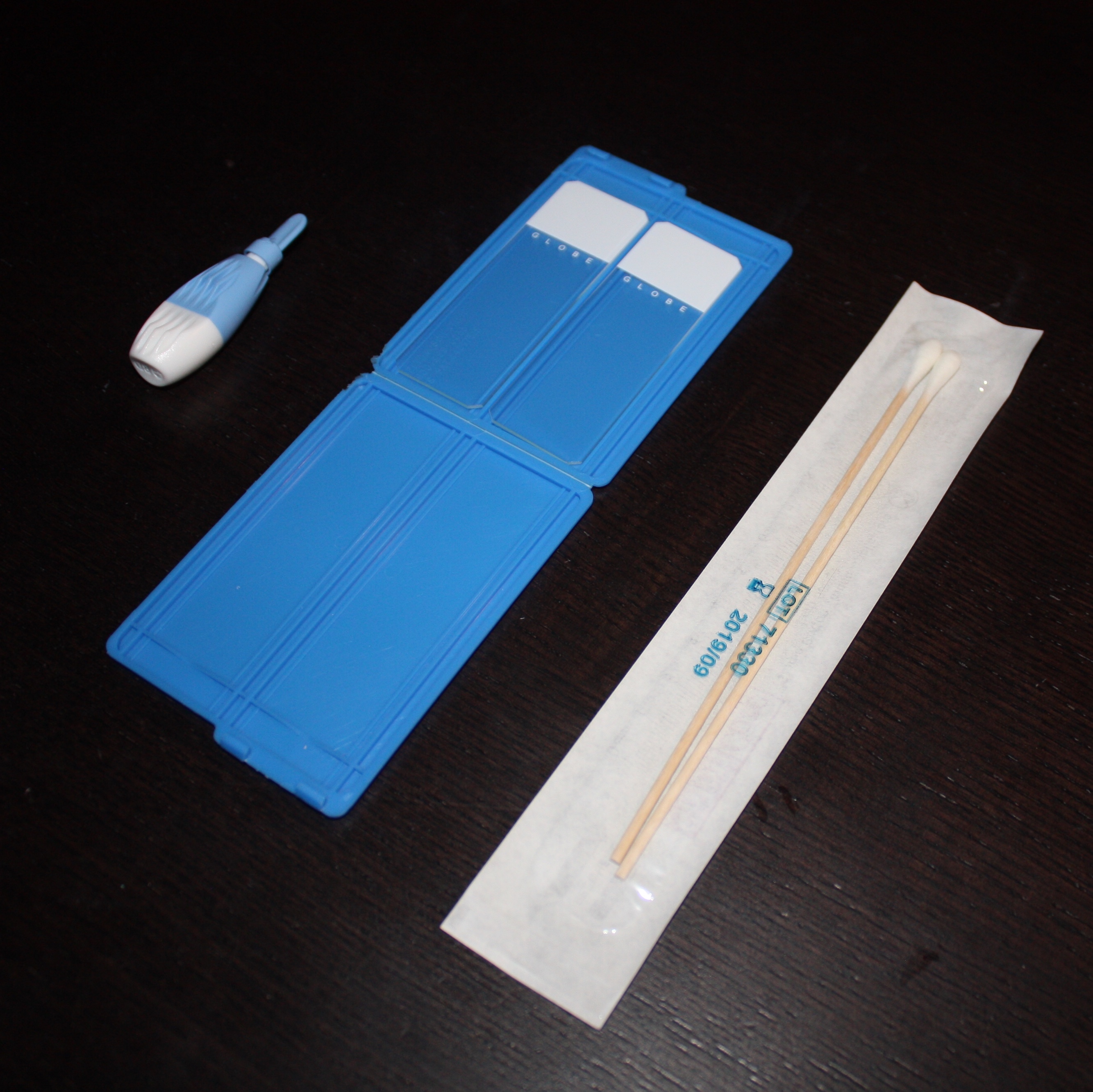

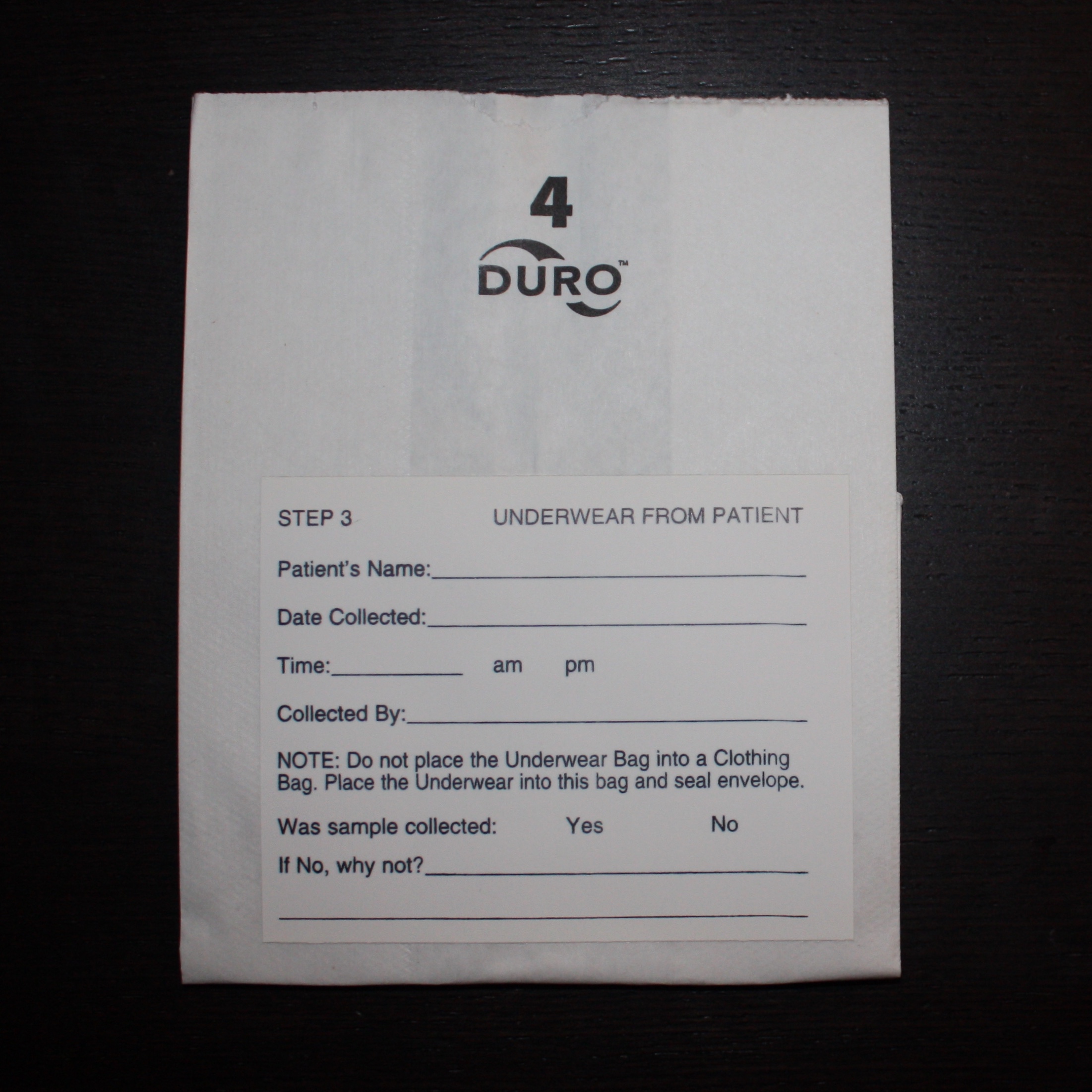

But she couldn’t. Once she arrived at the rape crisis center, Amanda spent hours being examined, every inch of her body documented.

“They took pictures of my legs, my knees, my ankles, my feet, my toes, my nails. They spread my legs and took pictures of my vagina from all angles… I felt like I was being violated all over again,” she says.

A nurse searched her for any possible pieces of evidence. “She swabbed me in every crevice, every hole. It hurt. Everything down there was still fresh and painful,” she says. The nurse informed her that she had “definite tear and bleeding and bruising.”

The physically invasive procedure did nothing but upset Amanda.

“I hated that I had to experience twice the trauma. I hated how the police were there because it did not make me feel any more safe than I was already feeling. I hated how I felt more violated that day than I did the night before,” she says.

“I was so angry that I had spent my entire day being examined by a forensic team like a dead corpse.”

Read more...

Amanda encountered all the organizations that are typically involved in rape kit collection: hospitals, law enforcement, and rape crisis centers. Yet, she felt protected by no one. Her experience is unfortunately not unique.

