Cameras are clicking, and nervous anticipation fills the room. Wayne Gretzky, fresh faced and emotional, dabs his eyes with a tissue. He takes a sip of water and tries to spit out the words, but his sobs won't allow him to. "I promised Mess I wouldn't do this," he says, referring to his teammate Mark Messier. "But um, as I said, there comes a time when…," Gretzky says, trailing off.

Having just finished his ninth National Hockey League season, coming off his team's fourth Stanley Cup championship, "The Great One" stood up from his chair, too choked up to continue.

That news conference, where it was announced that Gretzky would be traded from the Edmonton Oilers to the Los Angeles Kings, will mark its 30-year anniversary in August.

It was, and still is, one of the biggest trades in the history of professional sports. The anticipation from the beginning was huge.

"We got Gretzky," one Los Angeles Times columnist wrote. "Eat your hearts out, world." "Wayne was the catalyst in Edmonton," one NHL executive told the Times. "He can serve the same purpose down there. I think it's a tremendous deal for Los Angeles."

Although Gretzky's nearly eight seasons with the Kings did not result in a Stanley Cup title, his presence in Los Angeles would change the landscape for good. Players, coaches, executives and fans attribute the growth of ice hockey in California, especially Southern California, to the arrival of Gretzky on Aug. 9, 1988.

USA Hockey, the national governing body for amateur play, did not collect participation records as far back as 1988. However, unitedstatesofhockey.com did collect the numbers from USA Hockey starting in 1990-91, Gretzky's third year in LA.

In 1990-91, USA Hockey reported 4,830 players registered in California. Two years later, the number stood at 9,316 and by 1995-96, the year the Kings traded Gretzky, the number reached 15,537 players.

It has been 22 years since Gretzky last donned a Kings jersey. Yet the growth of ice hockey in California has continued. USA Hockey has shattered participation records every year in California since 2010-11, reaching 29,849 registered players last year.

