PRESERVING TU’UN SAVI,

THE LANGUAGE OF THE RAIN

AN EFFORT OF A MEXICAN INDIGENOUS MIGRANT COMMUNITY IN CALIFORNIA

Rapping to Preserve Tu’un Savi

Una Isu is a trilingual rapper who produces content in Spanish, English and Mixteco. His lyrics tackle issues about identity, immigration and indigenous rights. If the video does not play, please click here.

THE SURVIVAL OF AN ANCIENT MEXICAN LANGUAGE

On the ground, there is an altar covered with colorful flowers. Some are yellow, others are orange and purple. An image of la Virgen de Guadalupe, which is a symbol of faith for Mexicans, rests on the side of the altar. There are a couple of indigenous elements decorating the scene such as stone writings and sculptures.

With a microphone in his hand, Miguel Villegas walks up the stage in the middle of Mariachi Plaza in Boyle Heights. Villegas introduces himself as Una Isu, which means Ocho Venado or Eight Deer. The music starts playing and the crowds are cheering. Una Isu takes a deep breath and begins his performance. Una Isu is a trilingual rapper.

With pride, Una Isu wrote Mixteco es un lenguaje, which translates to “Mixteco is a language.” Una Isu raps in English, Spanish and Tu’un Savi, which is also known as Mixteco. Tu’un Savi is an ancient Mexican language and its presence has defied colonialism, immigration and discrimination.

In his song, Una Isu raps:

Naa keiin luluu tuun tavi, tanaa intantoso ntoo

(I’m going to speak some Mixteco, so you don’t forget it) [...]

A native from Nuu yuu kuu (on top of the hill) I will always be Mixteco hasta la muerte (until I die).

A song like Mixteco es un lenguaje is part of a broader movement with a specific goal: keeping Tu’un Savi alive and empowering those who still speak the language in Mexico and the U.S.

Una Isu says his music is able to bridge communities both young and old because he combines a musical genre that is mostly heard by millennials with an ancient language that is mostly spoken by elders. “I have broken the stereotype that rap is always negative. It can be productive, it can be a form of resistance,” Una Isu explained.

Mexico is one of the most diverse countries linguistically and ethnically. To this day, there are 68 native languages spoken in the country; however, many of them are at risk of becoming endangered.

According to the Mexican National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI), only 6.5 percent of the Mexican population spoke an indigenous language in 2015. Mixteco is the fourth–most–spoken native language in Mexico, but it only represents 7 percent of the total number of native speakers. That same report shows that most indigenous communities tend to migrate to other places.

Based off codexes, experts say the first records of Mixtec dynasties date back to the 10th century. However, archaeologists say there were farming settlements in the area since 1500 BCE.

Mixtecs identify as Ñuu Savi, which translates as “the people of the rain,” and they speak Tu’un Savi, “the language of the rain.” The language is part of the Otomanguean group of Mesoamerican languages. Tu’un Savi is a tonal language, and it tends to be very descriptive, which is why trying to do a literal translation from an ancient language like Tu’un Savi to English or Spanish is difficult.

Most of them are from Oaxaca, part of Puebla and Guerrero. The Mixteca region is divided in three areas: the high, the low and the coast. Because of how diverse the Mixteca is geographically, there are estimates of over 30 variations of Tu’un Savi.

Due to migration patterns throughout history, there is also a significant Ñuu Savi presence in Northern Mexico.

While Mixtec/Mixteco have been the terms used to refer to the Ñuu Savi, this is not the name they give themselves. The Nahuas, another Mexican indigenous community, named the region where Mixtecs lived Mixtlan, which means “the land of the clouds” or Mixtecapan, “the country of the Mixtecs.”

Once the Spanish conquered Mexico in the 16th century, the term “Mixteca” was used to refer to the geographic area, and its people were known as Mixtecos.

Silvia Ventura is a professor at California State University Channel Islands in Camarillo, California, where she teaches Mixteco 101. Ventura said it is important to discuss the history and culture that represents the Mixtec community.

In the ’90s, la Real Academia Mixteca was founded with the goal of preserving the Tu’un Savi language. They created an alphabet, which borrows letters from the Spanish alphabet. Another of their goals is to empower this community, which has often suffered discrimination in both Mexico and the U.S.