In 2016, the number of rapes known to law enforcement in the state of California totaled 13,702. In the city of Los Angeles, the total was 2,343. And these are just reported cases. According to the Rape, Abuse, & Incest National Network (RAINN), only 310 rapes out of 1000 are reported. Out of those reports, only 57 arrests are made, and only 6 rapists will spend any time behind bars.

The number of convictions is slim due in part to the large amount of untested sexual assault examination evidence, often called the rape kit backlog. End the Backlog, a non-profit organization dedicated to educating and empowering survivors, estimates that the state of California currently has approximately 13,615 untested rape kits.

According to RAINN, 7 out of 10 sexual assault victims know the person that raped them. It is more likely that their rapist is an acquaintance, spouse, significant other, friend, or family member than a stranger.

An issue that often arises is whether or not to test the DNA collected in an exam for an assault where the victim knew their assailant. Many police departments opt not to send those for testing. Some, like Emily Austin, Director of Advocacy Services at the California Coalition Against Sexual Assault, say that "evidence collection isn't needed in those cases."

If a sexual assault exam doesn't make it from the hands of law enforcement to a laboratory tor testing, or remains untested in the lab, this significantly stunts any case a victim has against a perpetrator, no matter their relation to them.

DNA, in these cases, isn't necessarily needed to identify an unknown perpetrator. However, it can still prove useful, both for the victim's case and the community at large.

“Rape is the only crime where it makes a difference whether the perpetrator is known to the victim or not,” says Natasha Alexenko, founder of Natasha’s Justice Project and a sexual assault survivor. “Not testing a case presupposes that it’s going to be a he-said she-said case."