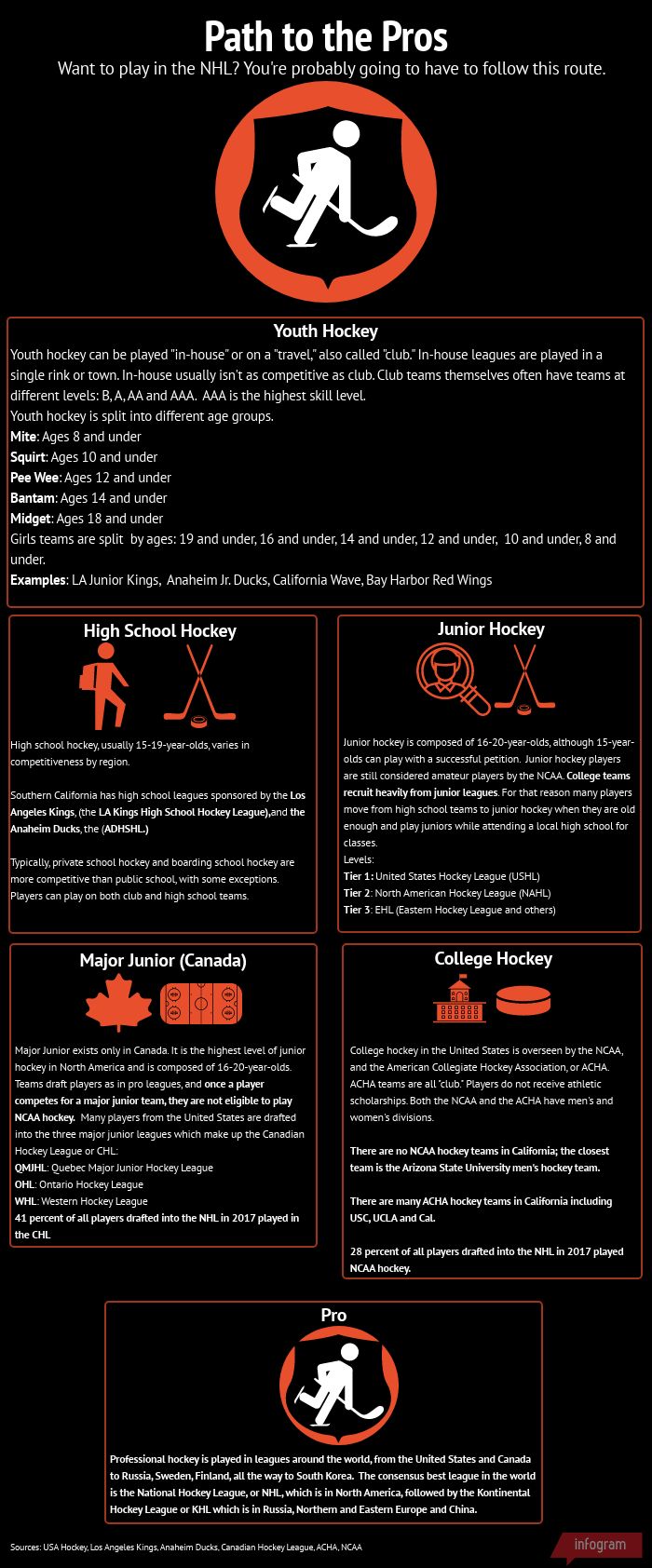

The growth appears to be happening at all levels, for boys and girls, youth to high school and beyond.

Daryl Evans, who scored the game-winning goal in "The Miracle on Manchester" (more on that later), began his NHL career with the Kings in 1981 and has been involved in promoting hockey in Southern California since he arrived. He now works as a radio color commentator for Kings broadcasts.

Evans has witnessed a snowball effect in the growth of hockey. More options to play in Southern California have kept many skilled players, who in years past would have been forced to leave the state to find better competition, close to home. This boost in participation has fueled more visibility, which then works to attract more players.

"It's encouraging more kids to hang around," Evans said, citing the advent of youth leagues and high school teams, including a program funded by the Kings. "Because of the programs that we now have locally, throughout California, those kids are staying here. Because of that, now all of a sudden, their peers are around them, and they become mentors for the rest of the school and the young kids coming up."

Girls' participation has the potential to expand significantly in the next few years because of the recent success of the U.S. women's national team, culminating in its gold medal win at the 2018 Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang, South Korea. Cayla Barnes, a defenseman on the team, hails from Southern California.

Emma Tani, hockey development coordinator for the Kings, credits the role the U.S. women's team plays as ambassadors for the sport.

"Seeing how much of an impact the Olympics had is really exciting, especially for girls in Southern California who have these idols now to look up to," said Tani, who played boys' and girls' hockey growing up in Orange County. "It's really exciting for the sport."

Relatively new high school hockey leagues have seen remarkable growth, already drawing hundreds of players. The Kings and their NHL rivals the Anaheim Ducks have started high school leagues. The two franchises seek to use the programs to boost interest in the sport and add to their fan bases.

Joey Cianfrani is a junior playing on the Newport-Mesa Ice Kings, a team consisting of players from multiple Orange County high schools. He was chosen to represent his team in the Anaheim Ducks High School Hockey League junior varsity all-star game at the Honda Center in Anaheim.

"It's pretty cool," he said. "Not a lot of people really play hockey. So when my name comes over the loudspeaker, I get to brag and tell all my friends I played in the Honda Center."

Some would argue that California is already "hockeytown" as judged by the skill of the state's best players. Jay Trotta, who started playing in Southern California in 1977, now coaches the El Segundo Strikers of the Los Angeles Kings High School Hockey League. He believes that California is on par with other states.

"We have a very high skill level, and there is a very, very committed group of players that put a lot of time into their game," Trotta said. "It's become much more competitive, and if you are from this area nowadays, people take you serious around the country. You're not like a novelty anymore like you used to be."

Thanks to Gretzky and help from professional franchises, hockey has defied many of the obstacles that made it an obscure sport in Southern California. Unfortunately, barriers still remain.

California still trails the five biggest hockey-playing states in the nation as measured by USA Hockey membership: Michigan, Minnesota, Massachusetts, Illinois and New York. Southern California specifically faces two major interrelated obstacles: climate and cost.