“La Academia Mixteca has been very much forward towards: we need to be more proactive and say it's Tu’un Savi because it creates this idea of empowerment and being able to say, ‘This is a legit language, and it's something that deserves to be called by owning rather than a name that was given to it,’” Ventura said.

Gaspar Rivera-Salgado is a professor at the University of California, Los Angeles and longtime researcher of indigenous Mexican communities. In his book Indigenous Mexican Migrants in the United States, Rivera-Salgado explains a history of migration the Mixtecs have followed since the 1910 Mexican revolution.

“Oaxaca is one of the poorest states in Mexico, and the majority of the population survives from farming jobs,” Rivera-Salgado said. “[Mixtecs] have a long history of migration towards the United States, but their migration starts within Mexico.”

The first migrations from the Mixteca region were toward the states of Veracruz and Baja California. This movement was promoted by enganchadores, or labor contractors, who recruited Mixtecs promising good jobs, good wages and good living conditions.

The Bracero Program, a U.S. initiative that brought guest farm labor from Mexico between 1942 and 1964, caused an influx of migrants to leave the Mixteca.

Mixtecs have been farmers for centuries, so they have used those specific skills to find agricultural jobs outside of the Mixteca. This is what Rivera-Salgado calls specialized migrations, which has led to thousands of families settling in areas where agriculture is part of the main economy.

Some Mixtecs have stayed in Northern Mexico; others made a leap of faith and traveled to California seeking jobs in San Diego County and the San Joaquin Valley. A few have migrated all the way to Canada.

One of those hotspots for Mixtec migrants is Fresno, California.

CHASING THE OAXACALIFORNIA DREAM

“Oaxacalifornia” is a term used to describe the merging of cultures due to migration between the state of Oaxaca in Mexico and the state of California in the U.S. It is a constant fight between adaptation and assimilation.

Una Isu left San Miguel Cuevas–Nùù Yukù, his hometown in Mexico–and came to the U.S. with his siblings and mother when he was 7 years old. Like many Mixtec migrant families, his started working in the fields in Fresno, California.

When asked, why Fresno? Una Isu says there was already a fixed migration pattern.

According to a 2010 study by Indigenous Mexicans in California Agriculture (IFS), many migrants follow a so-called “hometown network,” which is a “social structure that exists among the people from the same village or locality in Mexico.” This helps the newcomers feel a sense of comfort and belonging in this new place where they oftentimes won’t even understand the language.

Una Isu says there is a large group of Mixtecs from his hometown, San Miguel Cuevas, in the area. It was thanks to that social network that his family found a support system and a place to stay.

For many of these migrant families, Mixteco is their native language, so Spanish and English become their second and third languages.

Discrimination and bullying were part of Una Isu’s migrant experience.

“They made fun of us because we couldn’t speak Spanish nor English properly. But it was because we spoke the language [Mixteco],” Una Isu recalled. “I didn’t understand why they did it, but then again, it happens in Mexico.”

He was also bullied because his family members were farmworkers. Una Isu faced identity issues to the point where he felt ashamed of his Mixtec heritage.

“I wanted to hide who I was, hide the language. I focused on improving my English and Spanish. I even felt like Mixteco was a barrier for me to learn English. I stopped speaking the language [Mixteco],” Una Isu recalled. “People would talk to me in Mixteco, and I would respond in Spanish.”

Mixtecs in California have found a way to transform the frustration that once felt like a barrier into a strength.

“This has pushed migrants to create ethnic organizations,” Rivera-Salgado said.

Many of these young migrant Oaxacans have come together since the '90s to found community organizations such as FIOB (Frente Indígena Oaxaqueño Binacional/Oaxacan Indigenous Binational Front), CBDIO (Centro Binacional para el Desarrollo Indígena Oaxaqueño/Binational Center for the Development of Indigenous Oaxacans) and Los Autónomos (The Autonomous), among others.

Volunteers at these organizations will host “know your rights” workshops, teach Tu’un Savi and organize events that celebrate and discuss traditions.

“We now have a generation that has a unique experience of navigating three worlds because they are trilingual,” Rivera-Salgado said. “They build upon their native language, Mixteco, and learn both English and Spanish simultaneously.”