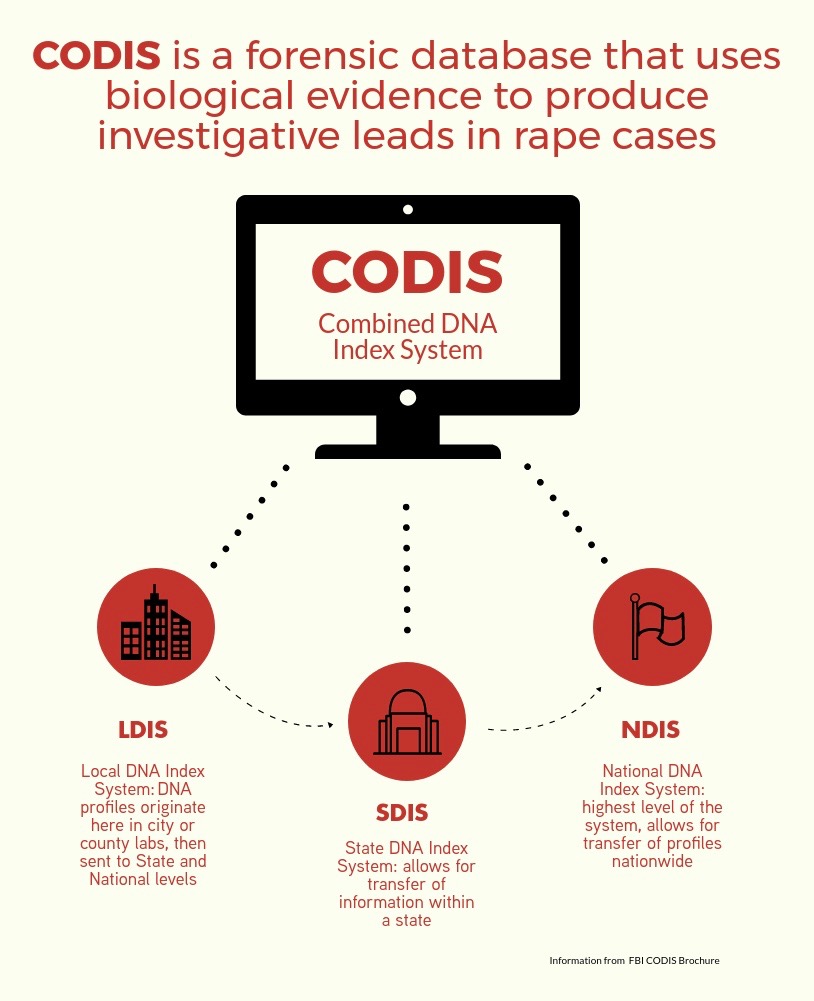

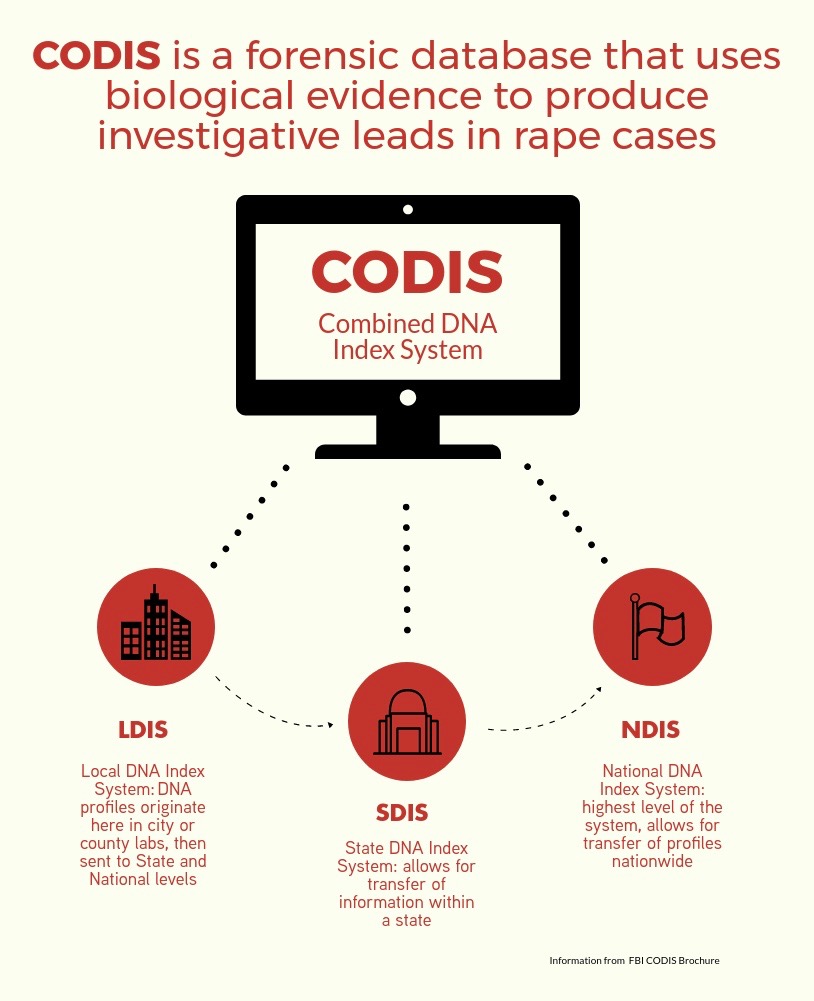

Collecting strong DNA evidence of the assault strengthens a victim's case. Alexenko’s rapist, who she did not know, was picked up on charges of assaulting an officer over a decade after the rape, and was only tied to her assault through the DNA evidence she provided. She points to the fact that many rapists already have criminal histories, so having their DNA in the Combined DNA Index System (CODIS), can be useful.

“If you load that DNA into CODIS, oftentimes you find that it hits to other assaults, and sometimes other crimes in general,” she says.

Sgt. Robert Gallagher of the Long Beach Police Department Sex Crimes Detail says that their special victims section makes sure to test all evidence for sexual assault cases in which the victim knows their assailant, “unless the victim declines a sexual assault exam.”

In addition to the potential crime-fighting benefits, the validation that testing a kit can bring a sexual assault victim, especially after the difficulty of a physically invasive, emotionally taxing, 2-4 hour long testing process is invaluable.

“To survivors in both cases, whether it’s a stranger or someone they know, it certainly feels the same. It’s certainly just as upsetting and harmful and devastating, so why law enforcement decides that one kit gets processed and one doesn’t make sense,” Alexenko says. “The brain doesn't differentiate between being raped by a stranger or by someone you know. It still reacts as though your body is in danger of dying, regardless.”

“It makes all the world of difference to a survivor because you're showing you believe them when you test the rape kit,” says Alexenko.

End the Backlog cites a lack of policies in place for rape kit testing, negative beliefs and stereotyping about sexual assault victims, and lack of personnel and money as reasons why a kit would get left behind.

Alexenko sees these as symptoms of a larger societal problem. “There’s not a focus on these sorts of crimes, which take a lot more work, which take a lot more resources.” She says that bias against rape victims is an issue that can’t be ignored.