It's expensive to keep a rink cold in a desert, so operators charge more for ice time to cover those costs and make a profit.

In addition, even though hockey is not as popular as some other sports, Southern California still has a large number of people who want ice time for other events like figure skating. That high demand combined with limited ice supply drives up the price of renting the ice.

Sgt. Chris Cognac of the Hawthorne Police Department is the founder of the Hawthorne Force program, which gives young boys whose families can't afford hockey the opportunity to play. He explains why potential entrepreneurs chose not to build new ice arenas.

"When you have land value, ice rinks don't generate the amount of money that retail stores have in LA or condos," Cognac said.

Limited ice availability translates to higher per hour rental fees for customers. "They have to pay a lot of money," Cognac said. "The average is about $450 an hour. That's pretty significant."

California's climate plays another role: Hockey faces stiff competition from sports that can be played outdoors, year-round and practically anywhere, whether in an empty parking lot or a park or a school playing field, and that do not require expensive equipment. Soccer, baseball and basketball, which are all more popular than hockey, can be organized and played relatively easily and cheaply. Football, which requires expensive pads and helmets when tackling is involved, can be played as touch or flag football at a much lower cost.

Even street hockey requires sticks, goals and a ball. It's no surprise that kids and adults do not consider hockey their first choice when picking up a new sport.

As proponents for hockey work out the answers to make it easier to access, they are building on a history that started in California more than 100 years ago.

First Period

Fresh Ice

The Los Angeles Athletic Club and the University Club contested the first ice hockey game in Los Angeles at the Ice Palace on Feb. 1, 1917. Warde Fowler covered the game for the LA Times.

In his story, headlined "Ice Hockey Introduced to Enthusiastic Fans," Fowler wrote, "No one was killed outright." The game he described sounded similar to modern hockey. It was just as exciting and confounding to new fans: "When a player can't think of anything else to do, he swats the bean toward the goal keeper with all his might. If this man is lucky he gets out of the way. If he isn't they carry him over to one side of the rink, place him gently on his back and tell him to keep cool till the undertaker arrives."

Since then, Southern California has had a long history with hockey.

If you've ever seen a game, you might have heard the name Zamboni.

Much like Kleenex, Xerox and Jell-O, Zamboni is actually a brand which has become synonymous for the machine that cleans ice in skating rinks. It was invented by Frank Zamboni in Paramount, California. The Zamboni was patented in 1953 and has been cleaning ice in rinks around the world ever since. It has even been featured in a pop song and had a cameo in the movie "Deadpool."

For decades, Zambonis have driven down residential streets in Paramount to be tested at Paramount Iceland, a rink that Zamboni, his brother Lawrence and a cousin built in 1939.

College and professional hockey trace their California and LA roots back almost a century. The state's first professional hockey league began in the mid-1920s with the start of the California Hockey League. The minor professional league featured teams including the Los Angeles Richfields, Hollywood Millionaires, Oakland Sheiks, Los Angeles Maroons and San Francisco Tigers. It operated for roughly half a decade, losing and gaining teams yearly.

The Los Angeles Monarchs, a minor professional team, competed in various forms in the first half of the 20th century. They are credited with becoming Los Angeles' first professional hockey champions, when they won the Pacific Coast Hockey League in 1947.

After the Monarchs folded in 1950, professional hockey would not return to LA until 1961, when the Los Angeles Blades began play. The Blades existed until 1967, playing in the Western Hockey league. The team had six relatively unsuccessful seasons, only making the playoffs twice during their lifetime.

The Blades did, however, have major historical significance. Their roster featured the man who had broken the NHL's color barrier, Willie O'Ree. O'Ree was a top scorer for the Blades for each of the team's six seasons.

Early College Powerhouses

During the tumultuous times of early professional hockey in Southern California, amateur hockey was also making inroads. The University of Southern California organized its first club hockey team in 1925, facing club teams from other schools like Loyola Marymount and UCLA in Los Angeles and UC Berkeley in Northern California.