While there seems to be a large number of Mixteco speakers in California, it is hard to know how many there are and even more difficult to identify how many of them are trilingual. IFS estimates that there are about 500,000 Mixteco speakers in both Mexico and the U.S.

Rivera-Salgado said the main problem is not that Mexican immigrants do not assimilate but rather that they assimilate very quickly, so the risk of losing their heritage is high. He said part of the problem is that there is not a support system that promotes multilingual speakers.

The IFS found that “the practice of speaking in the native tongue to children declines as soon as the family gets established in the United States.”

“It appears that a large minority continues the tradition of speaking only in the native language (40%) while the rest (60%) once established in California speak either only Spanish or a mixture of Spanish and the native language to their children.”

One of those migrant families trying to pass along their language and culture is Catalina Mendoza’s. She came to the U.S. almost 20 years ago following the steps of several family members. While Mendoza has been able to pick up on some Spanish words, she prefers to speak Mixteco.

“As for my kids, they don't speak Spanish. It's only until school that they started taking some Spanish classes. They might understand it, but they cannot respond,” Mendoza said.

Mendoza is a stay–at–home mom and her husband is a farmworker. The mother of four speaks only Mixteco at home, so her children have learned the language.

“Well, they don't get confused or get mixed up because they go and speak English in schools,” she said. “Here, we speak to them the language [Mixteco] and they understand it very well.”

In addition to speaking the language at home, she talks to her kids about what life in the Mixteca was like, and she tries to go to cultural events organized by CBDIO and FIOB.

“I would like for them [my kids] to talk about our language, to pass on our language…,” Mendoza said.

Meet Catalina Mendoza

Mendoza is a stay home mom of four living in Fresno. She is from a Mixtec community in Oaxaca, Mexico. Although she has lived in the U.S. for about 20 years, she encourages her kids to speak Mixteco and pass along their culture. If the video does not play, please click here.

PRESERVING TU’UN SAVI IN A HOME AWAY FROM HOME

Rivera-Salgado says that when compared to other indigenous migrants, Mixtecs have a flexible identity because they are able to adapt to the American lifestyle, but they still have emotional and financial ties to their hometowns.