“Some of us are judged and that’s why we have these scenarios where we have tens of thousands of rape kits collecting dust. It needs to stop. This is causing a public safety hazard," she says.

Two assembly bills that would amend California’s policies on rape reporting currently sit on Governor Jerry Brown’s desk, waiting to be signed. AB 41 and AB 1312 aim to reduce the number of untested rape kits in California as well as expand protections for sexual assault victims.

One of these bills, AB 41, would require that all law enforcement agencies report information regarding rape kit evidence to the Department of Justice within 120 days of collection. They would be required to report whether biological evidence samples were submitted to a DNA laboratory for analysis and if a DNA profile was generated. The bill would additionally require that labs provide a reason for not testing a sample every 120 days the sample remains untested.

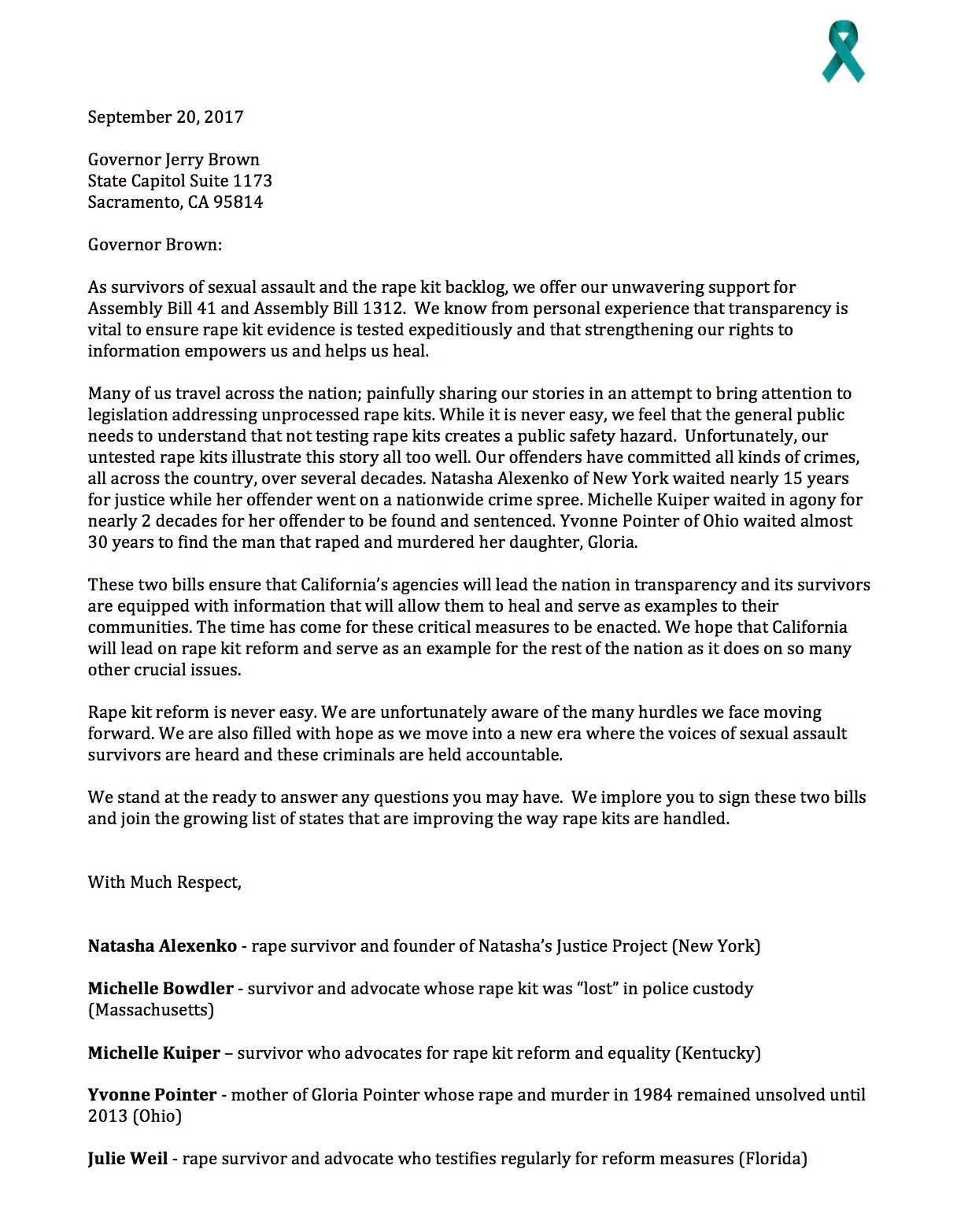

Sexual assault survivors and advocates, including Natasha Alexenko, sent a letter urging Governor Jerry Brown to signs AB 41 and AB 1312.