USC and other colleges elevated their club teams to intercollegiate status between 1929 and 1941. During that period, the Trojans and Loyola Marymount had a bitter rivalry that once drew 8,000 fans to a game, described by Sports Illustrated in a 1987 article.

USC had two perfect seasons and a 31-game winning streak, beating Big Ten Champion Minnesota four times in 1938 and 1939. Loyola star John Polich even went on to play for the NHL's New York Rangers.

Southern California hockey at the intercollegiate level fizzled out a couple of years later, after the 1940-41 season, and remained just a distant memory when Sports Illustrated caught up with Arnold Eddy, USC's coach throughout that early run, in 1987. "It's just a lost cause in this climate," he told the magazine.

The tradition of club college hockey continues today, but no Los Angeles-area university fields an intercollegiate-level team.

Royal Return and Mighty Triumph

The NHL made its debut in Southern California when Jack Kent Cooke, who already owned the Los Angeles Lakers of the National Basketball Association, was granted an expansion franchise to establish the Los Angeles Kings in 1966.

The Kings, who played their first game in October 1967, had moderate success throughout their first two decades of existence and featured star players like Marcel Dionne, Dave Taylor and Rogie Vachon.

Even before they snagged Wayne Gretzky, the Kings had a signature moment that helped cement their place in LA sports.

Los Angeles faced the talented Edmonton Oilers and their star player, Gretzky, in the opening round of the 1981-82 Stanley Cup playoffs. With the series tied at one game apiece and the Oilers leading 5-0 in the third period in Los Angeles, the Kings mounted a five-goal comeback. They would win 6-5 in overtime on a goal from Daryl Evans. Fans dubbed the comeback "The Miracle on Manchester" after the street where the Forum, the Kings' arena at the time, is located.

Evans recalled that Angelenos in that era, even if they weren't native, loved hockey.

"I think we had a small nucleus of fans, a very passionate group of fans, and probably a lot of them are still with us today, but it was a limited group," he said. "A lot of transplanted Canadians, East Coast people, but they really liked the game."

Once Gretzky came, the sport exploded: "It was immediate. The minute Wayne came, you'd see the 99 jerseys all over the place," Evans said, referring to his old teammate's uniform number which has been retired by every team in the league. "Without Gretzky, I don't think it would've happened."

Evans' firsthand experience says a lot, but the numbers themselves are staggering. Participation in California, as measured by USA Hockey, grew 221 percent between 1990, two years after Gretzky joined the Kings, and 1996, the year he was traded to the St. Louis Blues. That time period includes the Kings' most successful season with Gretzky on the roster when they lost to the Montreal Canadians in the 1993 Stanley Cup Final.

Luc Robitaille, the Kings franchise leader in goals and a mainstay of the Kings before, during and after the Gretzky years, noticed the growth in another significant way. "Within four years," he told Vice Sports, "there were 10 to 12 rinks that were built."

Gretzky has had a lasting impact on Los Angeles. There are now a number of California natives born during the Gretzky era who play in the NHL. Veteran players Kevan Miller, Matt Nieto and Beau Bennett were born in LA County.

Some argue that Gretzky's influence, though crucial in Los Angeles, did not reach farther south. Gabby Wanchek, who coaches hockey clinics at the Toyota Sports Center in El Segundo, grew up in Orange County, remembers the area as a dead zone for hockey even while Gretzky was in LA.

"At that point, the Kings were here. Some people knew who they were, but there was no coverage on television. There was nothing," she said.

That changed in 1993 when Walt Disney Co. was awarded a franchise to expand the NHL into Anaheim. The company would name the team the Mighty Ducks after the youth team in the 1992 Disney movie of the same name.

Wanchek said people were skeptical at first: "It was like, 'Oh God, what is this? What are they doing?' To try to make the actual sports team off a movie. What is this junk?" But the team did have an impact. "All of a sudden, people were getting interested," she said.

With the combined power of the Ducks' arrival and Gretzky's dominance with the Kings, California's participation in ice hockey ballooned from 4,483 in 1990-91 to 17,355 in 1999-2000, according to USA Hockey.