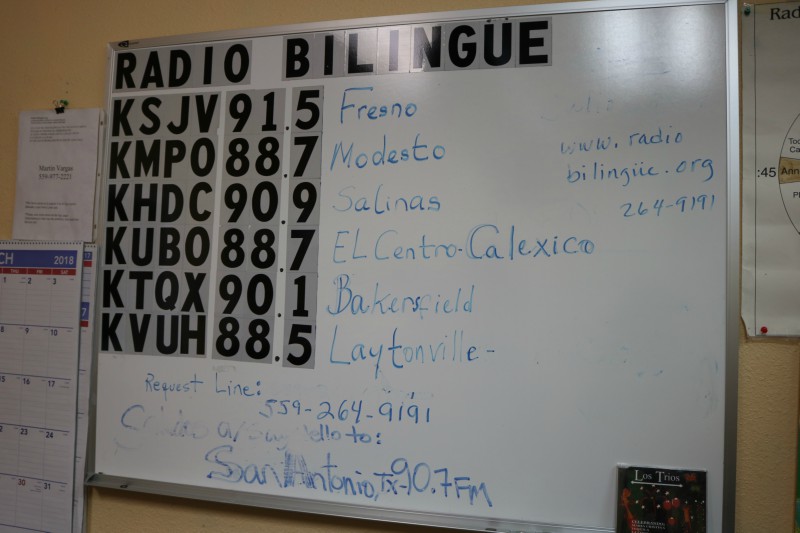

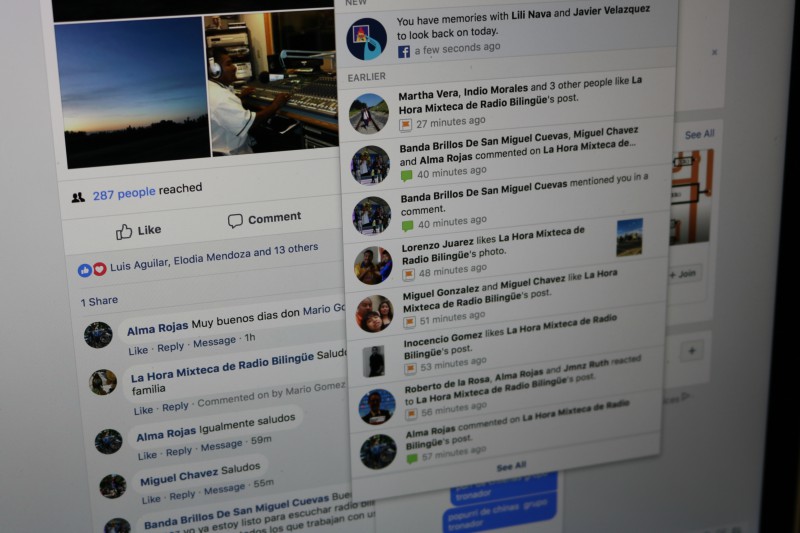

One way Mixtec communities keep in touch is through bilingual radio shows such as La Hora Mixteca, which translates as “The Mixtec Hour.” This four–hour show, which is produced in both Spanish and Mixteco, airs weekly and has been around for over 20 years, thanks to the work of the volunteer hosts.

La Hora Mixteca links to sister stations in Mexico, so it has a constant influx of phone calls where people on both sides of the border get to send some greetings to their loved ones. Most of the time the show has a guest come in to chat, and they play traditional music from Oaxaca and Guerrero.

Mario Gomez is volunteer host who also works at a ranch where he handles heavy machinery. He says it is a pleasure to work at La Hora Mixteca in his spare time because he has found a home in this show.

“It’s a good way to remember where we come from and where we are from,” Gomez said.

Host Natalia Bautista is an interpreter at a clinic in Santa Maria, California, and comes to Fresno every other Sunday to volunteer her time on the show.

“It’s important to hear our voice in our own language, to listen to our traditional music that we bring with us as immigrants. It’s our way of staying connected with our Oaxacan brothers,” Bautista said.

In an effort to pass Tu’un Savi along, Una Isu has led workshops where he has taught the language within his community in Fresno.

“If I would’ve seen more Mixteco speakers in the media, professors or artists. I would’ve valued my culture more. Seeing more people like me would’ve helped,” Una Isu said.

Professor Silvia Ventura has collaborated with Una Isu and fellow scholars who have built academic plans to teach Mixteco. Ventura adapted the Channel Islands syllabus from San Diego State University, one of the pioneers in teaching the language at the college level.

For many of Ventura’s students, this is the first time they have ever heard Tu’un Savi. There are a couple who are native speakers or have heard their parents or grandparents speak it at home.

Others, Ventura said, “have heard of it just because they're in Oxnard in Ventura County. There's a big presence of the Mixteco community.”

MEET STUDENTS TAKING MIXTECO 101

Xochitl Ordaz, Caitlin Rivas and Gabriela Lopez (from left to right) are all students at CSU Channel Islands. Listen to them introduce themselves in Tu’un Savi and explain why they are taking this course.

“It is a real challenge for linguistic minorities to keep their language if they don’t have the support of public policies and educational systems,” Rivera-Salgado said. “There is no investment in Mexico nor in the U.S., so that’s why it is so important to move forward with community efforts.”

One of those community efforts is through Una Isu’s work as a musician. He raps about immigration, culture and colonialism. Regarding the latter, “it is for that reason that we are fighting to keep our culture. We’ve had a lot taken away,” Una Isu said.

Una Isu thanks his Boyle Heights audience, returns the microphone and walks down the stage. He is embraced by some of his friends, fans and colleagues. He holds a side bag with a couple of his CDs and as he makes his way through the crowds, Una Isu tries to sell some of them.

He carries a smile on his face, but he knows his journey doesn’t end here. He hopes to collaborate with fellow artists who rap in native languages, to return to his hometown to produce content and to continue to empower his Mixtec community.

“[Mixteco] has survived so much. If it dies, part of our history dies with it,” Una Isu said. “It’s the way we communicate with our world, our Ñuu Savi world, the people of the rain.”