Sexual assault survivors and advocates, including Natasha Alexenko, sent a letter urging Governor Jerry Brown to signs AB 41 and AB 1312.

Emily Austin says that there are problems that need to be addressed even before the testing stage.

“Rape kits need to be collected in what we would frame as a trauma informed manner, which means that that they are aware of trauma, and actively resist re-traumatization in their process and response,” says Austin. “It’s really traumatizing. It’s very physical, it’s very medical,” she says. “The whole process itself creates a very violent situation for survivors. This new legislation is trying to improve that, by having requirements in place trying to mitigate that and lessen that, but it’s hard. It is yet another trauma.”

AB 1312 is attempting to codify a better way of treating victims. The bill calls for increased protections for sexual assault victims, which includes explicitly notifying them of their rights before, during, and after the kit collection process, ensuring they have an advocate present for support, and readily providing them with information about their case.

Austin says that this approach can help ease the pain of an already difficult situation. “A lot of it centers around rape advocacy skills like listening, being responsive, and providing choices, explaining and exploring choices with a person. That is really powerful and empowering,” she says.

Los Angeles has historically had a poor track record when it comes to handling rape kits. In 2009, Human Rights Watch stated in a report that Los Angeles County had the largest known rape kit backlog in the United States, with 12,000 rape kits sitting untested in police storage facilities. The city of Los Angeles had 6,132 of those kits.

By 2011, the county had gathered enough money and support to successfully test all backlogged kits. Of the DNA samples collected from those cases, 753 of them yielded hits in CODIS.

Sergeant Gallagher says that Long Beach did their part. “From 2008 through 2011, the Long Beach Police Department tested all previously untested sexual assault kits and eliminated any backlog.”

It seems that the Los Angeles backlog is nowhere near where it used to be. However, the backlog is not a thing of the past. A 2014 California State Auditor’s report on sexual assault evidence kits stated that “questions remain as to whether the LAPD will be able to avoid a subsequent backlog, especially in light of budgetary woes in Los Angeles and throughout the state of California.”

In 2011, Governor Jerry Brown vetoed AB 322, a bill that placed similar time limits on rape kit testing as AB 41. Because of this, advocates are nervous for the bills that are currently on his desk.

“If you’re looking at it from the outside, you might be like, why are you still fighting for it? It’s great, it’s on the governor's desk. But we've seen this happen before in California. We want to do everything we can to make sure they pass, because it’s just nonsense to not have it pass” says Alexenko.

Read more...

Those who are fighting for the passage of these bills are pointing to the success of other areas of the country that have implemented similar legislation.

“The examples from jurisdictions such as Manhattan, New York, and Wayne County, Michigan, show that investigative outcomes of certain cases can benefit from expanded analysis of large numbers of previously unanalyzed kits,” according to the 2014 Auditor’s report.

Those benefits included some hard results in Los Angeles. According to the report, “The data the department provided show that, as of June 2014, its analysis of 6,132 previously untested sexual assault evidence kits has resulted in five convictions, three arrests, and three arrest warrants.”

Alexenko, who testified in support of New York legislation, agrees that these benefits are clear. “Everyone in law enforcement that I speak to says it helps them. It’s a great investigative tool. Even if you don’t care about survivors and what we go through, it keeps criminals off the streets,” she says.

At this time, law enforcement agencies in California are not required to report the number of untested rape kits. Sergeant Gallagher says that in his division, which deals with about 100 rape kits annually, “most sexual assault kits are submitted.” The victim has the option to hold off on testing for any reason, and in that case, “exams are held for two years."

“If the victim changes their mind and wants to continue with an investigation, we forward the kit for analysis.” Gallagher says.

After a long morning of testing, Amanda chose not to officially report her rape and press charges, for fear of public judgement or retaliation. She would have to see her assailant in classes, on campus, around town. She now lives in a different state, in a new city without the painful memories. She wants to forget what happened, but can’t.

“Eventually the memory was just burned into my mind as a terrible night. It was something I didn’t want to remember…yet every time I read a book, or watched a movie, or heard a remark on the street that mentioned rape, I was reminded of that night and that following day,” she says.

* name has been changed to preserve anonymity.